Exhibit

Creation Date

1839

Height

9cm

Width

6cm

Medium

Genre

Description

In his A Dictionary of Arts, Manufactures, and Mines, Andrew Ure provides a lengthy explanation for the mechanical workings displayed in this simple line-drawing. He begins by describing its basic movements:

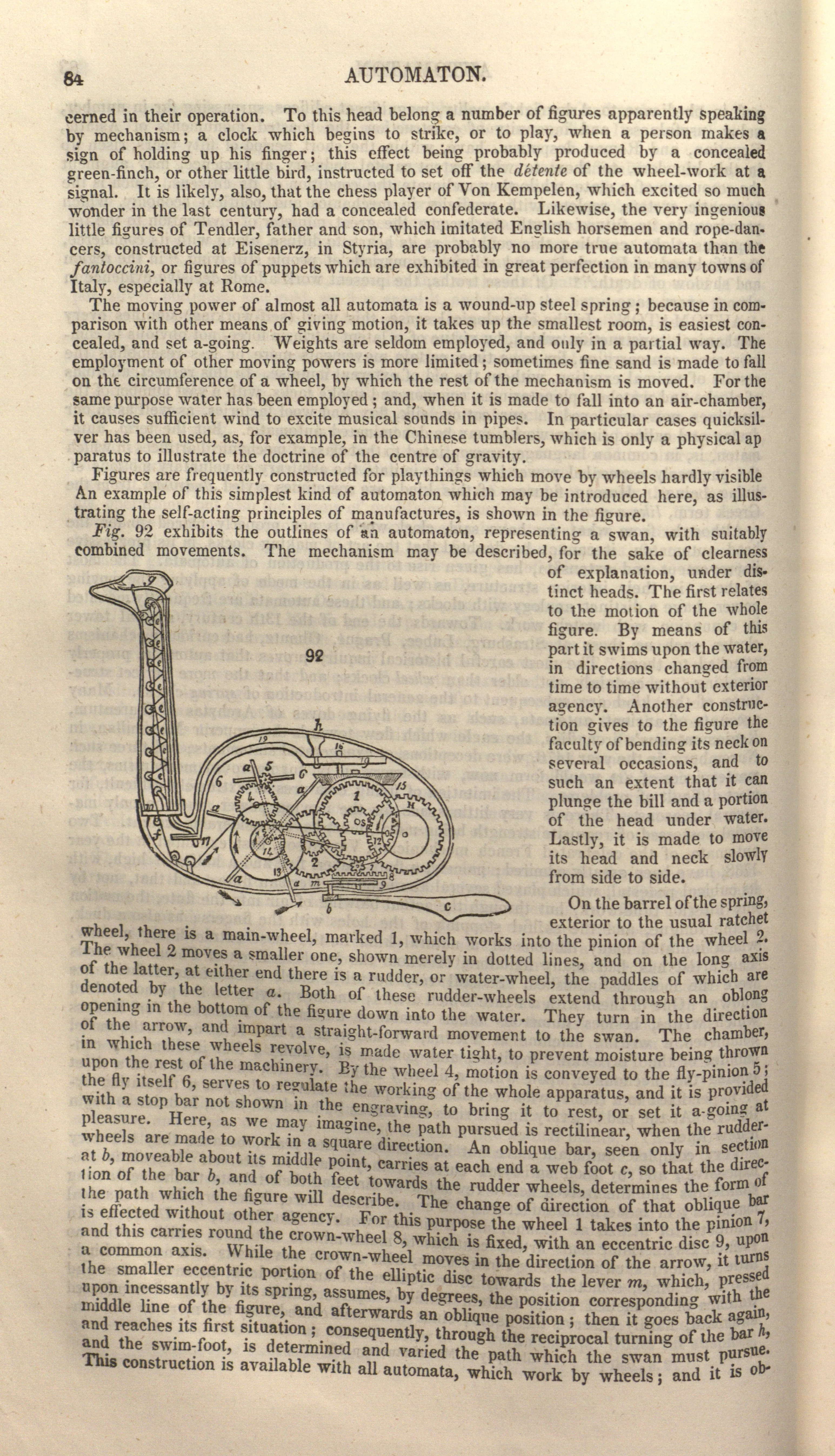

Fig. 92 exhibits the outlines of an automaton, representing a swan, with suitably combined movements. The mechanism may be described, for the sake of clearness of explanation, under distinct heads. The first relates to the motion of the whole figure. By means of this part it swims upon the water, in directions changed from time to time without exterior agency. Another construction gives to the figure the faculty of bending its neck on several occasions, and to such an extent that it can plunge the bill and a portion of the head under water. Lastly, it is made to move its head and neck slowly from side to side. (84)

The inside of the swan’s body is depicted as a series of interlocking and carefully numbered and lettered gears. Behind the duck extends a rudder, which helps it to swim. The neck, “the part which requires the most careful workmanship,” is shown as a series of interlinked triangles representing a steel spring (85).

This image is taken from the entry "Automaton" in Andrew Ure’s A Dictionary of Arts, Manufactures, and Mines (11th ed., 1847). It includes an illustration of an automaton swan, accompanied by an explanation of its mechanism.

There were several iterations of automaton swimming birds from the early eighteenth century to the nineteenth century. The three that have the most bearing on Ure’s version and this gallery are Maillard’s artificial swan (1733), Vaucauson’s duck (1738), and Cox’s silver swan (1773).

Maillard’s 1733 swan seems to most closely resemble the swan that Ure describes in its movements and mechanism. It is characteristic of early eighteenth century automata in that “[i]t was intended to represent the behavior of a natural swan, but by no means to reproduce its physiology” (Riskin, “The Defecating Duck” 602).

Jacques Vaucauson’s 1738 duck added another mimetic dimension to the automaton water bird, swallowing corn and grain pellets and then appearing to digest and expel them. The “defecating duck’s” central mechanism was a fraud—the duck did not actually digest the food, which remained at the base of its neck, but expelled fake excrement from a separate compartment. However, “this central fraud was surrounded by plenty of genuine imitation” (Riskin, "The Defecating Duck" 609). Unlike Maillard’s swan, Vaucauson’s duck was designed to simulate not only movement but physiology, and “[e]ach wing contained over four hundred articulated pieces, imitating every bump on every bone of a natural wing” (609). Andrew Ure mentions the duck in passing, but apparently without realizing its central fraud (for which he vehemently criticizes Kempelen’s chess player) (Ure 83).

James Cox’s silver swan, one of the masterpieces of Cox’s Museum, represents yet another reconception of the automaton bird. His swan also unites genuine mechanical movement with illusionary effects, but Cox foregrounds spectacle and luxurious material rather than mechanical ingenuity or accurate simulation. The swan “swam” along a surface made of glass rods, preened its feathers, moved its head, and caught wriggling silver fish from its pond, which it appeared to swallow (Greater London Council 126). (For more information on Cox and the Museum, see Mr. Cox's Perpetual Motion, A Prize in the Museum Library in this gallery.)

Andrew Ure’s The Philosophy of Manufactures (1835) is Ure’s most famous work and echoes many of the sentiments expressed in the Dictionary, including the entry "Automaton.” Ure’s work contributed to “a new literary genre” in the 1830s of “factory guide books,” and takes as its focus the cotton industry (Edwards 17). As Edwards makes clear, the book’s “fantasy of labour helped shape the industrial series and its inverse—the socialist imaginary,” as it was interpreted and read by Marx in Das Kapital (17).

Andrew Ure’s version of the history and value of automata is significant for the narrative of progress it constructs. The detail with which he describes the swan automaton shows both the complexities of these objects and Ure’s own fascination with their mechanism. The first lines of his dictionary entry, which move from animal automata and clocks to wool factories and calico printing, also make clear his capitalist enthusiasms:

In the etymological sense, this word (self-working) signifies every mechanical construction which, by virtue of a latent intrinsic force, not obvious to common eyes, can carry on, for some time, certain movements more or less resembling the results of animal exertion, without the aid of external impulse. In this respect, all kinds of clocks and watches, planetariums, common and smoke jacks, with a vast number of the machines now employed in our cotton, silk, flax, and wool factories, as well as in our dyeing and calico printing works, may be denominated automatic. (83)

As he soon emphasizes, this list is not a catalogue but a progression, and one that is traced throughout the Dictionary: “Very complete automata have not been made of late years, because they are very expensive; and by soon satisfying curiosity, they cease to interest. Ingenious mechanicians find themselves better rewarded by directing their talents to the self-acting machinery of modern manufactures” (83).

Ure may have had in mind Jacques de Vaucauson, who went on to invent an automatic loom that created a backlash among French weavers. As Botting observes,

[t]he move from mere entertainment to threat is explicit in Jacques de Vaucanson’s work: the inventor of the clockwork duck that simulated excretion responded to the hostility of the silk workers whose livelihood was threatened by his construction of an automatic loom by making another machine, this time operated by a donkey. (Botting, para. 17; see also Riskin, “The Defecating Duck” 624-29)

However, automata continued to be produced in abundance throughout the nineteenth century and cannot be seen solely as a stepping stone in the history of industrialization. Similarly, automata makers throughout the period often engineered and built mechanisms for diverse purposes—from luxury goods (Cox) and phantasmagoric spectacles (Maelzel) to medical apparatuses (Merlin, Adams), scientific investigations (Vaucauson, Kempelen), and industrial technologies (Vaucauson). The rhetoric of Ure’s text makes apparent the complex intersections of technology, mimesis, and labor in the Romantic period.

Associated Works

Copyright

Copyright 2009, Department of Special Collections, Memorial Library, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI

Collection

Accession Number

Cole Coll C 997

Additional Information

Bibliography

Altick, Richard. The Shows of London. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard UP Belknap P, 1978. Print.

Botting, Fred. “Reading Machines.” Gothic Technologies: Visuality in the Romantic Era. Ed. Orrin N.C. Wang. Romantic Circles Praxis Series. December 2005. Web. 26 January 2009.

Edwards, Steve. “Factory and Fantasy in Andrew Ure.” Journal of Design History 14.1 (2001): 17-33. Print.

Farrar, W. V. “Andrew Ure, F.R.S. and the Philosophy of Manufactures.” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 27.2 (1973): 299-324. Print.

Greater London Council Public Relations Branch. John Joseph Merlin: The Ingenious Mechanick. London: Greater London Council, 1985. Print.

Landes, Joan. “The Anatomy of Artificial Life: An Eighteenth-Century Perspective.” Riskin 96-116.

Miles, Robert. “Gothic Romance as Visual Technology.” Introduction. Gothic Technologies: Visuality in the Romantic Era. Ed. Orrin N.C. Wang. Romantic Circles Praxis Series. December 2005. Web. 19 January 2009.

Riskin, Jessica. “Eighteenth-Century Wetware.” Representations 83 (2003): 97-125. Print.

---, ed. Genesis Redux: Essays in the History and Philosophy of Artificial Life. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2007. Print.

---. “The Defecating Duck, or, the Ambiguous Origins of Artificial Life.” Critical Inquiry 29.4 (2003): 599-633. Print.

Ure, Andrew. "Automaton." A Dictionary of Arts, Manufactures, and Mines: Containing a Clear Exposition of their Principles and Practice. 11th ed. New York, 1847. Print.

Wise, M. Norton. “The Gender of Automata in Victorian Britain.” Riskin 163-195.