Exhibit

Creation Date

1817

Height

19 cm

Width

12 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

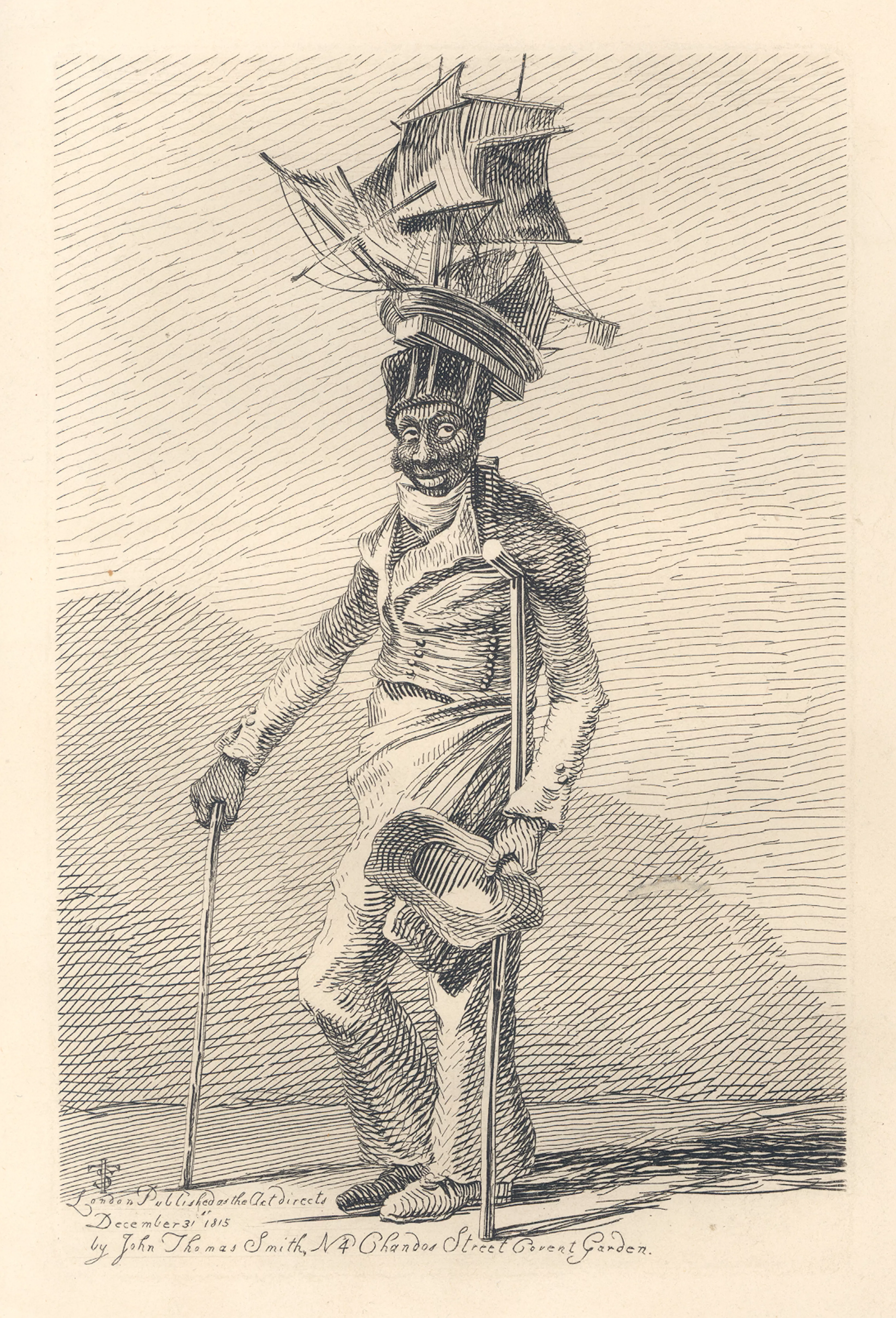

This image features Joseph Johnson, a beggar and street singer, wearing a model of the HMS Nelson he built himself as a hat.

A black man in a sailor’s uniform leans on a crutch and cane in a nondescript environment. In his left hand he holds a brimmed hat, while atop his head sits an elaborate model ship affixed to a simple cylindrical cap.

Vagabondiana strives to classify London’s myriad and diverse population of wandering poor into distinct categories. Organized around abstract qualities such as industriousness, the text produces an archive of distinct “types” valued for their perceived role as representative of larger categories. “Black Joe” is taken to represent both the black urban poor (he is one of only two characters in the book identified by a racial signifier) and the particularly creative or ingenious beggar.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, London had a sizable black population ranging from between 15,000 to 20,000 residents, more than half of whom were free (Olsen 29). Working as a sailor was one of many, primarily lower-class occupations available to black Britons. Joseph Johnson is notably excluded from the military and thus, despite obvious injuries, does not receive compensation from Greenwich. Johnson’s choice of hat may have been inspired by his time as a sailor, and yet the juxtaposition of a black man and large ship during a time of heated debate surrounding slavery also resonates on other levels. At the time of this sketch, “taken from life,” the slave trade had (ostensibly) been abolished, but slavery itself was still rampant—a fact that may or may not have been lost on the women taking sugar in their tea as Johnson theatrically “sailed” passed, “by a bow of thanks, or a supplicating inclination to a drawing room window” (Smith 33). Additionally, ships held the threat of deportation, as London officials concocted solutions to the “problem” of the city’s black poor. Proposals to rid the city of black beggars included a plan put forth by Henry Smeathman in 1786 to ship London’s impoverished blacks to Sierra Leone, where they could become self-sufficient and eventually begin to “supply Britain with various raw materials” (Gerzina 142-73).

The treatment of beggars, vagabonds, and the disabled was one issue around which the English constructed their identity, especially in attempting to distance themselves from the French. It is telling that the concluding remarks of Smith’s text are taken from a community “deprived of its property during the French Revolution.” By alluding to the atrocities of the Revolution, the audience is reminded of the dangers of not “appeasing” the poor through charitable acts in the “English manner.” While the unemployed (or seemingly unemployed) were often considered a problem or nuisance, they were also admired for their creativity and theatrics (it is worth noting that traveling players were among those consistently classified as vagrants). “Black Joe’s” inventive strategy is lauded, though the author admits that in highlighting such examples “he has adopted the usual craft of the common vender, who invariably puts the best sample into the mouth of the sack” (Smith viii). The recognizability of a particular vagrant could also foster national coherence. We are told that “Black Joe” can traverse many towns in a single day, and thus, although he cannot be claimed by any one parish, he becomes a known personality shared by many dispersed communities.

The mobility of the homeless also served the Romantic artistic imagination in a number of ways. First, for poets and painters, the rural and urban poor were popular subjects, either as models, objects of meditation or catalysts for expressions of empathy, longing, and admiration. Furthermore, as the introduction to Vagabondiana reminds us, “Beggars have not only been useful to artists as models, but serviceable to them in other instances. Francis Perrier, who was born of poor parents, when a boy, entered in to the service of a blind beggar, for the express purpose of getting from France to Rome, to pursue his studies in that city; and Old Scheemaker, the sculptor, Noleken’s master, absolutely begged his way from Flanders to Rome, for the same purpose” (Smith viii). Thus, the wandering lifestyle of beggars and vagrants was often seen as compatible with an artistic interest in new and varied experience gained through unrestrained travel.

Locations Description

Chandos Street, Covent Garden, London

Collection

Accession Number

Thordarson T 4263

Additional Information

Bibliography

Gerzina, Gretchen. Black London: Life Before Emancipation. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1995. Print.

Olsen, Kirsten. Daily Life in 18th Century England. Westport: Greenwood, 1999. Print.

Smith, John Thomas. Vagabondiana, or, Anecdontes of Mendicant Wanderers Through the Streets of London. London: A. Arch, 1817. Print.