Exhibit

Creation Date

1870

Height

30 cm

Width

43 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

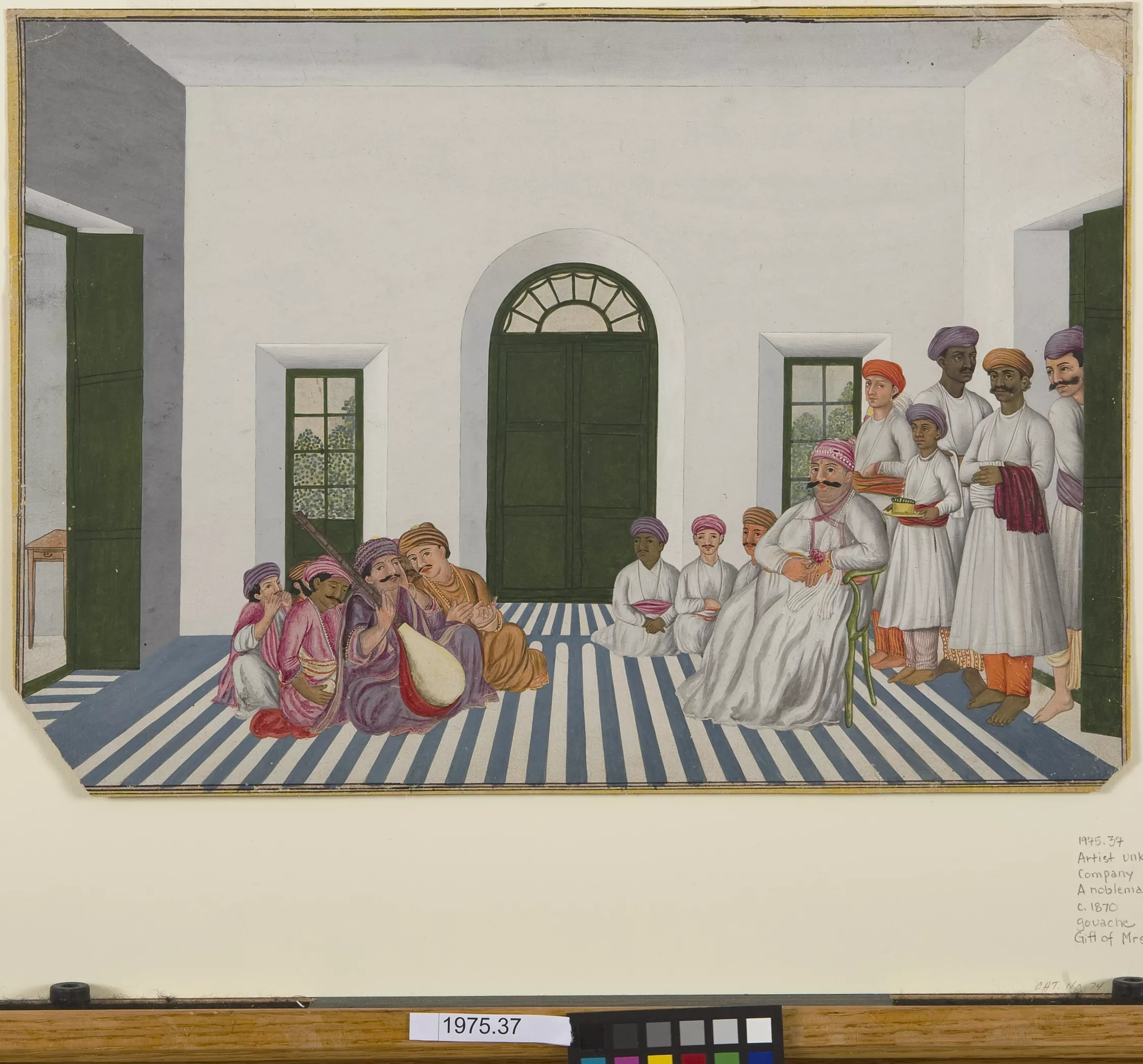

The art historian Pramod Chandra describes this miniature as follows:

[T]he man, seated on a chair, listens to a group of musicians squatting on a striped blue carpet. He is attended by several retainers, one of them about to step out of a door. The walls of the room are plain and painted a bluish white. The clothes of the musicians and the turbans of the nobleman and his retainers provide accents of color. The carefully worked out perspective and the attempts made at modeling the clothes and facial features show a keen desire to imitate western painting. (47)

This image was accomplished in a hybrid, Indo-European style. The subject matter, in which a nobleman is entertained by a retinue of musicians, is a common motif in traditional Mughal paintings of the eighteenth century. One example of this is a Portrait of a Nobleman—executed in 1760 and preserved in the Watson collection—in which a nobleman reclines on a divan, fanned by an attendant and listening to the performance of three female musicians. This type of imagery was also used by a group of British officials that Dalrymple describes as “White Mughals”: Europeans who integrated into Indian culture by adopting traditional clothing, cultural practices, social mannerisms, and by taking Indian wives (bibis) (Dalrymple 143). In a similar painting finished in 1820, Sir David Ochterlony reclines on a low chair, smoking a hookah and surrounded by attendants and entertainers. His traditional Indian dress and position in the painting suggest that he is conducting himself like any "typical" Indian nobleman. The subdued hues, and particularly the predominance of white, are also reminiscent of traditional Mughal imagery. As Vajracharya points out in reference to the Mughal Portrait of a Nobleman, “the color white and other softer palettes dominate the scene, in accordance with the popular color scheme of the eighteenth century” (Vajracharya 85).

The European influence in this image is not, however (as Chandra suggests) the attempt of an Indian artist to render more realistic facial features; rather, "Englishness" is manifested in the interior décor of the nobleman’s home. Instead of lying on divan or a Persian carpet, the nobleman in this image sits in a chair on a striped floor, surrounded by white walls and a door with an arched window. Consequently, this nobleman’s home resembles the interiors of British bungalows in India. These architectural spaces sought to isolate the British from the Other and create visual boundaries of difference.

By placing an Indian man in a British space, the artist inverts the cultural integration of the “White Mughals,” reversing the absorption of "Englishness" into Indian society. This interpretation unsettles the idea that Indian artists are slavishly imitating Western art; rather, in its mixed selection of styles, settings, and persons, the subtly-distorted mimesis of the work may be a covert means of claiming agency.

During the time this image was created, Britain established a centralized government in India. Because it is unknown who the artist was and where he was located during the execution of the work, it is unclear what types of cultural interactions may have occurred between the artist and his patron. Mildred Archer states that Company paintings were made for and marketed to European patrons that were employed by the East India Company (Archer 1-19). However, sultans and princes under British rule may also have been patrons of Company-style paintings, as many Indian princes and rajahs in the late eighteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries were patrons and collectors of European art (Sutton 15-17). This trans-cultural contact through the exchange of art had an early precedent in the reigns of the Mughal rulers. One of the earliest recorded accounts occurred in 1580, when Akbar (r. 1556-1605) invited Portuguese Jesuits living in Goa to stay at his palace in Delhi. The exchange of engravings, manuscripts, and books led to the production of a panoply of Christian images that adorned Akbar’s court (Bailey 24-5).

The visual classification of "types" of Indian people is a consistent motif in Company style paintings. This gallery includes several examples of such paintings: The Painter at Work, The Indian Fruit Seller, The Bangle Maker, and The Nobleman Listening to Music. A large collection of Company paintings that depict various types of people—from “The potter firing pots on a small kiln,” to “A man block-printing on cloth,” to a “Prostitute reclining on a couch”—are housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum and in the India Office Library in London (Archer 106).

A Nobleman Listening to Music depicts a "typical" Indian nobleman, in full Muslim attire, sitting at home while being entertained by a small group of musicians. The stark interior of his dwelling can be contrasted with the brightly-colored, ornate homes of most Indian noblemen (see the image of Raja Jagat Prakash in this gallery). The hybrid style evident in this image is an example of the trasculturation occuring during the Romantic period as Indian artists were exposed to the English aesthetic through art and architecture. This depiction of a nobleman can be contrasted with another image from this gallery, A Painter at Work, which attempts to classify the “artist type” through the lens of the caste system. Conversely, the artist of A Nobleman Listening to Music frees his subject from the strict adherences of social status by casting him in the role of an Englishman.

Accession Number

1975.37

Additional Information

Bibliography

Archer, Mildred. Company Paintings: Indian Paintings of the British Period. London: Victoria and Albert Museum in association with Mapin Publishing, 1992. Print.

Bailey, Alexander Gauvin. “The Indian Conquest of Catholic Art.” Art Journal 57.1 (1998): 24-30. Print.

Chandra, Moti. The Technique of Mughal Painting. Lucknow: U. P. Historical Society, 1949. Print.

Chandra, Pramod. Indian Miniature Painting; the Collection of Earnest C. and Jane Werner Watson. Madison: Elvehjem Art Center, University of Wisconsin; distributed by U of Wisconsin P, 1971. Print.

Dalrymple, William. White Mughals: Love and Betrayal in Eighteenth-Century India. New York: Viking, 2003. Print.

Sutton, Thomas. The Daniells; Artists and Travellers. London: Bodley Head, 1954. Print.

Vajrā cā rya, Gautamavajra. Watson Collection of Indian Miniatures at the Elvehjem Museum of Art: A Detailed Study of Selected Works. Madison: Elvehjem Museum of Art, 2002. Print.