Creation Date

1811

Height

17 cm

Width

25 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

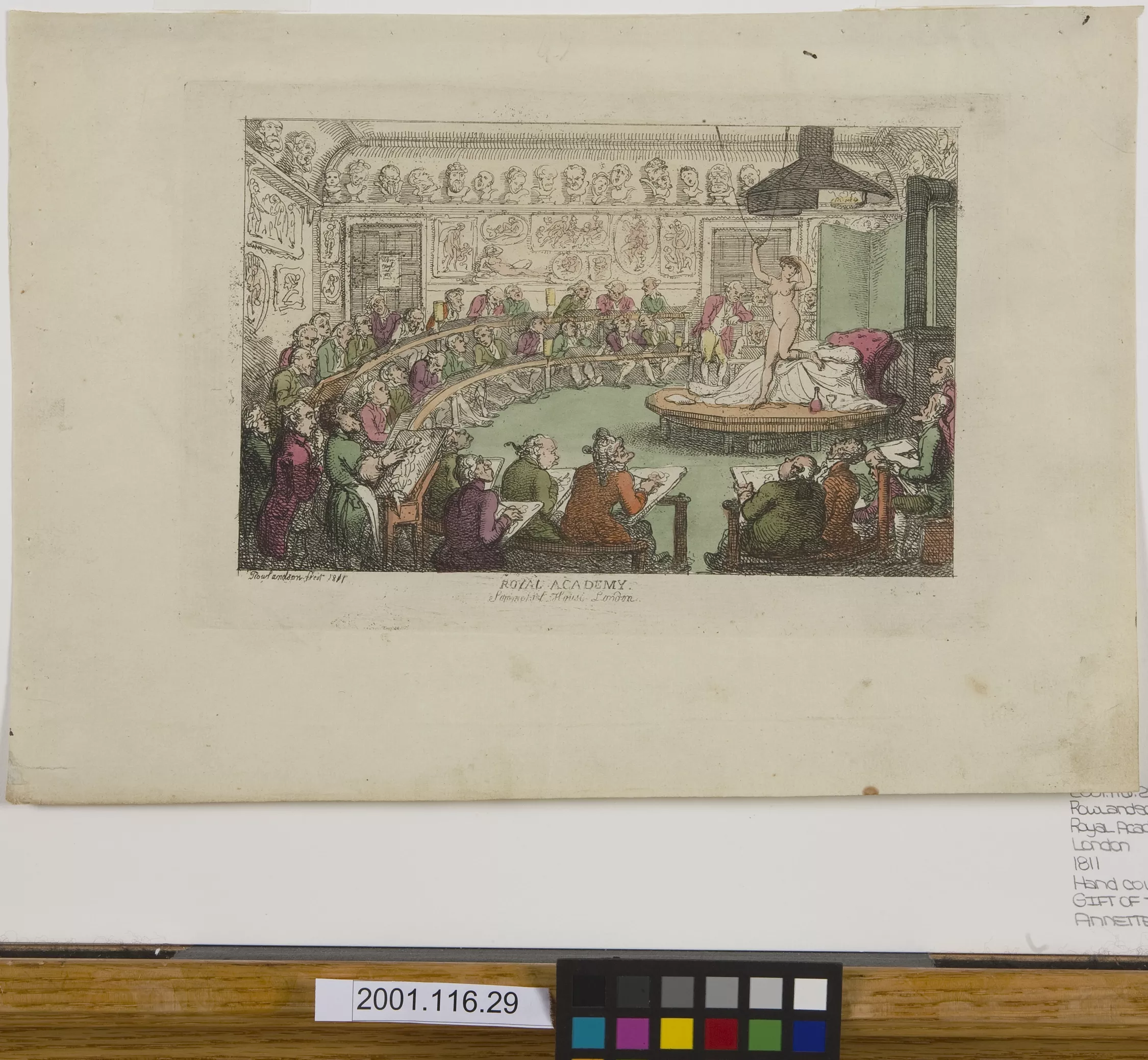

In this image, students of the Royal Academy at Somerset House are trained in the techniques of observing and depicting the female nude.

The artists of the Royal Academy sit in a semicircle, in two tiers, with sketch pads and pencils, facing a female model posing nude on a stage. Most of the men look at the model, while others draw or converse; some appear bored or asleep, their heads nodding and eyes shut. A few wear spectacles. A man in a pink coat and yellow breeches stands to the left of the model, leaning on a desk. The brown-haired model, nude, stands with her left leg bent up behind her to rest on a red couch draped with white cloth, her left hand on her head, and her right hand resting on a suspended cord. She stands, illumined by a light, beneath a hood and flue. Next to the couch is a carafe of wine and an empty glass. Along the walls of the room hang paintings and sketches, most of them featuring nudes; busts line the ledges mounted high on both walls. The walls and artwork are white, contrasting with the green carpet and the green, red, purple, and orange coats of the artists.

Rowlandson grants the viewer access to the living model through his Royal Academy – Somerset House. The objective of the life drawing class was to train the artist in the observation and depiction of the nude. Although female models were used frequently, the representation of life drawing classes using female nudes is more rare than the depiction of classes with male nudes; see, for example, Zoffany’s celebrated The Academicians of the Royal Society. Even Rowlandson’s illustration for Ackermann’s The Microcosm of London (1808-10), which is closely related to Royal Academy – Somerset House in form and content, presents readers and viewers with the significant replacement of the female with the male nude.

The female model is the main focal point of the print for the viewer as well as the center of attention for the clothed men in the life drawing class. The gaze set upon her is a solely male one: there are no women artists in the print, and women were not allowed as students in the life drawing classes (this is significantly depicted by Zoffany, who relegates the only two women Academicians, Mary Moser and Angelica Kauffman, to portraits on the wall). This exposure of the female nude to the male aesthetic gaze participates in the appropriation and the containment of the female body:

The representation of the female body within the forms and frames of high art is a metaphor for the value and significance of art generally. It symbolizes the transformation of the base matter of nature into the elevated forms of culture and the spirit. The female nude can thus be understood as a means of containing femininity and female sexuality. (Nead 2)

The artists examine and probe her body with a gaze that is at once academic and erotic; this gaze, distinctly male, attempts to contain the female body, translating the female subject into a static nude through the aestheticizing and commodifying practices of the hand—through pencil and sketches.

However, the female model’s extremely exposed posture also seems to enable her to resist containment. She is shown explicitly in a very revealing pose, with her hands raised, rather than in a Venus pudica posture. In contrast, Rowlandson’s Drawing from Life depicts a nude male model, in a Rodin’s Thinker pose, turned away from the viewer. Though the female model here is posed by the instructor of the life drawing class, the model in her extravagant nudity is accorded a sense of agency beyond her aesthetic subjection. Lynda Nead argues that the “female nude not only proposes particular definitions of the female body, but also sets in place specific norms of viewing and viewers” (2). In this case, the female nude suggests and prompts alternative viewing practices: there are men who studiously examine her, but there are also men who look at each other in conversation, some who look bored, and several who seem to be sleeping. With a portion of the male gaze diverted and averted, there is room for the model to perform her own share of looking: her line of sight, though contained by her pose, is directed at a male artist. Thus, the female model exemplifies Nead’s “female body as representation, with woman playing out the roles of both viewed object and viewing subject, forming and judging her image against cultural ideals and exercising a fearsome self-regulation" (10).

The viewer is implicated in this web of viewing representation through the opening of the semicircle and the break in the tier which positions and thereby includes the viewer in the life drawing class. Though the viewer begins on the side of the male artists—clothed and gazing at her nude form—he eventually moves to that of the female model, turning the gaze back on the male spectators. Consequently, Rowlandson’s depiction of the life drawing class enables the viewer to train his or her aesthetic eye in the observation of the nude and of art in general.

Locations Description

The Royal Academy was founded in December, 1768, with the support of George III. Though private academies, auction houses, art clubs, and print shops had been prevalent in London for a century, access to art remained limited. The Royal Academy began to address this problem by functioning as a public center of the arts, providing education and access to art through its school and annual exhibitions. It was also considered the major force behind the professionalization of art; this was due in large part to the Royal Academy Schools, where the distinction between the liberal arts—painting, sculpture, and architecture—and the mechanical arts—such as engraving and craft-oriented practices—turned on education (Bermingham 130).

Though the Academy was one of the last academies to be founded in Europe, it was the first truly modern institution, and was run independently by its artist members. Free of government support and patronage, it supported itself through annual exhibitions. The Royal Academy not only served as a school of learning and a major site of art exhibitions, but also acted as a charity for the relief of poor artists and their families. Its membership consisted of forty Royal Academicians and numerous associates. Artists included painters, sculptors, architects, and, eventually, engravers. The Academy held the foremost position as the arbiter of taste until the nineteenth century (Schofield).

Despite these modern innovations, female membership in the Royal Academy was very limited. At its founding, there were only two women Academicians, Mary Moser and Angelica Kaufmann. Upon Moser’s death and Kaufmann’s return to the Continent, women were not admitted to the Academy until Annie Swynnterton acquired membership in 1922 (Fenton 252).

The Royal Academy Schools made up the most important institution of art education in London until the establishment in 1837 of the Government School of Design (Hoock 52). Following the Renaissance tradition of art training—centered around the antique, the life class, and the study of anatomy—the Royal Academy Schools, under the direction of the Keeper, were made up of the Antique Academy, the Plaster Academy, and the Academy of Living Models; the Painting School was added in 1815 when permission was obtained to borrow pictures from the Dulwich Picture Gallery (Nead 46). As can be concluded from these divisions, the human figure constituted the principal area of study.

Students underwent a probationary period before being formally accepted to the Schools. The order of coursework for those accepted mandated at least one term at the Antique Academy before attendance at the Life Academy. The Academy Schools’ studentship initially lasted six years, but was later extended—first to seven, and then to ten years; consequently, not many students completed the course. Women, though not barred, were not admitted to the Royal Academy Schools until 1860, and then only on a small scale; furthermore, they were not allowed entry to the Life Academy (Hoock 53). Teachers were drawn from the Academicians and Associates and taught for several months at a time. Education was free until 1977. Prizes were given annually, presented with a discourse given by the President; these ceremonies resulted in Sir Joshua Reynolds’ fifteen discourses, which served as the Academy’s policy for the arts (Schofield).

The Life Academy used both male and female models. Though men were able to model as a form of casual employment, women models were employed anonymously (some female models were actually prostitutes) (Fenton 131, 146-47). However, in contrast to schools on the Continent, English academies from the late seventeenth century onwards used female models fairly frequently (Nead 46). Interestingly, the importance of the female model is shown in the change in rates of pay. At the start of the Academy, they were paid half a guinea—ten shillings and sixpence—a night, while male models were paid three shillings; in 1811, the women’s rate was twelve shillings to the men’s five, and by 1821 the rates were (respectively) one guinea to half a guinea (Fenton 131).

Located on the south side of the Strand on the banks of the Thames in central London, Somerset House functioned first as an aristocratic mansion, then as a royal estate, until 1649, when it fell into disuse. In the 1660s, it was rebuilt according to the designs of the late architect Inigo Jones (1573-1652), only to be demolished a century later in 1775. The Royal Academy was permanently housed in the new Somerset House, designed by William Chambers, from 1780 until 1836, when it moved to the National Gallery. Previously the Academy had been meeting in auction rooms in Pall Mall, which were hired season by season. The move to Somerset House was symbolic in establishing the Academy as a prestigious institution: by housing the Academy in the same residence as the Royal Society, the Society of Antiquaries, and the Royal Navy, art and the Academy acquired state significance (Fenton 114-15). The Royal Academy spaces at Somerset House constituted its school, library and collection of casts and galleries: the Life Academy was located on the ground floor; the Antique Academy, in the library; the Council Room, on the first floor; and the Great Room, on the top floor (Solkin xi; Murdoch 17).

Accession Number

2001.116.29

Additional Information

Bibliography

Bates, L.M. Somerset House: Four Hundred Years of History. London: Muller, 1967. Print.

Bermingham, Ann. Learning to Draw: Studies in the Cultural History of a Polite and Useful Art. New Haven: Yale UP, 2000. Print.

Fenton, James. School of Genius: A History of the Royal Academy of Arts. London: Salamander Press for the Royal Academy of Arts, 2006. Print.

Grego, Joseph. Rowlandson the Caricaturist: A Selection from His Words, with Anecdotal Descriptions of his Famous Caricatures and a Sketch of his Life, Times, and Contemporaries. London, 1880. Print.

Hayes, John. “Rowlandson, Thomas (1757-1827).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. Lawrence Goldman. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Web. 1 July 2013.

Hoock, Holger. The King’s Artists: The Royal Academy and the Politics of British Culture 1760-1840. Oxford: Clarendon, 2003. Print.

Murdoch, John. “Architecture and Experience: The Visitor and the Spaces of Somerset House, 1780-1796.” Art on the Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House. Ed. David Solkin. New Haven: Yale UP, 2001. 9-22. Print. Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

Nead, Lynda. The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity and Sexuality. London: Routledge, 1992. Print.

Paulson, Ronald. Rowlandson: A New Interpretation. London: Studio Vista, 1972. Print.

Pyne, W.H. and William Combe. Microcosm of London, or London in Miniature. 3 vols. London: Ackermann, 1904. Print.

Schofield, John, et al. “London.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford UP. 18 Jan. 2006. Web. 1 July 2013.

Solkin, David, ed. Art on the Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House. New Haven: Yale UP, 2001. Print. Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.