Exhibit

Creation Date

1819

Height

25 cm

Width

15 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

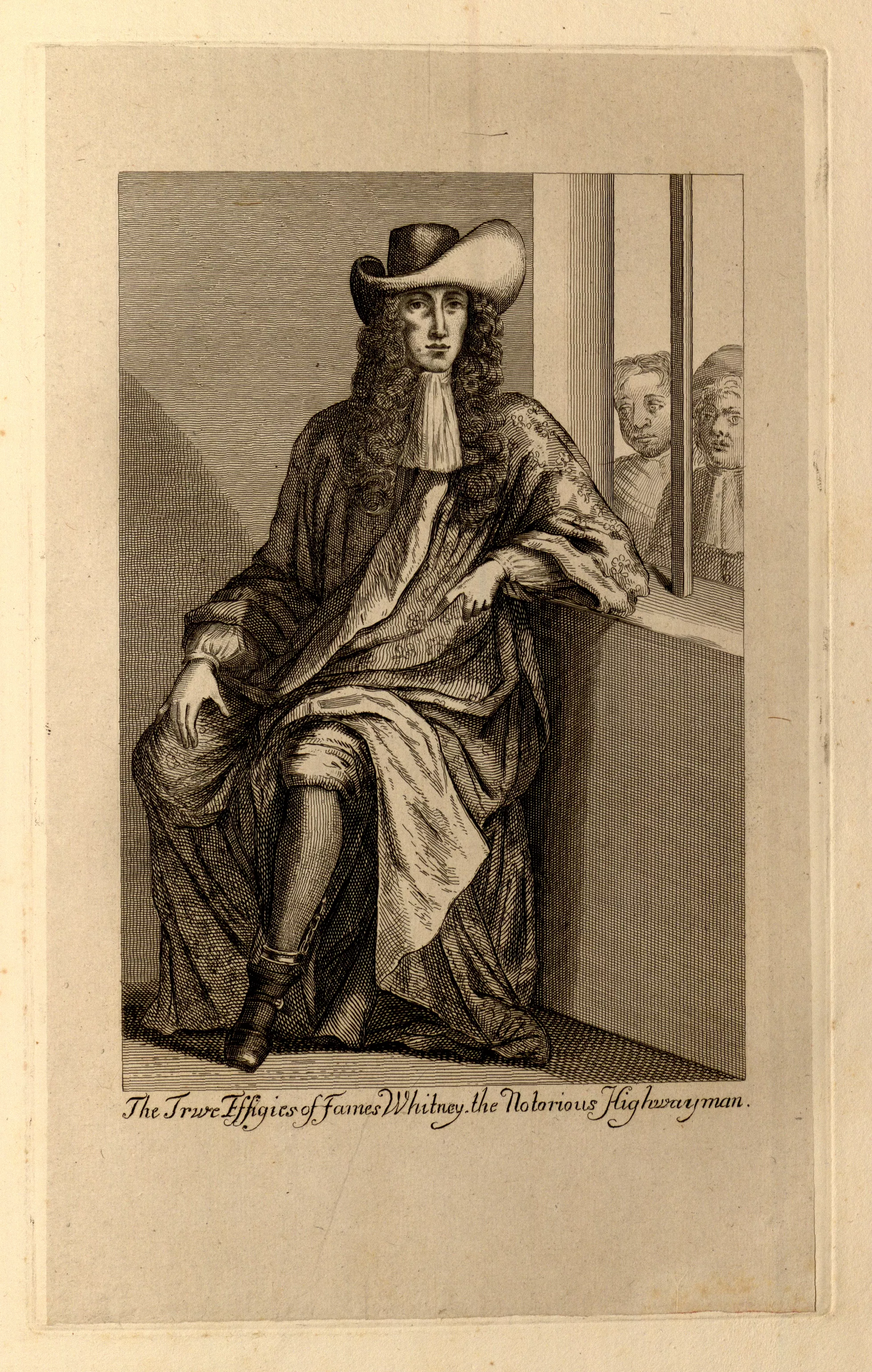

A man, imprisoned, sits in the corner of a cell next to a barred window through which two figures stare. The captive wears a large brimmed hat, long curled wig, and cravat, which date the sitter to the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century. He wears a loose, patterned gown, which is lifted to reveal a stockinged leg with a shackle and chain at the booted ankle. The man looks at the viewer and points with his left hand to his exposed and shackled leg.

Despite his status as a vagabond and criminal, Whitney (following the conventions of late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century portraiture) is shown in the dressing gown of an artist-gentleman. This unusual citation speaks to the conflation of artistic and wandering types in the Romantic period.

Whitney is shown is clothing appropriate to the period in which he was captured (1694). His long periwig, crimped linen cravat, and flamboyant hat make him immediately recognizable as a historic figure, and signal his status as a “gentleman thief” (Caulfield 64). The bared window and prominent shackle, to which Whitney draws our attention by pulling back his gown and pointing with his left hand, emphasize his captive status, though his elaborate dress and the retention of his hat suggest that he is newly caught. The long, patterned dressing gown, in addition to marking Whitney as a historic figure, also constructs him as gentleman-artist. The gown was a well-established convention for portraits of artists, men of letters, and musicians in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, employed for its “timelessness” and desirable affinity to classical drapery (Ribeiro 90, 102). More specifically, the dressing gown signified the gentlemen scholar or artist who worked at home, and who was thus able to don an informal robe, which could be easily replaced with a waistcoat and coat if visitors called (Cummings 130).

The dressing gown is a strikingly odd choice for the portrait of a roaming criminal who was emphatically disassociated from the domesticity such an article connotes. The tension between the interior leisure of the gentleman-artist and exterior roving of the gentleman-thief is made more pronounced by Whitney’s retention of his hat, which would be necessary for his wandering criminal lifestyle, but unnecessary for the man of letters depicted in his study. In fact, gentlemen are almost never painted wearing a hat in formal portraiture of the period, though they often hold a chapeau under the arm or in hand. The decision to dress Whitney as a gentleman-artist type could thus be seen as one way in which the Romantic artistic persona was conflated with that of the vagabond. In support of this reading, we find that in the accompanying narrative it is not his villainy but his wit, creativity, and the ingenuity of his artifice that receives the greatest attention.

Encyclopedic volumes of eccentric or notable characters, such as Caulfield's, were produced to entertain and educate, but also worked to establish visual and behavioral categories of normalcy and deviance.

James Whitney lived during the reign of William III (1689-1702). He was executed on the 19th of December, 1694.

Locations Description

James Whitney was born in Stevenage. He was imprisoned in Newgate on December 31, 1692, and tried and convicted at the Old Bailey (Faller). Though initially pardoned on the basis that he had more information to supply regarding a plot to kill the king, Whitney was ultimately executed by hanging near Smithfield, an area in London used as a livestock and meat market, in order to discourage other ambitious or treasonous commoners of the butcher's trade (Faller).

Collection

Accession Number

Thordarson T 510 v. III

Additional Information

Bibliography

Caulfield, James. Portraits, Memories and Character of Remarkable Persons. London: H.R. Young and T.H. Whitely, 1819. Print.

Cummings, Valerie. A Visual History of Costume: The Seventeenth Century. London: Batsford, 1984. Print.

Faller, Lincoln B. “Whitney, James (d. 1693), Highwayman.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Web. 19 June 2013.

McCalman, Iain, et al., eds. The Oxford Companion to The Romantic Age: British Culture 1776-1832. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. Print.

Ribeiro, Aileen. The Gallery of Fashion. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2000. Print.