Creation Date

1792

Height

10 cm

Width

16 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

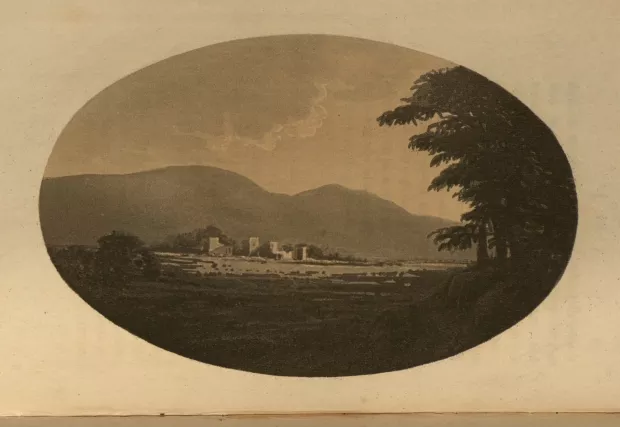

The image depicts a broad, flat plain, interrupted at its further end by a grey body of water. In the distance, a low mountain range looms in vague, dark contours against the sky, nearly touching the cloud formations above. Small, white buildings, dwarfed by the mountains, cluster on the plain between the body of water and the mountain range. What appear to be tall fir trees are grouped darkly in the right quarter of the aquatint. Another tree sits low in the left corner.

The aquatints engraved for Gilpin’s Tours were based on sketches made by Gilpin himself. A comparison of similar aquatints from the second, third and fifth editions reveals subtle variations among them and suggest that new aquatint etchings were used in each printing. Gilpin first toured the Wye area in the summer of 1770 while still master of the boy’s school at Cheam in Surrey. He illustrated an account of these travels which received praise in its unpublished form from both Under Secretary of State, William Frasier, Esq. and the poet, Thomas Gray (Templeman 227). In this image, Welsh ruins blend into the countryside, symbolizing the close connection between medieval architecture and picturesque beauty.

By the 1790s, the British aristocrats who had grown accustomed to visiting the sites of ancient Greece and Italy had been cut off from the Continent by the violent and unstable political situation (Andrews 34). As a result, domestic sites came to constitute a new "Grand Tour." Gilpin highlighted the affordability of travel in England, Wales and Scotland, and argued that such national sites held the potential for enacting moral edification (Bermingham 86). This potential arose in the exposure of the viewer to the divine in nature: "a search after beauty should naturally lead the mind to the great origin of all beauty . . . Nature is but a name for an effect, / Whose cause is God" (Gilpin, Three Essays; 46-7).

The Abergavenny ruins are difficult to identify as ruins in this aquatint. In the accompanying text, Gilpin briefly comments on the castle as if it is only barely noticed: “We approached it [Abergavenny] by the castle; of which nothing remains, but a few staring ruins” (Gilpin 90). The ruins blend into the overgrowth as if it were becoming another land formation, and its towers are echoed and overshadowed by the peaks of the mountain range behind it: the first crest is directly beneath the left peak of the mountain, and the second crest of the ruins mimics the descending gradation of the right mountain peak.

Medieval ruins were valued in the Romantic period because their decaying forms were being subsumed by the landscape—stained, overrun and rent by insects and vegetation (Ruskin qtd. in Lowenthal: 157). Scholars such as Malcolm Andrews and Anne Janowitz argue that, in the attempt to unify the diverse peoples of the British Isles into one nation, ruins became sites of national memory and historic pride, material evidence of a history shared by England, Scotland and Wales (Andrews, Part I; Janowitz 4). Several primary sources support this opinion. A ruined mansion in Brambletye was the occasion for John Byng to contrast his own era to "those Gothic days":

Over and about these ruins I . . . meditated . . . [on] the great improvements of the roads, which have introduced learning and the arts into the country and removed the (formerly wretched) families, who buried themselves in mud and ignorance, to the gay participation of wit and gallantry in the parishes [towns] of Marylebone and St. James! (Byng 89)

Commenting on the ruined Caraig-cennin Castle in Wales, traveler Henry Penruddocke Wyndham declared: "'This was doubtless . . . a British building, as is evident from its plan and the style of its architecture’" (qtd. in Mavor: 343). For Wyndham, then, “Britain” is represented in a Welsh ruin by synecdoche. While Gilpin himself may not have been consciously seeking to express such ideas, his renderings of the ruins nevertheless serve to illustrate the visual unity connecting the British land with its national monuments.

Associated Works

Locations Description

Wye River

The Wye River, one of the major rivers in Britain, runs through Wales and England. North Wales in particular became a popular picturesque tourist destination in the later half of the eighteenth century.

Boldre

One of Gilpin’s former students at Cheam, Colonel William Mitford, heard of his former schoolmaster’s desire to retire from the school at Cheam and offered him a wage in Boldre. Gilpin accepted, and he served as the Vicar of Boldre, Hampshire from 1777 until his death in 1804 (Templeman 148). From the beginning of this appointment until 1791, he kept up his drawing while attending to the affairs of his new parish community. He initiated an association to aid the impoverished in the neighboring town of Lymington and supported the foundation of Sunday and day schools in Boldre (Templeman 186-91). The revenues from sales of his Tours allowed him to establish two schools in Boldre in 1791 (Gilpin: qtd. in Templeman 194). Between 1797 and 1800, a period of prolonged illness, he published another set of sermons and additional accounts of his domestic travels (Observations on the Western Parts of England), as well as working to arrange the the posthumous sale of his works in order to establish an endowment for his schools (Barbier 92; Templeman 207-9).

Copyright

Copyright 2009, Department of Special Collections, Memorial Library, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI

Publisher

R. Blamire

Collection

Additional Information

Bibliography

Andrews, Malcolm. The Search for the Picturesque: Landscape Aesthetics and Tourism in Britain, 1760-1800. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1989. Print.

Barbier, Carl Paul. William Gilpin: His Drawings, Teaching, and Theory of the Picturesque. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1963. Print.

Bermingham, Ann. "The Picturesque and Ready-to-wear Femininity." The Politics of the Picturesque: Literature, Landscape, and Aesthetics since 1770. Ed. Stephen Copley and Peter Garside. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1994. Print. 81-119.

Byng, John. Byng's tours: The Journals of the Hon. John Byng, 1781-1792. Ed. David Souden. London: Century in Association with The National Trust, 1991. Print. National Trust Classics.

Gilpin, William. Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales, &c.: Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; Made in the Summer of the Year 1770. 5th ed. London, 1792. Print.

Janowitz, Anne F. England's Ruins: Poetic Purpose and the National Landscape. Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1990. Print.

Lowenthal, David. The Past is a Foreign Country. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1985. Print.

Mavor, William Fordyce. The British Tourists; or Traveller's Pocket Companion, through England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. Comprehending the Most Celebrated Tours in the British Islands. Vol. 4. London, 1798-1800. Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Gale. University of Wisconsin - Madison. Web. 15 May 2009.

Templeman, William D. The Life and Work of William Gilpin (1724-1804): Master of the Picturesque and Vicar of Boldre. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1939. Print. University of Illinois Studies in Language and Literature 24.3-4.