Creation Date

1789

Height

35 cm

Width

25 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

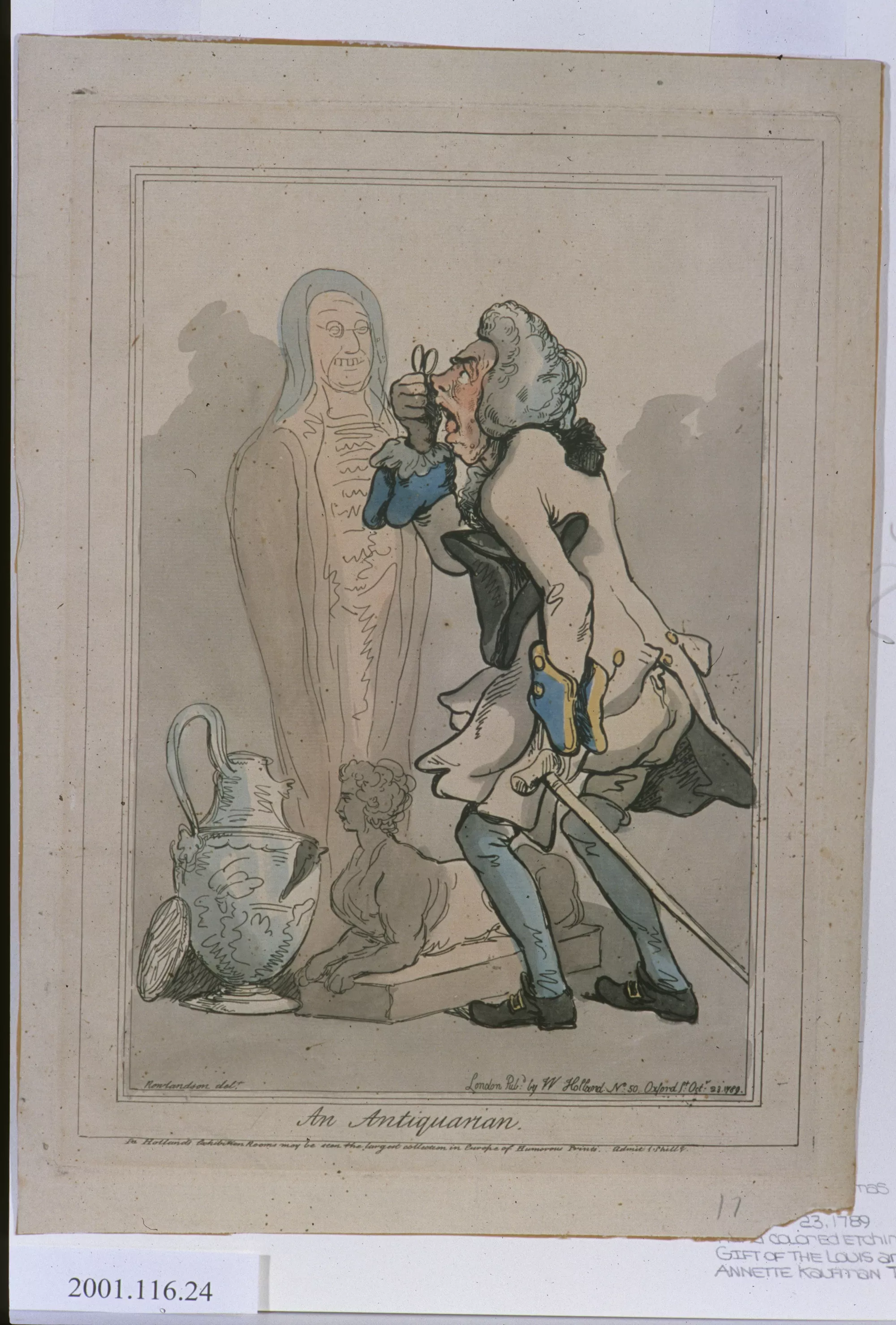

The print depicts an antiquarian engaged in the study of several ancient artifacts. The object that most engrosses him, the mummy, seems to both mirror his image and return his gaze. Consequently, the print conflates the student of antiques with the art objects he studies, troubling notions of subjectivity, objecthood, and alterity.

An antiquarian holds up his spectacles in his right hand to examine an object that resembles an Egyptian mummy. He stoops and holds a cane in his left hand, a tri-corner hat under his arm. He is dressed in breeches and a coat with deep cuffs and prominent buttons, a wig, and buckled shoes. He wears blue worsted stockings, an informal alternative to silk ones, and the typical designation of a “bluestocking” or intellectual. A frilly cravat and shirt cuffs are visible beneath his coat. An Egyptian sphinx and a large vase that resembles an oenochoe, an ancient Greek wine jug, lie at the antiquarian's feet.

In this print, the student of art objects is conflated with the art objects he studies. This conflation is primarily effected by the antiquarian's elderly age, which seems to categorize him with the ancient objects he examines. The comparison is made more direct by the Egyptian mummy, whose grey hair and spectacles mirror those of the antiquarian: the living person and the objectified human remains become interchangeable. Similarly, the lips of the oenochoe are puckered up as if it were going to kiss the sphinx, an entity that is even more explicitly a combination of the human and the non-human. The reduction of the human figure to the status of an antique object and the corresponding anthropomorphism of those antiquities recalls the eighteenth-century fascination with it-narratives and thing poems; furthermore, this conflation suggests the similar roles of the antiquarian type and the antiquities he studies as commodities for circulation. The antiquarian not only becomes a commodity by selling his services in the cultural marketplace, but also by becoming the subject of satirical prints that were exchanged commercially.

The juxtaposition of ancient Greek and ancient Egyptian artifacts is curious given the very different attitudes towards these cultures in eighteenth-century Britain. While ancient Greece was considered the cradle of Western civilization, ancient Egypt was negatively perceived as an exotic and degenerate culture (Barrell). However, both Greece and Egypt were part of the Ottoman Empire during the nineteenth century, and so the juxtaposition of their artifacts in the print enables the antiquarian to first, gloss these distinct ancient cultures and second, to conflate the modern empire with the ancient, static, and objectified Orient. The occidental antiquarian is therefore granted the right to inspect, examine, and study the oriental "Other." And yet, the print’s conflation of these ancient artifacts with the human antiquarian suggests that the Other can look back in a way that is both humorous and unsettling to the Occident’s assumption of power.

Locations Description

The antiquities depicted in this image reference ancient Egypt and ancient Greece, both of which were controlled by the Ottoman Empire at the time this print was produced.

Publisher

W. Holland

Collection

Accession Number

2001.116.24

Additional Information

Bibliography

Allan, D.G.C. and John Lawrence Abbott, eds. The Virtuoso Tribe of Arts and Sciences: Studies in the Eighteenth-Century Work and Membership of the London Society of Arts. Athens, GA: U of Georgia P, 1992. Print.

"antiquarian, adj. and n." The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. OED Online. June 2013. Oxford UP. 19 August 2013.

Barrell, John. The Birth of Pandora and the Division of Knowledge. Philadelphia: U Pennsylvania P, 1992. Print. New Cultural Studies Series.

Bending, Stephen. “Every Man is Naturally an Antiquarian: Francis Grose and Polite Antiquities.” Art History 25.4 (2002): 520-30. Print.

Bignamini, Ilaria. “George Vertue, Art Historian, and Art Institutions in London, 1689-1768: A Study of Clubs and Academies.” Walpole Society Annual 54 (1988): 1-148. Print.

Brown, Bill. “Thing Theory.” Critical Inquiry 28.1 (2001): 1-21. Print.

Clark, Peter. British Clubs and Societies, 1580-1800: The Origins of an Associational World. New York: Oxford UP, 2000. Print.

Copley, Stephen. “Gilpin on the Wye: Tourists, Tintern Abbey, and the Picturesque.” Prospects for the Nation: Recent Essays in British landscape, 1750-1880. Ed. Michael Rosenthal, Christiana Payne, and Scott Wilcox. New Haven: Yale UP, 1997. Print. The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

Evans, Joan. A History of the Society of Antiquaries. Oxford UP, 1956. Print.

Mack, Ruth. “Horace Walpole and the Objects of Literary History.” ELH 75 (2008): 367-387. Print.

Momigliano, Arnaldo. “Ancient History and the Antiquarian.” Studies in Historiography. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1966. Print.

Myrone, Martin and Lucy Peltz, eds. Producing the Past: Aspects of Antiquarian Culture and Practice, 1700-1850. Brookfield, VT: Ashgate, 1999. Print.

Piggott, Stuart. Ancient Britons and the Antiquarian Imagination: Ideas from the Renaissance to the Regency. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1989. Print.

---. Ruins in a Landscape: Essays in Antiquarianism. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 1976. Print.

Scott, Johnson. The Pleasures of Antiquity: British Collectors of Greece and Rome. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Print.

Soros, Susan Weber, ed. James “Athenian” Stuart, 1713-1788: The Rediscover of Antiquity. Exhibition Catalogue. New Haven: Yale UP, 2006. Print.

Sweet, Rosemary. “Antiquaries and Antiquities in Eighteenth-Century England.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 34.2 (2001): 181. Print.

---. Antiquaries: The Discovery of the Past in eighteenth-century Britain. London: Hambledon and London, 2004. Print.