Creation Date

c. 1760; 1835–9

Height

54.5 cm

Width

40.7 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

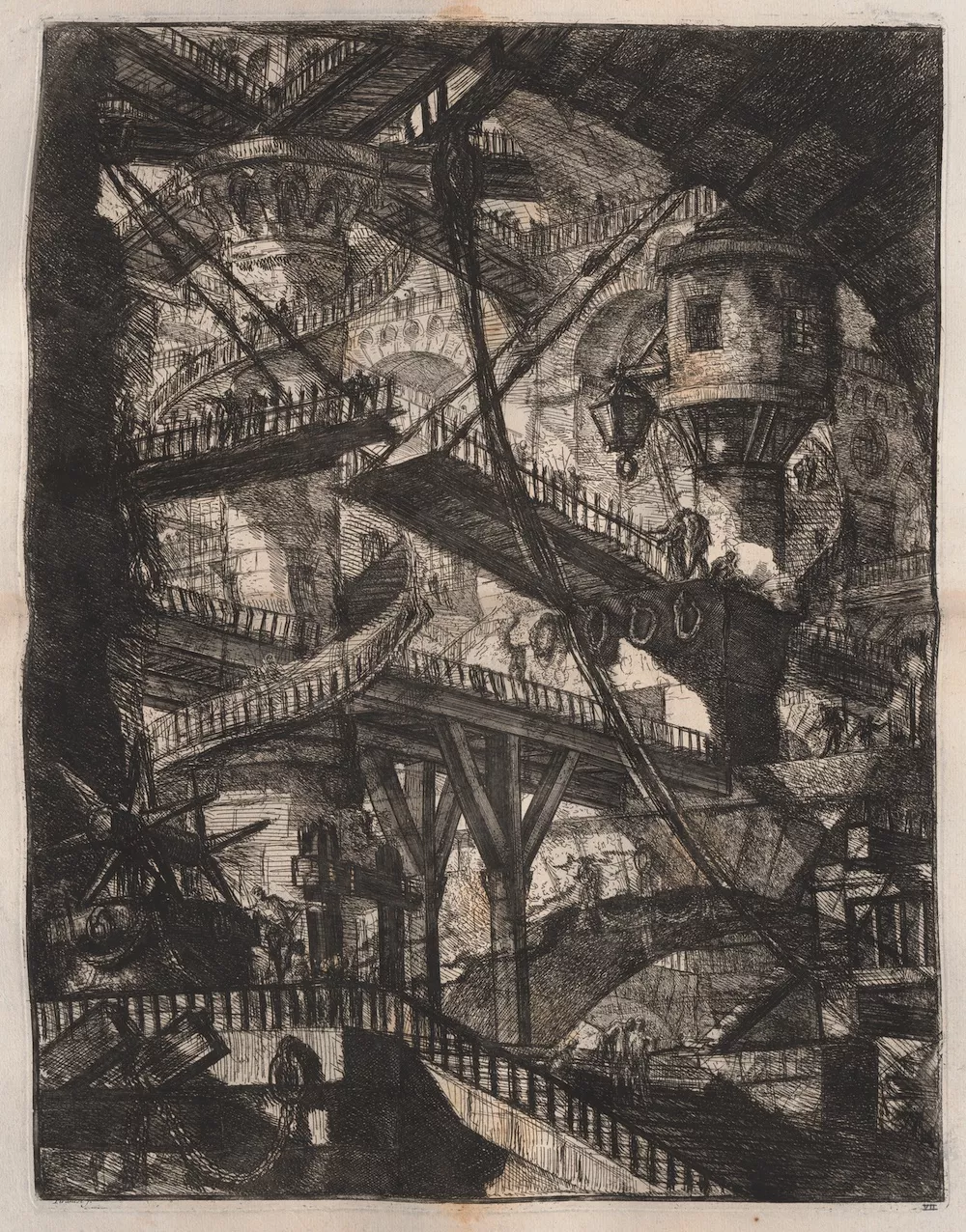

Piranesi’s Carcerid’Invenzione is a series of 16 menacing, mysterious etchings that depict impossible architectural structures inhabited by laboring, manacled, or tortured men. The series originally appeared in the 1740s as Invenzioni capric. di Carceri., including an abbreviation of “capriccio” [“caprice” or “fancy”]. Piranesi returned to it about 15 years later, adding two images, deeper shadows, new details, and a new title: Carceri d’Invenzione. The revised title and its genitive grammar raise a few questions. Are these prisons of the imagination because the imagination itself a prison, or because it has created prisons? Are these images, as the original title page suggests, examples of the capriccio genre? Does the second state reject this generic designation? Do these spaces suggest the power of some absent authority or the dark depths of the human mind? These ambiguities persist and expand within each of image of the series.

In the medium of copper-plate engraving, the genre of the caprice is something of a contradiction. Historically, engraving was not considered a medium for artistic creativity. Widely used to render faithful depictions of architectural or landscape views, portraits, and scientific specimens, it did not enjoy the status of “fine arts” such as painting or sculpture. Over the course of his career, Piranesi validates the status of engraving as a medium for creativity and not just reproduction. This is perhaps more true of this series than any of his other works.

Broadly speaking, the series has been understood to suggest the threat of unjust power and the irrationality of the imagination. Piranesi did not give the images individual titles; scholars later bestowed the title “The Drawbridge.” Its portrait orientation provides ample space for a repetitive pattern of ascending staircases and walkways. A drawbridge to the left of the image’s center ruptures its seemingly endless climbing stairs with the implicit danger of plunging into unknown depths. If the subject matter is repetitive and threatening, the etching technique is, especially compared to the precision of the other images in this gallery, erratic or even frenzied.

As a group, these images were profoundly inspirational for many Romantic-era authors. The most famous and direct response is Thomas De Quincey’s meditation on Piranesi in his Confessions of an English Opium Eater (1821), which, as the full citation shows, resembles the repeating staircases of “The Drawbridge”:

Many years ago, when I was looking over Piranesi’s Antiquities of Rome, Mr. Coleridge, who was standing by, described to me a set of plates by that artist called his Dreams, and which record the scenery of his own visions during the delirium of a fever. Some of them (I describe only from memory of Mr. Coleridge’s account) represented vast Gothic halls, on the floor of which stood all sorts of engines and machinery, wheels, cables, pulleys, levers, catapults, &c. &c., expressive of enormous power put forth and resistance overcome. Creeping along the sides of the walls you perceived a staircase; and upon it, groping his way upwards, was Piranesi himself: follow the stairs a little further and you perceive it come to a sudden and abrupt termination without any balustrade, and allowing no step onwards to him who had reached the extremity except into the depths below. Whatever is to become of poor Piranesi, you suppose at least that his labours must in some way terminate here. But raise your eyes, and behold a second flight of stairs still higher, on which again Piranesi is perceived, but this time standing on the very brink of the abyss. Again elevate your eye, and a still more aerial flight of stairs is beheld, and again is poor Piranesi busy on his aspiring labours; and so on, until the unfinished stairs and Piranesi both are lost in the upper gloom of thehall. With the same power of endless growth and self-reproduction did my architecture proceed in dreams. In the early stage of my malady the splendours of my dreams were indeed chiefly architectural; and I beheld such pomp of cities and palaces as was never yet beheld by the waking eye unless in the clouds. (69-70)

De Quincey’s description of seeing a set of Piranesi’s engravings records the scenery of his own deeply immersive, dreamlike, hallucinatory visions. He imagines entering architectural spaces that stretch the limits of physical possibility, and, once there, he follows endless staircases on fruitless paths of pursuit. In his influential reading of De Quincey, J. Hillis Miller identified as “the Piranesi effect” “the power which the mind has to sink into its own infinite abyss, not by emptying itself out, but by becoming trapped in some form of thought or mental experience which is repeated forever.” In De Quincey’s account, Piranesi himself is located, erroneously, in the prisons, endlessly climbing staircases. As Miller puts it, “the upper end of each staircase hangs in the void, and if Piranesi should ever reach the top an infinity of climbing will be followed by an infinity of falling.” (Miller 67, 69)

Endless movements interconnect Piranesi’s other, equally astounding, works in ways that are informative rather than imaginative. Peppered with archaeological, architectural, and historical annotations, they follow a logic of cross-reference and annotation that creates a very literal instance of “the Piranesi effect” that Miller identified. With its infinite movement into ever-reproducing spaces, this so-called effect parallels the continuous movement of the cross-references that, as other works in this gallery show, animate Piranesi’s own kaleidoscopic word-image composites.

Printing Context

The versions of the etchings included in this exhibit come from the Didot edition of Piranesi’s Opere [Works] published in Paris between 1835 and 1839. They thus of course represent the final state and include any reworking for printings that followed the plates’ original pressings. The journey of Giambattista Piranesi’s original copper plates from Rome to Paris is directly tied to international military and state affairs. In 1798 during the upheaval following the French Revolution, Neapolitan troops invaded Rome. The Piranesi print shop and museum was ransacked, and all of the copper plates stolen. Francesco appealed to French officials to have the plates returned; after an interception by an English warship, the plates were reunited with Francesco and his brother Pietro, who had both fled to Paris. After Francesco’s death in 1810 and many potential and actual sales, the plates were eventually acquired by the Didot press. A dynastic printing house for two centuries, the Didot family were major innovators in printing and recipients of international awards for typography.

Associated Persons

Publisher

Firmin Didot

Collection

Accession Number

NE 662.P5 A2 vol. 8

Additional Information

This digital image is from a complete 29-volume set of Piranesi’s posthumous Opere (1835-1839) held by the Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, University Libraries, at the University of South Carolina. It was scanned in the Digital Collections Department. The set was likely acquired directly from the publisher, and the cover of each volume bears the imprint of the name of the university up through 1866: South Carolina College.