Creation Date

19 September 1846

Height

48 cm

Width

37 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

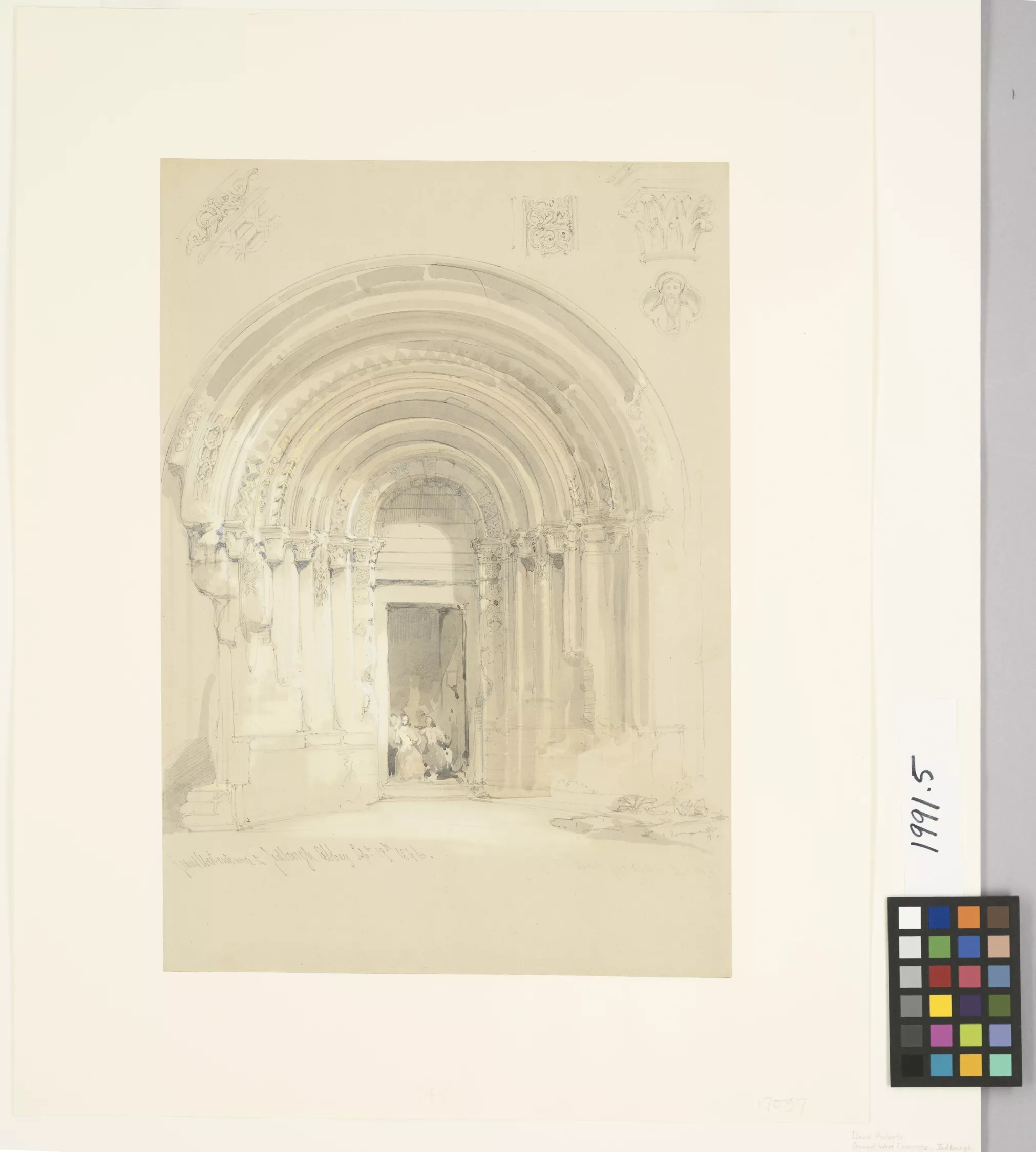

The choice of subject in this piece, a crumbling medieval monastery situated on the border between Scotland and England, can be interpreted as a temporally and spatially liminal place; the presence of the ruins collapses not only the present and the past, but also the national identities of the English and the Scottish. Jedburgh Abbey is a British space that is simultaneously familiar and unfamiliar, foreign and domestic. An abbey that over the course of its existence housed both Scottish nationalists and English monarchists, as well as divinely inspired abbots like Kennoch, Jedburgh is a triple symbol of political strife, nationalistic desires, and religious devotion (Morton 6). As a painter of ruins and ecclesiastical buildings in Scotland and England, as well as on the Continent and in the Holy Land, Roberts becomes the quintessential painter of ruins, turning his attention to both the domestic and the foreign. This particular watercolor is intriguing: the grand entrance to the abbey is de-contextualized or divorced from the rest of the edifice and seems to appear suddenly out of the pristine white background of the canvas. The fragmentation of an already fragmented ruin is further emphasized by the seemingly random insertion of statuary remains in the right and left upper register of the painting. By zeroing in on the arched doorway and isolating it from the rest of the abbey, Roberts de-familiarizes the abbey to the extent that it can represent any medieval edifice.

The Grand West Entrance to Jedburgh Abbey is at the perfect center of the composition. The sequence of intricately carved arches framing the comparatively small, rectangular door creates a tunneling effect, drawing the eye of the viewer to the center of the door. The brown block of color marking the doorway to the former Augustinian monastery stands out against the beige wash of the watercolor sketch, but the dilapidated, Romanesque doorjambs and the arches rising from them are the focus of the piece. Roberts manages to convey the general form of the abbey portal even in his delicate outlines of the foliate capitals and the incomplete crossing and chevron patterns on the arches and column shafts, other faint images of which are placed above the archway. A bust in a quatrefoil accompanies these detached drawings above the arched entrance. Three shadowy figures, women clothed in expansive skirts, block the entrance to the abbey.

After his early apprenticeship years in the decorative arts in Edinburgh, the Scottish-born Roberts gained employment as a scene-painter at Drury Lane in London, 1832. Dissatisfied with his commissions, he began to focus on easel painting and joined the artist-run Society of British Artists in 1823. His sketches of Rouen Cathedral, made after traveling to France in 1823, were exhibited by the Society of British Artists in 1825 and garnered favorable attention. He traveled next to Belgium, and he returned to France several times on sketching trips. Sketches of ruins and churches based on these travels to the Continent and his homeland were also well received at exhibitions of the Society of British Artists, the British Institution, and the Royal Academy. Most of his etchings feature ecclesiastical ruins, chapels, cathedrals, temples (and other “exotic” structures), as well as the classical ruins of Rome, Greece, and the Holy Land; his experiences with architecture led him to become involved with the architectural preservation campaign in Scotland in the 1830s. He continued to travel in Scotland, France, Italy and Spain throughout the 1840s and 50s, and this particular work (Jedburgh Abbey) was completed just after a trip to Bruxelles and Antwerp in 1845 (Matyjaszkiewicz). In 1846, Roberts was commissioned to complete a series of drawings for a compilation that would be published as Scotland Illustrated. In the fall of that year he toured and made sketches of prominent Scottish ruins and locations (Ballantine 163). In spite of his accurate depiction and recreation of the historic venues in his watercolors, reviews of the work were disappointing. As Robert Cadell, a well-known publisher at the time, noted in a letter to the artist, the collection was “most credible,” but “it has two drawbacks: the first, it is rather late; the second, too dear” (qtd. in Ballantine 231). Cadell went on to explain that to be attractive to the public—a fickle entity that he referred to as “the many-headed beast”—artistic representations of such landmarks must have a “dash of originality” or “novelty” (qtd. in Ballantine 231).

On October 14th, 1285, King Alexander III married Jolande, daughter of the Count of Dreux, in the town of Jedburgh, a location that was chosen for its natural beauty. Unfortunately, the regal celebration was sobered by the unexplained appearance of a premonitory apparition, “whose mysterious and singular appearance startled the beholders, who were in doubt whether they saw a human being or a phantom; for, like a shadow, it seemed to glide, rather than walk” (Morton 7-8). The foreboding nature of this appearance was later confirmed by the untimely death of King Alexander when he was thrown from his horse on March 19, 1286, an event that led to civic and political unrest and resulted in the intervention of King Edward I of England (Morton 7-8).

Following her trip to Scotland in 1803, Dorothy Wordsworth—English author, poet, diarist, and sister to William Wordsworth—stayed near Jedburgh Abbey in accommodations provided her by the Scottish poet and novelist Walter Scott. In her diary, she noted the following:

The churchyard [of Jedburgh Abbey] was full of graves, and exceedingly slovenly and dirty; one most indecent practice I observed: several women brought their linen to the flat table-tombstones, and, having spread it upon them, began to batter as hard as they could with a wooden roller, a substitute for a mangle. (Wordsworth 212)

Wordsworth’s comments raise a significant question about Roberts’s sketch of this ruined, Augustinian friary: who are the central figures in the doorway, and what are they doing there? Are they the ancestors of the women described by Wordsworth or, like Wordsworth herself, are they visitors to Jedburgh? Although the figures are not clear in the drawing, their flared dresses suggest that they are tourists.

Dorothy Wordsworth’s comments on the state of abbeys reflect a more general sentiment among tourists that all heritage sites, including medieval ruins, should be well maintained. In his tour of Britain in the 1790s, John Byng made similar remarks bemoaning the unkempt state of several English ruins (Byng 144; 179-80; 208). After the Continent closed to tourists in the aftermath of the French conflicts of the late eighteenth century, domestic travel flourished in Great Britain, and the manmade structures of centuries past that dotted the British countryside became popular destinations. Scholars such as Malcolm Andrews and Ann Janowitz claim that these sites became central points in the discourse surrounding the creation of a single British nation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: the medieval buildings and their decaying remnants embodied the longevity of the British Isles and served to unite three cultural groups of Great Britain, the English, the Welsh, and the Scottish. Travel logs from the Romantic period support these conclusions. In Thomas Newte’s 1785 journey to Scotland, he writes of Inverary:

[T]he whole appearance of the castle, town, and environs . . . is such as beseems the head of a great clan, in a strong and mountainous country, who, without losing sight of the origin of his family, in rude and war like times, adopts the improvements of the present period. (qtd. in Mavor 255)

Newte also refers to the growing Scottish fishing industry as an asset to the British (Mavor 254). National differences among the Scottish, Welsh, and English are not effaced in this Englishman’s log, but Newte implies that the Scottish, in their labor and in the beauty of their architectural heritage, contribute to the edification of Britain as both a moral and a unified nation.

There is, however, nothing “Scottish” about Roberts’s west portal to Jedburgh Abbey. It is detached from the town of Jedburgh and from the rest of the abbey itself. The sketches above the archway highlight the decorative details of the arches and capitals in the central part of the piece, but these patterns are not different from the chevron masonry found in Norman structures, such as those at Pevensey in East Sussex, or the intricate interlacing motifs of Hiberno-Saxon manuscripts from the early medieval period. McAleer and Stalley’s architectural studies of medieval abbeys in Britain confirm that Jedburgh and other Romanesque structures in England shared architectural forms and decorative motifs. Consequently, the medieval subject of Roberts’s piece, his sketchy rendering of the portal, and the ambivalent figures in the doorway could be interpreted collectively to convey the idea of a unified Britain by means of both generalization and de-familiarization.

Locations Description

The town of Jedburgh was founded by the Bishop of Lindisfarne and is the location of the Ferniherst Castle and Jedburgh Abbey ruins. The town sits on the Jed River and is surrounded by beautiful wooded areas. Built in 1490 by Sir Thomas Ker, Ferniherst Castle was damaged during the Border Wars between 1544 and 1550 and partially rebuilt in 1598 (Morton 11). The Jedburgh Abbey was initially founded by King David I in 1138, and was later inhabited by Augustinian Friars. In his study of Romanesque abbeys in Britain, J. Philip McAleer states that the Roxburghshire abbey of Jedburgh began as a priory. According to the Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions (Scotland), cited by McAleer, interior parts of its structure were built in several phases, the earliest of which was begun in c. 1152. This shortly predates the elevation of the priory in 1154 to an Augustinian abbey (McAleer 536 n.3). Following Edward of England’s succession to the throne in 1296, the monastery was also used for meetings held by Scottish nationalists. When war was rekindled in 1297, the abbey was “not only plundered, and the conventional buildings unsparingly destroyed, but the lead was stripped off the roof of the church, and was detained by Sir Richard Hastings” (Morton 11). Although it was subsequently rebuilt in the 1300s, later attacks and substantial damage followed throughout the 1400s and in 1523, when the Earl of Surrey and an English army badly damaged the abbey. Subsequent reconstruction was on a more limited scale, and many parts of the abbey remain in a state of disrepair (Morton 11). McAleer does not mention if the portal, as seen in Roberts’s watercolor, is from the initial construction period or the later one.

Collection

Accession Number

1991.5

Additional Information

Bibliography

Andrews, Malcolm. The Search for the Picturesque: Landscape Aesthetics and Tourism in Britain, 1760-1800. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1989. Print.

Ballantine, James. The Life of David Roberts, R.A.: Compiled From His Journals and Other Sources. Edinburgh, 1866. Print.

Elliot, C. A Catalogue of the Valuable and Choice Collection of Books, Prints, Books of Prints, Sketches, Original Drawings, Portraits, Paintings, the Property of the Late David Martin, Esquire, Portrait Painter to His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales. Which will be Sold by Auction, viz. the Books, and Part of the Prints, by C. Elliot, and the Other Articles - by William Bruce, on Monday the 14th of January 1799, at Mr. Martin's House, no. 4. St. James's Square, Edinburgh. Edinburgh, 1799. Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Web. 16 Aug. 2013.

Gough, Richard. British topography. Or, an Historical Account of What has Been Done for Illustrating the Topographical Antiquities of Great Britain and Ireland. Vol. 2. London, 1780. Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Web. 16 Aug. 2013.

Grose, Francis. The Antiquities of Scotland by Francis Grose. Vol. 1. London, 1789-91. Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Web. 16 Aug. 2013.

Janowitz, Anne F. England's Ruins: Poetic Purpose and the National Landscape. Cambridge: Blackwell, 1990. Print.

Matyjaszkiewicz, Krystyna. “Roberts, David (1796–1864).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Web. 13 May 2009.

Mavor, William Fordyce. The British Tourists; or, Traveller's Pocket Companion, through England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. Comprehending the Most Celebrated Tours in the British Islands with Several Originals in Six Volumes. 3d ed. London, 1814. Print.

McAleer, J. P. “The Romanesque Choir of Tewkesbury Abbey and the Problem of a ‘Colossal Order.’” The Art Bulletin 65.4 (1983): 535-58. Print.

Morton, James. The Monastic Annals of Teviotdale: or, the History and Antiquities of The Abbeys of Jedburgh, Kelso, Melros, and Dryburgh. Edinburgh, 1830. Print.

Stalley, Roger, “Choice and Consistency: The Early Gothic Architecture of Selby Abbey.” Architectural History 38 (1995): 1-24. Print.

The Itinerant; a Select Collection of Interesting and Picturesque Views, in Great Britain and Ireland: Engraved from Original Paintings & Drawings, by Eminent Artists. London, 1799. Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Web. 16 Aug. 2013.

Wordsworth, Dorothy. Recollections of a Tour Made in Scotland. New Haven: Yale UP, 1997. Print.