Creation Date

c.1842; engraving and publishing date between 1842-1844

Height

18 cm

Width

16 cm

Medium

Description

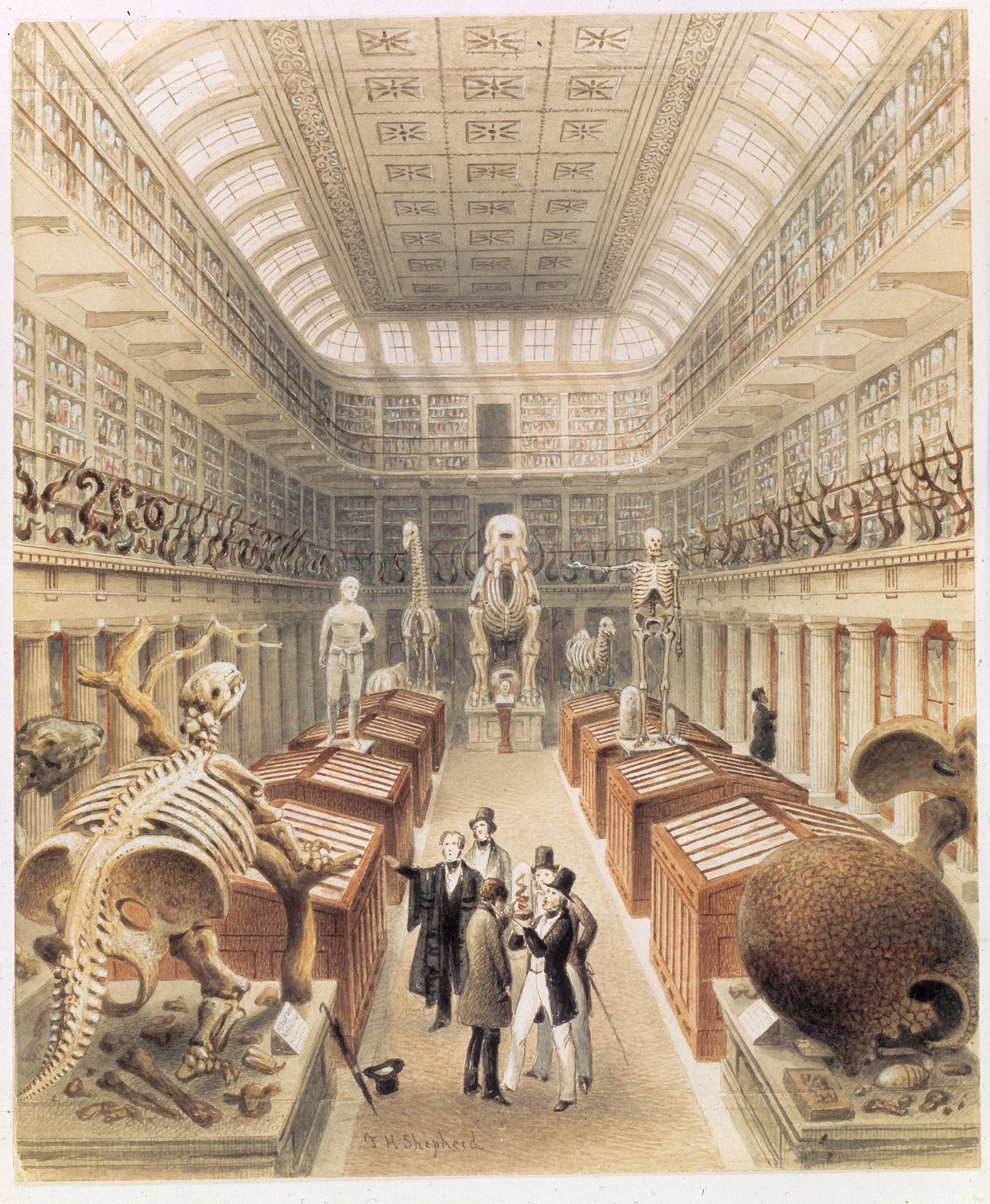

This image documents the “Crystal Room” of the Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) as it was arranged in 1842. The two foremost specimens are a skeleton of the Mylodon (a large land-sloth from the ice age) on the left, and an armored shell of the Glyptodon (a large relative of the armadillo, also from the ice age) on the right. Towards the back, on the right, stands the skeleton of Charles Byrne, the “Irish Giant” (whose remains John Hunter acquired illegally and against Byrne’s wishes), and the skeleton of Caroline Crachini, the “Cicilian Dwarf.” Along the rear wall, on the left, stands the skeleton of a giraffe (the first ever to be displayed in Britain); in the center is the skeleton of Chunee, the “mad” elephant of Exeter Change; and on the right, the skeleton of what is possibly a kangaroo, brought to England by Capt. James Cook following his seminal voyages to Oceania. In front of the elephant, although difficult to discern, rests a bust of Hunter himself. Atop the colonnade circling the Crystal Room are numerous horns and antlers from large mammals, and along the second tier are shelves housing countless preparations such as whole animals, organs (belonging to both humans and animals), and plants.

Shepherd’s watercolor, produced in 1842, was primarily made to document new and notable specimens contained within the College’s museum spaces. In addition, it shows off the new Crystal Room, which was completed only five years earlier. Shepherd’s painting was reproduced in London Interiors, a two-volume collection published between 1841 and 1844 that functioned as, in the words of its subtitle, “a grand national exhibition of the religious, regal, and civic solemnities, public amusements, scientific meetings, and commercial scenes of the British capital,” complete with illustrations that were “beautifully engraved on steel, from drawings made expressly for this work, by command of Her Majesty.”

John Hunter (1728 - 1793), a Scottish surgeon based in London—and brother of the surgeon William Hunter, whose collection forms the basis of the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow—amassed nearly 14,000 specimens, for the study of anatomy and pathology, over the course of his life. The collection was first displayed at his house in Leicester Square, in a specially designed annex situated above his lecture and meeting rooms (Thomas 686). It was here that Hunter used his specimens, many of which he prepared himself, as a teaching tool for pupils and colleagues. While his scientific collecting was driven primarily by professional and pedagogical considerations, he has also been described as a “magpie who indiscriminately swept together ‘waxworks, portraits of freaks, Oriental scrimshaw, exotic weapons, scraps of tapestry, [and] electromagnetical novelties’” (Altick 28). This collecting mania led him into debt, and after his death in 1793 there was neither a suitable permanent home nor an immediate buyer for the collection.

It was not until six years later that Hunter’s entire collection was purchased by the British Government for 15,000 pounds, and, after being refused by the British Museum and the Natural History Museum, was accepted by the Royal College of Surgeons (then the Company of Surgeons). The first exhibition space, designed by George Dance and Nathaniel Lewis, was opened to the public on the 18th of May 1813. However, it was soon deemed insufficient to house the growing collection, and the RCS was renovated and expanded in 1834 according to the designs of Charles Barry. The resulting museum, which opened four years later, is the iteration depicted in Shepherd’s image. Barry’s Crystal Room, also referred to as the “East Museum” or “Room III,” augmented Dance and Lewis’s original design by adding a “second gallery, putting in a flat roof lighted obliquely from the ceiling and substituting small cast iron columns for the present large wooden projections” (Dobson 119).

In addition to dividing his specimens on the basis of ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy,’ Hunter organized his collection into two main categories or classes: “The first showed the relationship between bodily structures and functions. […] The second class demonstrated ‘generation’: the reproduction and development of plants and animals” (Alberti 14). All items occupied a singular place in an overarching series that revealed the underlying principles of anatomy and pathology, for his overall design was “to furnish an ample illustration of the phenomena of life exhibited throughout the vast chain of organized beings” (Walton 2). Hunter’s attention to hereditary genealogy is particularly groundbreaking when we consider that he began collecting in the late eighteenth century, more than seventy years before Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species (1859). When the RCS took possession of Hunter’s collection after his death, the conservators embraced this educational function and continued to arrange the collection according to demonstrable scientific principles.

Both Hunter and the RCS’s curators thus distinguish themselves from natural history collectors such as Ashton Lever or William Bullock, whose museums were based on far looser organizational schemes. As this image shows, a visibly didactic order is maintained in the Crystal Room’s arrangement: the space is well-lit, clean, and for the time being, contemporary. The contents of the collection are arranged in neat lines, and like the British Museum’s “Egyptian Room,” the practice of arranging specimens in balanced opposition to one another lends an air of symmetry to the gallery. In an 1850 review of the Royal College’s Hunterian collection, published in the journal Household Words, Frederick Hunt observes that:

with this multiplicity of things we see no confusion, or trace of carelessness or poverty. All is neatness, order, and repose. Not a particle of dirt offends the eye; not a film of dust dims the brilliancy of the regiments of bottles drawn up in long files upon the shelves, to salute the visitor. This place is a very drawing-room of science, all polished and set forth in trim order for the reception of the public. It is the best room in the house kept for the display of the results of the labours of the physiologist, a spot devoted to the revelations of anatomy, without the horrifying accompaniments of the dissecting-room (464).

Shepherd’s watercolor reflects this description effectively. He presents the specimens as objects that, while previously associated with Gothic scenes of macabre fascination, had been “reclaimed” by scientific discourse under the College’s curation. To emphasize this, Shepherd places the tour-leader (the RCS’s then-Conservator Richard Owen) in the center of the image and depicts him gesturing authoritatively to visitors who are clearly present with the aim of being educated, as opposed to being shocked or entertained.

However, in spite of the gallery’s cleanliness, arrangement, and devotion to science, its anatomical displays still carried with them many of the Gothic or Medieval associations long held with bodily dissection and preservation. Verity Burke writes that “the atmosphere of the dissection room is hybrid, composed partly of objects traditionally associated with the supernatural … and partly the instruments of scientific discovery,” and notes that this thematic hybridity rendered anatomical displays as “institutions that could house medical ‘monsters,’ yet still embody the educational ideals of the modern museum” (15–7). The theme of Gothic-meets-science, therefore, reflects the Enlightenment’s preoccupation with negotiating the meeting point between the unknown world of the Dark Ages and the discovery, progress, and knowledge of the emerging Modern world.

Although many of the 14,000 specimens that originally belonged to Hunter’s house-museum collection were transported to the Royal College after his death, no more than a third of his personally prepared specimens remain today. In 1941 the College took a direct hit from a German bombing run, and the majority of the original collection was lost. The Crystal Room survived the Blitz, but was demolished in 1960. Despite wartime losses and continual reinvention and expansion, the original collection is still very much the celebrated core of today’s Hunterian museum.

Associated Persons

Copyright

©Museums at the Royal College of Surgeons of England

Publisher

Published by J Mean in London Interiors between 1842 and 1844. Reproduced in Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons 1950, 6, p.346.

Collection

Accession Number

RCSSC/P 318

Bibliography

Adams, Ellen. “Shaping, Collecting and Displaying Medicine and Architecture: A Comparison of the Hunterian and Soane Museums.” Journal of the History of Collections, vol. 25, no. 1, 2013, pp. 59–75.

Adams, Joseph. Memoirs of the Life and Doctrines of the Late John Hunter, Esq., Etc. Printed by W. Thorne and published by J. Callow; J. Hunter; and J. Ridgway, 1817.

Alberti, Sam (et al.) “Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons: Guidebook.” Printed by the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

Anon. “The Hunterian Museum.” Household Words/Conducted by Charles Dickens, vol. 2, no. 38, 1850, pp. 277–82.

Anon. “The Hunterian Museum.” Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons England, vol. 61, no. 2, 1958, pp. 202–7.

Burke, Verity. “‘A Regiment of Skeletons and an Army of Bottles’: Reading the Hunterian Museum in Nineteenth-Century Scientific and Popular Culture.” Romanticism on the Net, no. 70, 2018, pp. 2–17.

Dobson, Jessie. “The Architectural History of the Hunterian Museum.” Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, vol. 29, no. 2, 1961, pp. 113–26.

———. “The Place of John Hunter’s Museum.” Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, vol. 33, no. 1, 1963, pp. 32–40.

Hunt, Frederick. “What there is in the Roof of the College of Surgeons.” Household Words, vol. 1, 1850, p. 464.

Rajan, Tilottama. “Elements of Life: Editing and Arranging the Work of John Hunter.” Studies in Romanticism, vol. 59, no. 1, 2020, pp. 133–59.

Shepherd, Thomas H. London interiors: a grand national exhibition of the religious, regal, and civic solemnities, public amusements, scientific meetings, and commercial scenes of the British capital: beautifully engraved on steel, from drawings made expressly for this work, by command of Her Majesty, and with permission of the proprietors and trustees of the metropolitan edifices: with descriptions written by official authorities. Joseph Mead, 1841–1844.

Thomas, Sophie. “Collection, Exhibition, and Evolution: The Romantic Museum.” Literature Compass, vol. 13, no. 10, 2016, pp. 681–90.

Walton, James. “The Hunterian Ideals To-Day.” British Journal of Surgery, vol. 35, no. 137, 1947, pp. 1–6.

The Hunterian Museum © 2024 by Sophie Thomas, Rhys Jeurgensen, Erin McCurdy, and Romantic Circles is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0