Creation Date

1764

Height

17 cm

Width

18 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

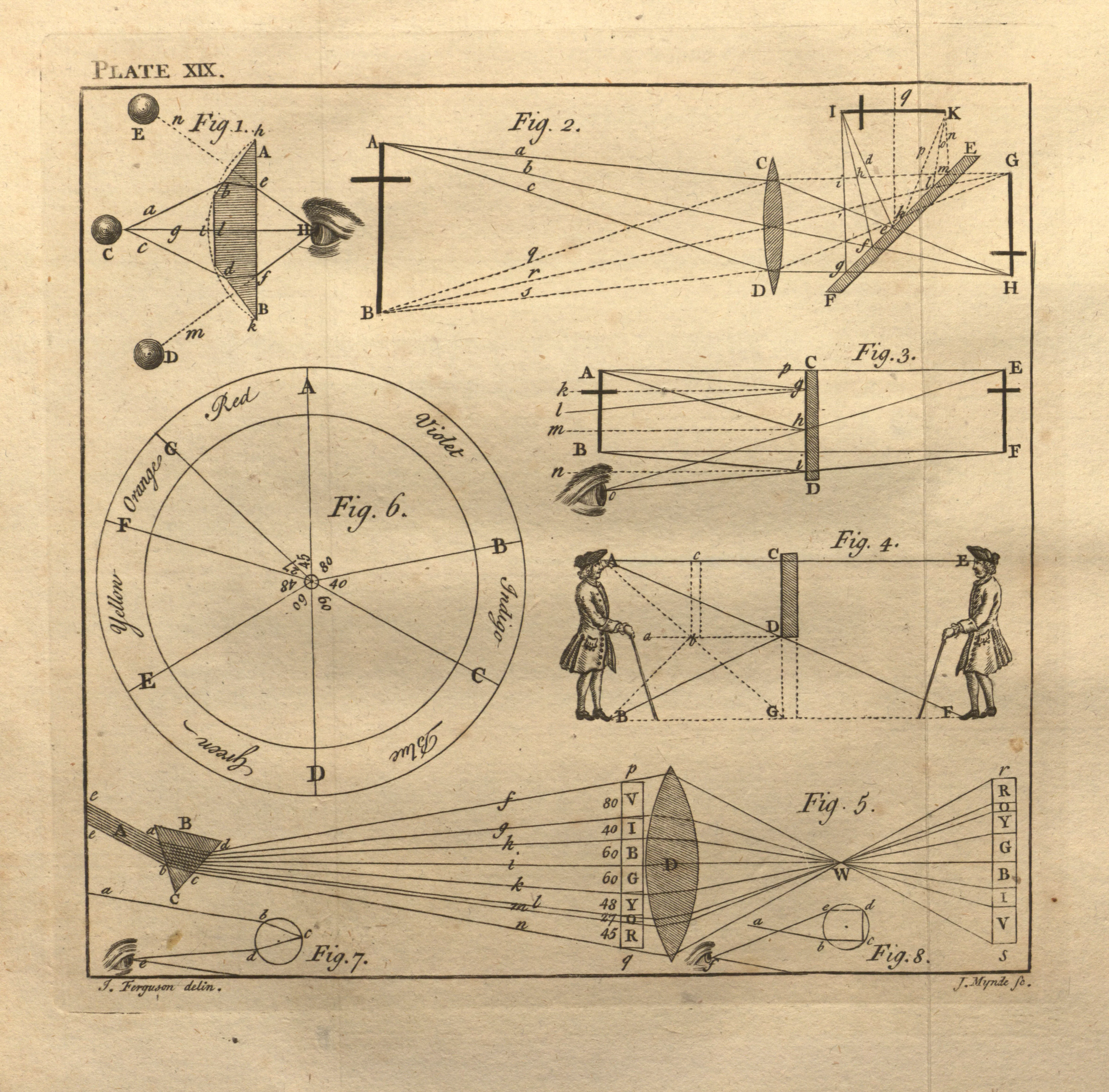

The camera obscura portrayed here is an excellent example of Ferguson’s interest in the physical properties of the scientific problem at hand. Instead of illustrating a portable box camera obscura with a cut-away side view to reveal the inner mechanisms of lens and mirror, Ferguson, the delineator of the plate, does away with the outer form of the device completely and diagrams instead the physical pathway of an image through the camera obscura.

“Plate XIX” features eight figures to accompany the text entitled “Of Optics.” Figure 1 illustrates the manner in which light travels through a multiplying glass to the eye. Figure 2 diagrams the optical physics of the portable box camera obscura with a mirror to right the inverted image. Figure 3 illustrates the physics of the common looking glass. Figure 4 explains the optical illusion of reduced proportion in a looking glass. Figure 5 illustrates the separation of light into the color spectrum through a glass prism. Figure 6 is a diagram of the color spectrum of light on a wheel. Figures 7 and 8 are small geometric diagrams mapping the movement of light rays in the illusion of an arched rainbow.

James Ferguson (1710–1776) was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1763. On April 1, 1764, Ferguson observed the eclipse of the sun from Liverpool, England, about which he wrote a paper for the Royal Society entitled, “Observations on the eclipse of the sun” that same year (P. Rothman, “Ferguson, James” Oxford DNB).

The text in Lectures on Select Subjects was drawn from James Ferguson’s extensive public lectures on a variety of scientific topics. A self-taught scientist and a Fellow of the Royal Society, Ferguson sought to elucidate both his texts and his lectures for easy comprehension by his public. Ferguson said, “I had a view … to avoid all superfluity, and to render everything as plain and intelligible as I thought the subject would admit of” (qtd. in P. Rothman, “Ferguson, James" Oxford DNB). His sentiments align with concurrent popular interests in science as a rational and edifying recreation, exemplified in texts by M. Guyot, William Hooper, and Jacques Ozanam, and by the serial public lectures given by Ferguson, Joseph Priestly, and other natural philosophers. According to Jessica Riskin, these lecturers’ “efforts to amuse were dramatically successful. Fashionable people thronged to see nature’s ways laid bare” in the late eighteenth century (J. Riskin, “Amusing Physics” 43). The intention of this type of public lecture was to be both didactic and amusing, rather than tediously difficult or boring; further, “an insistence on simply seeing permeated the amusing physics curriculum,” an impetus which parallels the copious illustration accompanying this type of text in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (J. Riskin, “Amusing Physics” 45). Ferguson, however, did not shy away from the mathematical complexities of these topics in either his lectures or his texts, nor did he necessarily suggest experiments for the amateur scientist to perform at home. Rather, an understanding of the figures on “Plate XIX” and the associated text from Lectures on Select Subjects requires a high level of scientific and visual literacy.

In this plate, Ferguson diagrams the path of an image (AB) through the camera obscura: the image moves through the glass lens (CD) and is inverted (GH) and then reflects off the glass mirror (EF) and is righted (JK). The careful attention to the optical physics of the apparatus, rather than its outward appearance or construction—especially when considered with both the repeated printings of the text and the general popularity of Ferguson’s lectures—suggests a more complex engagement with and understanding of optics on the part of the public in the Romantic period. Moreover, the absence of the recognizable physical structure of the camera obscura in the form of a box or room on “Plate XIX” subverts Jonathon Crary’s generalizing contention that the apparatus disembodies and interiorizes vision (J. Crary, Techniques of the Observer 39). Without the structure of the camera obscura apparatus in which to obscure oneself, the optical physics of the device supersede any potential effects of disembodiment or interiorization of vision.

Locations Description

The Royal Society of London.

Collection

Accession Number

Thordarson T 1061

Additional Information

Bibliography

Crary, Jonathan. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990.

Ferguson, James. Lectures on Select Subjects in Mechanics, Pneumatics, Hydrostatics, and Optics with the Use of Globes, The Art of Dialing, and The Calculation of the Mean Times of New and Full Moons and Eclipses. London: Printed for A. Millar, 1764.

Riskin, Jessica. “Amusing Physics.” Science and Spectacle in the European Enlightenment. Ed. Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent and Christine Blondel. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2008. 43-64.

Rothman, Patricia. “By 'The Light of His Own Mind': The Story of James Ferguson, Astronomer.” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, 54.1 (Jan., 2000): 33-45.

---. “Ferguson, James (1710–1776).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Online ed. Ed. Lawrence Goldman. Oct. 2007. 19 Mar. 2009 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/9320.

Stafford, Barbara Maria. Artful Science: Enlightenment, Entertainment, and the Eclipse of Visual Education. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994.

--- . “Revealing Technologies/Magical Domains.” Devices of Wonder: From the World in a Box to Images on a Screen. Ed. Barbara Maria Stafford and Frances Terpak. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2001. 1-115.