Exhibit

Creation Date

1805

Height

24 cm

Width

35 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

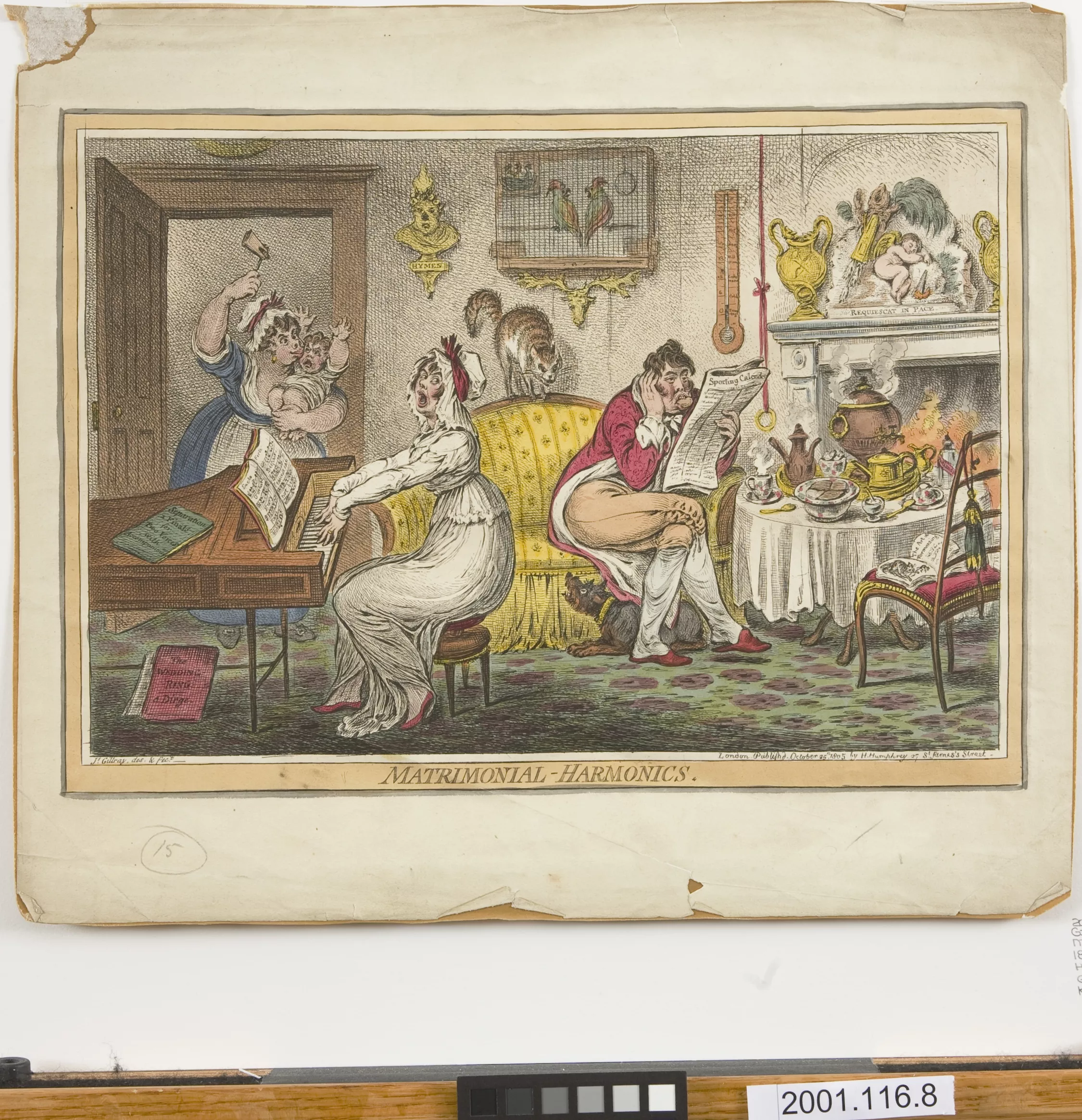

This image depicts the failure of harmony in the marriage previously represented (in its partner print) as a harmonious courtship. Harmony is used as a visual pun in each print to convey first, the appealing fantasy of romance, and then the harsh reality of a marriage originating in such a fantasy.

In this etching, a married couple negotiates the shared space of the parlour. The woman is playing the piano and singing of woe and troubles (as evident from the titles of her music book) while the nursemaid takes care of the fussy baby. The woman’s husband sits by the fire next to several steaming, serving bowls; he shields his ears from his wife’s music as he reads the paper. Other symbols of discord clutter the room: caged lovebirds in a painting on the wall, a fighting cat and dog, the unattended breakfast table, the sleeping cupid, a thermometer indicating the cold temperature of the room. This accumulation of broken and discordant images signifies that the incompatability between the husband and wife extends beyond the musical realm.

The domestic unrest in this caricature directly contrasts with the musical and social harmony of its companion piece, Harmony before Matrimony, and serves to highlight several musical and social themes. While the theme might seem like a misogynistic critique of the wife—whose inadequate musical skills, once employed to court, are useless and isolating in a marriage—I argue that Gillray is actually critiquing the system that produces such a woman, not the woman herself. By expecting women of upper middle class and wealthy families to be well-cultured individuals, and then limiting that culture to less-than-useful realms and subjects, it is society itself which creates the inharmonious structure we see depicted here. The husband, though acting irritated, is complicit in this system. His retreat behind the newspaper is an evasive gesture designed to reject any responsibility for the situation, but the viewer knows otherwise: it takes both a cat and a dog to fight. As representatives of a flawed social system which, contrary to the more holistic philosophies of the Romantics, retreats into minutiae and tedium, this husband and wife ask the viewer to rethink his or her own adherence to social harmony. This depiction of the couple argues, I think, for a broader system of education for women that would equip them with an understanding of both harmony and the system of harmonics that produces this harmony (both literally and metaphorically).

An etiquette book published in 1798 by Maria Edgeworth entitled Practical Education also attacks the social practice of educating “daughters musically for the marriage market, displaying them at social gatherings in order to attract husbands for them” (A. Clapp-Itnyre Angelic airs, Subversive songs 32). Edgeworth writes that not only does this musical education fail to set young women apart now that all young women are expected to be musically inclined, but that the technique is useless because the men it attracts are “not particularly calculated to make good husbands” (M. Edgeworth Practical Education 368). Edgeworth argues this because the men who would be attracted to a woman performing in public would invariably be attracted to her for the wrong reasons—not for her artistry or accomplishment, but for her physical attributes thus on display. The highest good a woman’s music could achieve in Edgeworth’s eyes would be helping her to pass the time in her own home or among friends; to be out in public as a performer cheapens her. Music should be a private act that is not tainted by the sexual suggestiveness of the public, professional sphere.

Interestingly, however, Gillray’s woman and man ostensibly have begun their courtship in private; their only audience as they court is their pets. This companion sketch similarly depicts them at home; the wife is quite genteel and does not perform for anyone other than herself and her unwilling household. However, Gillray is still indicating something problematic with this structure, and this indication may be in partial disagreement with Edgeworth’s philosophy. Given the caged birds in this second etching, he could be arguing that it would be better if the “caged bird," the wife, were able to sing and perform in public. However, it is also made clear to the viewer that the wife is not a very good musician. Again, this seems to support a reading where Gillray uses the trope of musical courtship to incite the viewer to question the social system—a system which educates women to attract men through artifice and useless skills that do not facilitate better relations between the sexes. Even worse, with the presence of the baby (perhaps a girl?) by the piano, Gillray suggests that this cycle may continue, confining women to socially prescribed roles and limiting any kind of real dialogue and harmony between men and women.

Locations Description

Gillray completed the caricatures at his lodgings with his publisher on St. James’s Street.

Accession Number

2001.116.8

Additional Information

Bibliography

Clapp-Itnyre, Alisa. Angelic Airs, Subversive Songs: Music as Social Discourse in the Victorian Novel. Athens: Ohio University Press. 2002.

Edgeworth, Maria, and Richard Lovell Edgeworth. Practical Education. 1798. New York: Harper and Bros. 1835.

Harmonics, or the Analogy of Sound. Musical World, 12:85 (1839:Aug.) p.238.

Ritchie, Leslie. Women Writing Music in Late Eighteenth Century England. Ashgate: 2008.