Creation Date

1775

Height

16 cm

Width

11 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

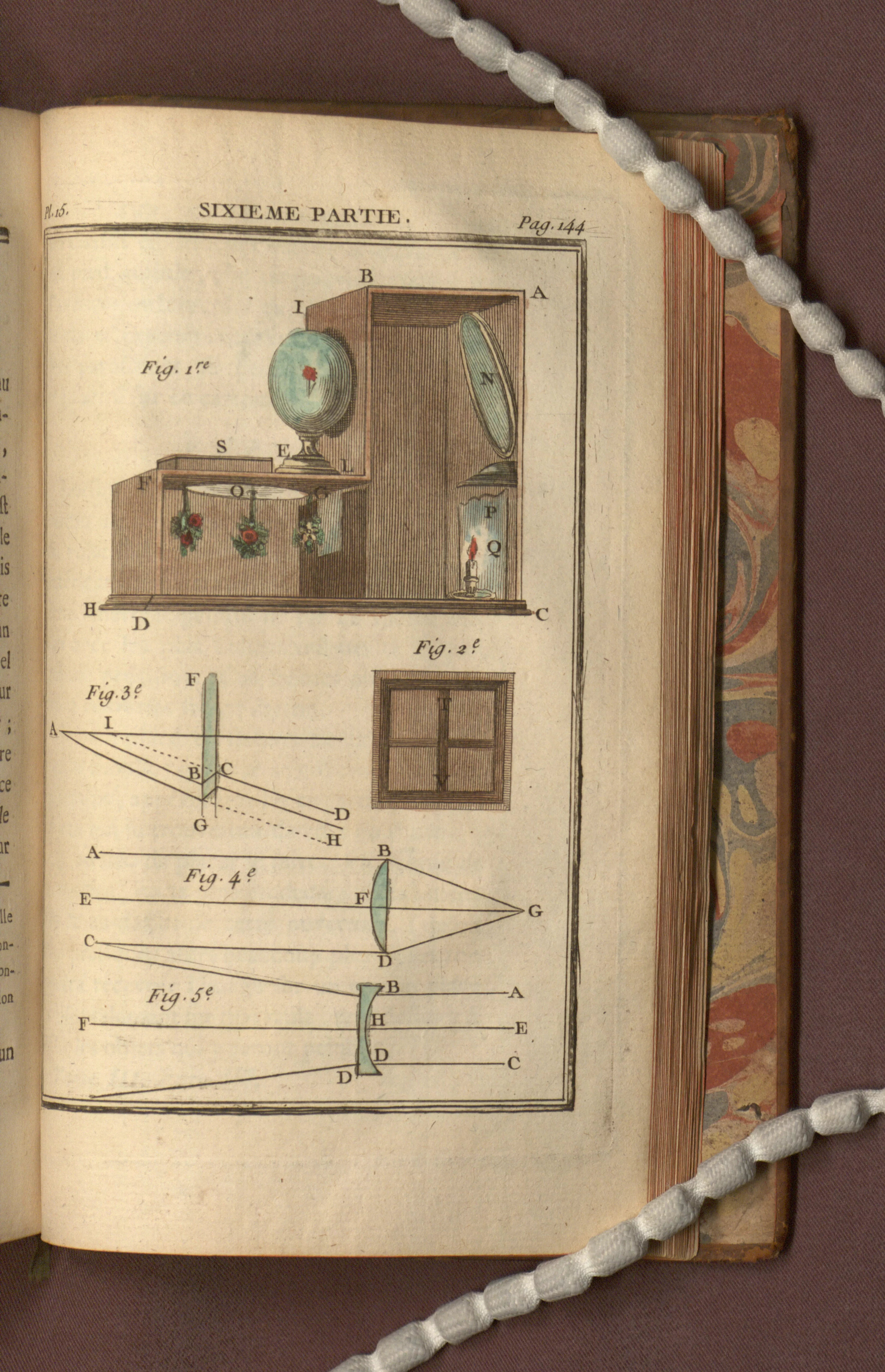

“Plate 15” from Nouvelles recreations exemplifies the dual purpose of many scientific recreation texts: to explain the physical science in question and to instruct the reader on how to easily recreate and perform scientific experiments. The illusion involving catoptrical mirrors explicated by Guyot’s text is illustrated not only with a clear image of the constructed device but also by geometric diagrams of the reflection of light on the concave and convex mirror surfaces. While not illustrative of the camera obscura apparatus as such, this plate suggests another type of optical device included in discussions of the susceptibility of vision to illusions and tricks despite its foregrounding in optical physics.

These five figures explicate the construction of a device which, using catoptrical mirrors, project optical illusions. Figures 1 and 2 portray the device itself, while Figures 3 through 5 explain the optical physics of the convex and concave mirrors and the reflected rays of light involved in the illusion.

The Encyclopedia Britannica was published in Edinburgh in 1771, one year before Nouvelles récréations, and Diderot’s Encyclopédie, initially published in 1751, went into its fifth edition.

M. Guyot’s sensuously hand-colored plates “offered a tantalizing array of apparatuses unfolding a succession of diverting appearances” for the late eighteenth-century amateur science enthusiast (B. Stafford, Artful Science 56). Aligned with the visual strategies and edifying aims of other rational recreations books, Guyot’s text, a French language example of the genre, again pairs the natural science of optics with instruments designed to create fantastic optical illusions and tricks, like the catoptrical mirrors, the magic lantern, and anamorphic images. As noted by Stafford, Guyot believed that despite the hard science behind them, these sorts of optical experiments and devices “demonstrated that, of all the senses, sight was the most prone to illusions,” no matter whether the historical context was one of rational enlightenment or subjective romanticism (B. Stafford, Artful Science 56). The ability to distinguish between the illusory and the real became one of the chief educational purposes of this type of rational recreations texts in the Romantic period (H. Groth, “Domestic Phantasmagoria” 161).

Locations Description

M. Guyot was a member of the Académie des Sciences and the Société Littéraire et Militaire de Basançon.

Collection

Accession Number

Q164 G97

Additional Information

Bibliography

Blom, Philipp. Enlightening the World: Encyclopédie, The Book that Changed the Course of History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Crary, Jonathan. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990.

Darton, Robert. The Business of Enlightenment: A Publishing History of the Encyclopédie, 1775-1800. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979.

Groth, Helen. “Domestic Phantasmagoria: The Victorian Literary Domestic and Experimental Visuality.” South Atlantic Quarterly 108.1 (Winter 2009): 147-169.

Guyot, M. (probably Edme Gilles Guyot). Nouvelles récréations physiques et mathématiques. Paris: Chez l’Auteur and Chez Gueffier, 1772-1775.

Riskin, Jessica. “Amusing Physics.” Science and Spectacle in the European Enlightenment. Ed. Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent and Christine Blondel. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2008. 43-64.

Stafford, Barbara Maria. Artful Science: Enlightenment, Entertainment, and the Eclipse of Visual Education. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994.

--- . “Revealing Technologies/Magical Domains.” Devices of Wonder: From the World in a Box to Images on a Screen. Ed. Barbara Maria Stafford and Frances Terpak. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2001. 1-115.

Warner, Marina. “Camera Ludica.” Eyes, Lies and Illusions: The Art of Deception. Ed. Laurent Mannoni, Werner Nekes, and Marina Warner. London: Hayward Gallery/Lund Humphries, 2004. 13-23.