Creation Date

c.1822

Height

263.5 cm

Width

202.9 cm

Medium

Description

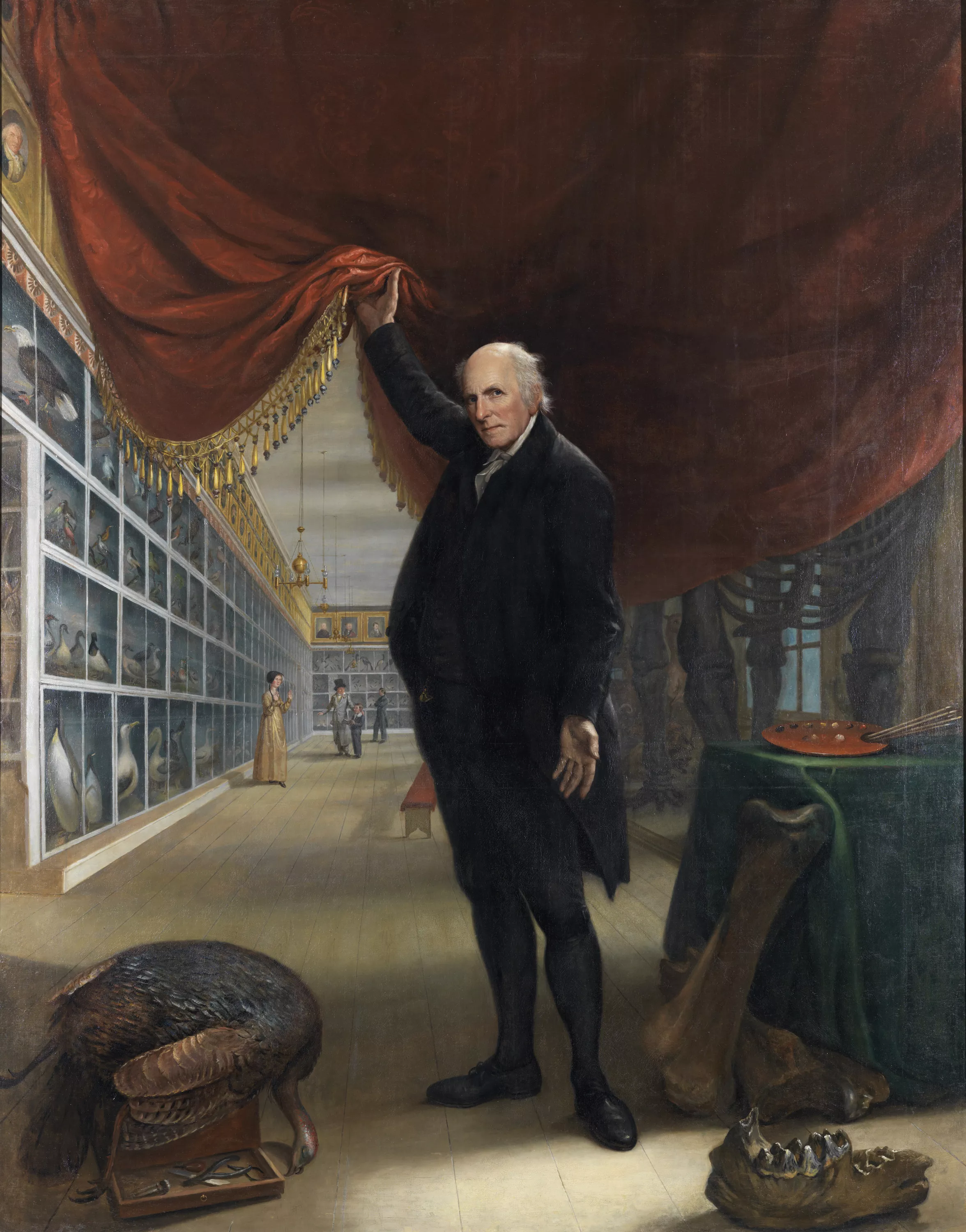

In this self-portrait, artist and curator Charles Willson Peale depicts himself lifting a gold-fringed red curtain to reveal his museum, while inviting the viewer to come forward and enter. The hall behind him is on the second floor of Philadelphia’s Independence Hall, known from 1802 to 1854 as Peale’s American Museum. Peale was granted use of Independence Hall after an unsuccessful attempt to secure federal funding to build his own museum. His collection would remain (and grow) here for 52 years, until it was dispersed via auction. The building, now a UNESCO world heritage site, is where the Declaration of Independence was debated, drafted, and signed.

The portion of the hall visible behind the curtain is the Long Room, a 100-foot space where the majority of the specimens could be found, with shelves containing taxidermied animals, fossils, rare minerals, Indigenous artifacts, or exotic plants. Although it is difficult to discern in the painting due to its perspective, each shelf also contains a diorama with its own hand-painted backdrop—a facsimile of the “environment” in which each specimen would have originally been found (in this, Peale anticipated features of William Bullock’s visual displays). Above these shelves are portraits of “the heroes of the new country” (pafa.org), figures who were instrumental in securing America’s independence. In the foreground, at Peale’s feet, is a dead turkey on a taxidermist’s tool chest—a specimen his son Titian had acquired on an expedition to Missouri—and the bones of the mastodon Peale himself exhumed in upstate New York (see Stein 143–61). On his left, a painter’s palette sits on a small table covered in green drapery. At the far end of the hall, there are four visitors: at the very back a man regards the exhibits; in front of him, a father and child traverse the hall towards Peale; and, in the mid-ground, a lady in Quaker dress observes the mastodon with apparent awe.

This painting was commissioned in 1822 by the museum’s trustees, who specifically requested a full-length portrait that exemplified the founding ideals of the museum (Stein 142). This makes The Artist in His Museum, described by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts as “part advertisement, part philosophical statement,” a unique composition. Unlike earlier self-portraits, in which Peale presented himself as a scientist, artist, or museum impresario, here he is all of the above: a figure conveying mastery in several disciplines. He was, moreover, a founding member of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the National Academy of Design, and he is believed to be one of the first artists to have produced lithographs (winterthur.org). Of this self-portrait (which was his last), Peale himself stated that he desired to "not only make it a lasting monument of my art as a Painter, but also that the design should be expressive, that I bring forth into public view, the beauties of Nature and Art, the rise & progress of the Museum" (Miller 622–3).

In the painting, Peale makes effective use of space, perspective, and props (for example, the painter’s palate) to communicate the depth of his accomplishments in art, science, and technology. As the Metropolitan Museum of Art phrases it, “intelligence, a capacity for piercing observation and a strong will are the traits that emerge most strongly from this self-portrait” (libmma.org). The collection, as it stretches away towards the distant background, is implicitly unlimited, promising fascinating (and educating) encounters with the material and natural world. The museumgoers visible in the background provide a sense of scale, illustrating the breadth, height, and depth of the space. However, this representation of the Long Room is not entirely accurate. We know from other depictions that the right-hand side of the room, like the left, was lined with shelves and cabinets. Peale has replaced these with the mastodon skeleton which he teasingly obscures with the semi-raised curtain (Stein 143). He presents himself as the gatekeeper of these attractions, positioned at the threshold of this enticing and wondrous world.

Given that Peale was well-versed in the scientific literature of his time, it comes as no surprise that he would arrange his specimens according to Linnaean taxonomy (in fact, one of his four sons was named Linnaeus). In the museum, flora and fauna were grouped according to the levels of taxonomic strata they shared; however, he arranged his specimens according to the then-popular belief that every natural object, specimen, and living organism occupies a predetermined place in a cosmic hierarchy known as the “Great Chain of Being.” For example, occupying the highest row of shelves are specimens that pertain to the “highest” order of life, such as taxidermied birds and mammals. Each subsequent row of shelves, in a descending order, contain families of specimens that are less complex, such as fossils of archaic creatures or coral material. Peale's portraits of American patriots—large-scale paintings of famous founding fathers, produced by Peale himself, that line the upper portion of the walls—are positioned above all other exhibits because these figures occupy the top of the “Great Chain.” It has been reported, however, that he considered displaying embalmed corpses before this more practical solution was suggested (Hart and Ward 394).

It is notable that Peale’s museum was free and open to the general public; the exhibits were labeled and the printed guide to the museum was freely distributed (Hart and Ward 396-7). Since the museum was conceived as a service to the nation (as well as an expression of Peale’s keen interests), accessibility was emphasized, in the conviction that better-educated people would become more virtuous and responsible citizens. Contributing to the education of his community—both within Philadelphia and the nation—was one of the ways in which Peale “continually strove to improve the civic and artistic life of both his adopted city and the young republic” (pafa.org). It is also important to recognize the models from which he drew inspiration for this forward-looking enterprise: as a young artist he had spent two years abroad, studying with Benjamin West, and absorbing the techniques of English “grand manner portraiture” (Brooks 32). The museum, “the product of a union between rather conservative English art theory and the radical French Enlightenment,” was a composite expression of his personal, and political values (36). Peale’s final self-portrait captures his pioneering spirit, while enabling us to situate his museum in conversation with the other museum interiors featured in this exhibit, some of which he visited while traveling in Europe. Reflecting on those museums in his Discourse Introductory to a Course of Lectures on the Science of Nature, Peale makes particular mention of the “magnificent” British Museum, and of Lever’s “superb” collection, which—partly for its greater ease of access—he praises as “highly useful, instructive, and amusing” (20–1).

Associated Persons

Copyright

© 2019 Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, All Rights Reserved.

Collection

Accession Number

1878.1.2

Bibliography

Anon. “Charles Willson Peale and His World.” Thomas J. Watson Library Digital Collections, Metmuseum.org.

———. “Charles Willson Peale, ‘The Artist in His Museum’ (1822).” PAFA – Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. www.pafa.org.

———. “Mr. and Mrs. Alexander Robinson.” Reynolda House Museum of American Art, www.reynoldahouse.org.

———. Peale Family Collection 396, The Winterthur Library, findingaid.winterthur.org/html/HTML_Finding_Aids/COL0396.html

———. “Admission Ticket to Peale's Museum.” Philadelphia Museum of Art, www.philamuseum.org

Brooks, Christopher. “Charles Willson Peale: Painting and Natural History in Eighteenth-Century North America.” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 5, no. 1, 1982, pp. 31–9.

Chambers, Richard. “Observations on the Humming-Bird.” Magazine of Natural History and Journal of Zoology, Botany, Mineralogy, Geology, and Meteorology, vol. I, no. 11, 1837.

Hart, Sidney and David C. Ward. “The Waning of an Enlightenment Ideal: Charles Willson Peale's Philadelphia Museum, 1790-1820”. Journal of the Early Republic, vol. 8, no. 4, 1988, pp. 389–418.

Miller, Lillian B. "Charles Willson Peale." International Dictionary of Art and Artists, vol. 2, edited by James Vinson, St. James Press, 1990, pp. 622–3.

Peale, Charles Willson et al. A Scientific and Descriptive Catalogue of Peale’s Museum, by C.W. Peale, Member of the American Philosophical Society, and A.M.F.J. Beauvois, Member of the Society of Arts and Sciences of St. Domingo; of the American Philosophical Society; and Correspondent to the Museum of Natural History at Paris. Printed by Samuel H. Smith, 1796.

———. Discourse Introductory to a Course of Lectures on the Science of Nature; With Original Music Composed for and Sung on the Occasion. Delivered in the Hall of the Universiy [Sic] of Pennsylvania Nov. 8 1800. Printed by Zachariah Poulson Jr., 1800.

Peale’s Museum (Philadelphia Pa). Historical Catalogue of the Paintings in the Philadelphia Museum: Consisting Chiefly of Portraits of Revolutionary Patriots and Other Distinguished Characters. 1813.

Stein, Roger B. "Charles Willson Peale's Expressive Design: The Artist in His Museum." Prospects, vol. 6, 1981, pp. 139–85.

Peale’s American Museum © 2024 by Sophie Thomas, Rhys Jeurgensen, Erin McCurdy, and Romantic Circles is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0