Creation Date

1803

Height

22 cm

Width

14 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

Recreations in Mathematics and Natural Philosophy is an example of the popularization of rational recreations texts in the Romantic period, particularly for use in the home. It explains how to create optical instruments and understand their effects on recreational scientific experiments. The ability not only to enjoy the illusions produced by camera obscuras, magic lanterns, and other optical devices, but, importantly, to distinguish the illusory from the real was paramount to the rational recreations agenda. The camera obscura shown here is a portable device, which increases the range of amusing recreations possible to perform with it in and around the home.

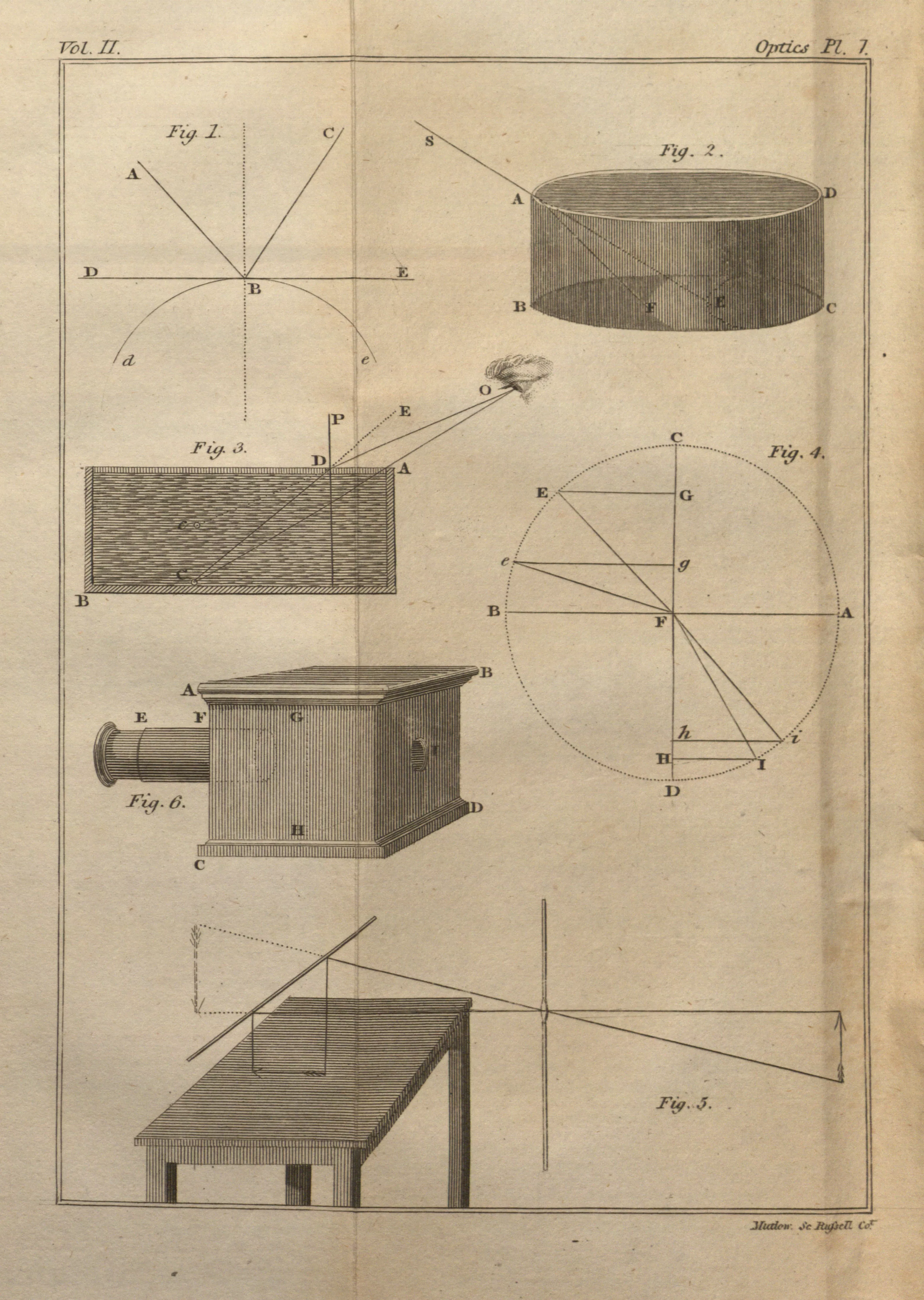

“Plate I” has six figures which illustrate experiments and problems on the nature of light. Figure 1 is a diagram of light reflecting off a polished surface. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate light refraction through water or oil, which is also diagrammed geometrically in Figure 4. Figure 5 demonstrates the inversion of an image of an external object through a lens in a darkened room, or a diagram of how light travels through a camera obscura. Figure 6 is an illustration of a portable camera obscura, the basic construction and uses of which are explicated in the text.

Charles Hutton, LL.D. and F.R.S. (1737–1823), British, received the Copley Medal from the Royal Society of London in 1778 for his papers on the physics of velocity. He resigned from the Royal Society in 1784 over a dispute about the role of mathematics in the organization.

As discussed by Barbara Maria Stafford, Hutton’s translated text aligns with the increased interest in rational recreations, popular leisure pursuits which were intended to simultaneously entertain and intellectually edify young people. Recreations in Mathematics and Natural Philosophy is an example of the rapid popularization of these recreational texts in the Romantic period, particularly for use in the domestic space. As noted by Helen Groth, in the nineteenth century the domestic arena “becomes a space of productive labor, where the mind of the child is actively shaped by the rationalizing energies of the family dedicated to the principles of useful knowledge” (H. Groth, “Domestic Phantasmagoria” 161). The ability not only to enjoy the illusions produced by camera obscuras, magic lanterns, and other optical devices, but, importantly, to distinguish the illusory from the real was paramount to the rational recreations agenda. As evidenced in the sustained revision, expansion, and republication of Ozanam’s original work on recreational experiments from the late seventeenth century well into the nineteenth, optical technologies and rational experiments preoccupied the Romantic visual imagination and reinforced the emphasis on edification and self-improvement through efforts at “practical education” in the domestic sphere (H. Groth, “Domestic Phantasmagoria” 161).

“Plate I” of Recreations in Mathematics and Natural Philosophy reinforces the essential function of the text as both amusing and instructive, pairing illustrations of easily constructed optical experiments and technologies, such as the box camera obscura, with geometrical diagrams explaining the movement of light within them. The camera obscura shown on “Plate I” (Figure 6) is a portable device, which increases the range of amusing recreations possible to perform with it in and around the home. Rather than completely isolating and disembodying vision, however (as Jonathan Crary argues), the portable camera obscura, like other optical devices that can easily move with the observer from place to place, becomes a “visual prosthesis,” an extension of the body and the consciousness (M. Warner, “Camera Ludica” 17). Thus, this type of camera obscura functions more like the various modern models of vision discussed by Crary, which have “no reference to a spatial location” and undermine the supposedly “fixed relations of interior/exterior” (J. Crary, Techniques of the Observer 24).

Locations Description

Charles Hutton taught at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, England and was elected a member of the Royal Society of London on June 16, 1773. Jacques Ozanam was elected a member of the Académie des Sciences in 1701.

Collection

Accession Number

CA 8397

Additional Information

Bibliography

Crary, Jonathan. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990.

Groth, Helen. “Domestic Phantasmagoria: The Victorian Literary Domestic and Experimental Visuality.” South Atlantic Quarterly 108.1 (Winter 2009): 147-169.

Guicciardini, Niccolò. “Hutton, Charles (1737–1823).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. 19 Mar. 2009 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/14300.

Hammond, John. H. The Camera Obscura: A Chronicle. Bristol, UK: Adam Hilger, Ltd., 1981.

“Memoir of the Late Dr. Hutton.” Gentleman's Magazine. (March 1823): 228. Access: British Periodicals. ProQuest, L.L.C., 2006-2009. 2 March 2009 http://britishperiodicals.chadwyck.com/.

O'Connor, John J. and Edmund F. Robertson. "Jacques Ozanam." MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive. Ed. John J. O’Connor and Edmund F. Robertson. St. Andrews, Scotland: JOC/EFR August 2005. 19 March 2009 http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Ozanam.htm.

Ozanam, Jacques. Recreations in Mathematics and Natural Philosophy in Four Volumes. 1694. Trans. Charles Hutton. London: Printed for G. Kearsley by T. Davison, 1803.

Stafford, Barbara Maria. Artful Science: Enlightenment, Entertainment, and the Eclipse of Visual Education. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994.

--- . “Revealing Technologies/Magical Domains.” Devices of Wonder: From the World in a Box to Images on a Screen. Ed. Barbara Maria Stafford and Frances Terpak. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2001. 1-115.

Warner, Marina. “Camera Ludica.” Eyes, Lies and Illusions: The Art of Deception. Ed. Laurent Mannoni, Werner Nekes, and Marina Warner. London: Hayward Gallery/Lund Humphries, 2004. 13-23.