Creation Date

c.1835 (after 1786)

Height

40 cm

Width

42.6 cm

Medium

Description

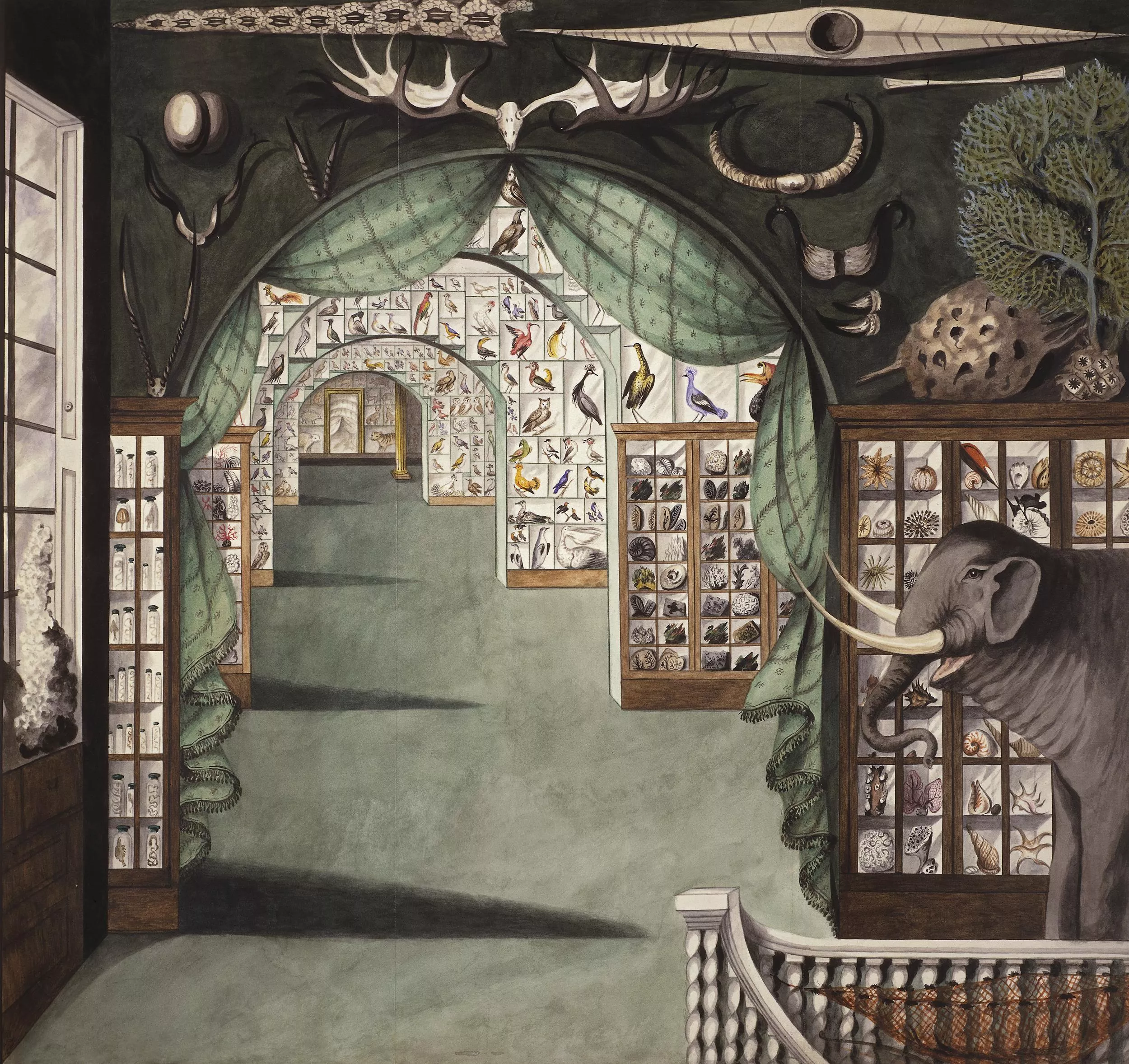

This watercolor, copied ca. 1835 from Sarah Stone’s original—made on site in 1786—depicts Sir Ashton Lever’s museum, or “Holophusicon.” Making effective use of one-point perspective, the drawing depicts the long series of rooms comprising the upper floor of the museum. Stone captured this remarkable view from the “Stair Room,” which was the first stop, aside from the entrance hall, on a museum visitor’s tour through Lever’s collection. Beyond the Stair Room can be seen, in successive order, the Native Fossil Room, the Extraneous Fossil Room, the Shell Room, and the Argus Pheasant Room, each separated by an arch. The museum consisted of seventeen rooms in total.

Immediately to the right, just behind the banister, stands a taxidermied elephant—a silent sentinel welcoming guests to the collection. The walls display a number of prized artifacts such as the “Greenland Kayak” (top right), and several sets of horns and antlers belonging to a variety of large mammals from Europe, Asia, Africa, and North America. A large piece of coral sits on the windowsill (on the left), and an additional set of equally large coral pieces, of several different species, sit atop the set of cases on the right. Contained in these cases is a variety of shells, preserved invertebrate specimens, and other preparations. Despite their quite specific names, the rooms contained a diverse mixture of specimens. The display cases that are visible contain visually pleasing arrangements of shells, fossils, corals, and species from the crustacean, mammal, and reptile classes. Because ornithology was one of Lever’s dominant passions, most of the visible cases contain taxidermied birds. Many of these ornithological specimens passed between Hunter and Lever as they studied the finer points of anatomy (Barrington 169).

Sarah Stone began drawing and painting the contents of the Holophusicon in 1777, two years after the museum opened, and over the next nine years she completed well over a thousand illustrations (see Force and Force). The practice of sketching the specimens in museums and copying the notable artwork in galleries was well established by the eighteenth century, but Stone’s illustrations were not just the product of a genteel pastime: the Holophusicon displayed her work in its exhibits. In 1784, Lever advertised in the Morning Post and Daily Advertiser an exhibition of “transparent Drawings in Water Colours, from the most curious specimens in the Collection, consisting of above one thousand different articles, executed by Miss Stone, a young lady, who is allowed by all Artists to have succeeded in the effort beyond all Imagination” (19 January 1784).

The image communicates the affective nature of the museum’s vastness and complexity, which is also conveyed by museum’s name: Lever decided, once installed in Leicester House, to call it the “Holophusicon” (which means, literally, nature in its entirety). The somewhat unregimented system of arrangement evident in the image—and in the accounts of visitors—reflects the fact that, like Renaissance wonder cabinets, relations between the Holophusicon’s objects were less important than their overall effect. Being confronted by such an eclectic display, a visitor to the museum (and the viewer of the watercolor depicting it) “looks at the vast volumes of actual information, that everywhere surround him, and is indeterminate where to begin, or on which to fix his attention most” (Anon. 18-21). The image deftly captures the visual cacophony created by placing many diverse plant and animal specimens together in the same rooms. The motivation for this was in large part aesthetic: the juxtaposition of birds and fossils would “give rise to visual pleasure from the contrasts between the soft, often highly-coloured feathers of the birds and the hard textures and brown-grey tones of the fossils” (Haynes 7).

Despite the fact that such a scene resists easy scientific interpretation, the system of arrangement was meant to represent “nature inside the museum as it was outside it: full of wonder, all encompassing, engulfing, dazzling and confusing, but ultimately something from which understanding could be generated” (Haynes 10). Lever was driven by a desire to replicate rather than anatomize the world as it appears, and thus his curatorial techniques, while different from those of contemporary natural history museums, still engaged in “pursuits calculated to enlarge the bounds of science, and diffuse knowledge” (Sewell 83). The dense yet segregated arrangement of Lever’s collection alludes to deeper (theological) mechanisms of the natural world in the same way that modern museums allude to evolutionary or genealogical history.

The theme of “discordant holism” that dominates Lever’s gallery is facilitated by the architectural layout of Leicester House. The perspective from which Sarah Stone created the original image emphasizes both the clear demarcation of the museum into distinct rooms and the unifying thread that connects these rooms (i.e., the recurrence of certain types of species, such as birds). In this way, Stone builds into her image the seemingly contradictory themes of division and unity, and of design and chance.

The majority of the South Pacific material (i.e., corals, fossils, Indigenous weaponry) came directly from James Cook, whose seminal voyages resulted in the creation of the “Sandwich Isles Room” on the museum’s ground floor. The Holophusicon’s emphasis on South Pacific material helped establish ethnography as a viable scientific pursuit, for Lever endorsed the idea that the aesthetic and socio-historical significance of “exotic” material extended beyond its curiosity value.

Because Sarah Stone’s drawing captured Lever’s collection as it appeared right before it left his possession, it represents his museum at the height of his curatorial career. Lever’s voracious collecting led ultimately to his financial ruin, and he was forced to sell the collection (which he did by lottery in 1786—it passed into the hands of James Parkinson, who moved the museum to the south bank of the Thames at Blackfriars Bridge, retaining the name Leverian Museum). In spite of this unfortunate turn of events (Lever died two years later in 1788), he had created one of the major natural history collections of the period. By the early 1780s, the collection contained close to 30,000 items, among them many rare specimens, and it attracted visitors in droves. Apart from the British Museum, which could be difficult for the general public to access, “London had never known so extensive a museum of natural history, ethnography, and miscellany” (Altick 29).

Stone’s depiction of the Holophusicon also documents an important phase in the development of natural history as a discipline. Compared to today’s specialized and focused exhibitions, Lever’s collection seems very broad (if not random), but at the time of the Holophusicon’s creation, “natural history as a subject was a large field covering not only all aspects of the natural world, including what we now know as meteorology, geology, zoology and botany, but also the ‘works’ and ‘manners’ of mankind” (Haynes 3). Lever engaged a community of largely gentlemanly practitioners, drawn from the professional and upper classes, who shared information, methods, and artifacts, and whose collections reflected and consolidated their knowledge and influence.

Despite the innovation and popularity of Lever’s collection, the British Parliament was against annexing it in the name of His Majesty’s Government, deciding not to “vote away the money of their constituents for stuffed birds and butterflies” (The Parliamentary Register 175). Parkinson extended the life of the museum at its new location until 1806, after which the collection was dispersed to private museums and collectors (among them, notably, William Bullock), in a sale that lasted over two months. Sarah Stone would go on to draw and paint the (still expanding) collection after it moved to Blackfriars Bridge, but her 1786 watercolor, on which the above image is based, would be the last painting commissioned by Lever. By illustrating, emphasizing, and celebrating the richness and diversity of his collection—from its most dazzling viewpoint—Stone helped to secure for posterity Lever’s status as an accomplished collector and curator, preserving the memory of what was, by all accounts, an extraordinary museum.

Associated Persons

Copyright

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Collection

Accession Number

Am2006,Drg.54

Bibliography

Altick, Richard. The Shows of London. Belknap/Harvard University Press, 1978.

Anon. “A Description of the Holophusicon, or, Sir Ashton Lever’s Museum.” The European Magazine, and London review; containing the literature, history, \politics, arts, manners and amusements of the age, The Philological Society of London, vol. 1, 1782, pp. 17–21.

Barrington, Daines. Miscellanies by the Honourable Daines Barrington. Printed by J. Nichols, 1781.

Force, Roland W. and Maryanne Force. Art and Artifacts of the 18th Century: Objects in the Leverian Museum as Painted by Sarah Stone. Bishop Museum Press, 1968.

Haynes, Clare. “A ‘Natural’ Exhibitioner: Sir Ashton Lever and his Holosphusikon.” British Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 24, 2001, pp. 1–14.

Jackson, Christine E. Sarah Stone: Natural Curiosities from the New World. Merrell Holberton and the Natural History Museum, 1998.

Jefferson Exhibit Collection (Library of Congress). Miscellanies. Printed by J. Nichols Sold by B. White at Horace’s Head Fleet-Street and J. Nichols Red Lion Passage 1781.

Kaeppler, Adrienne. Holophusicon: The Leverian Museum. An Eighteenth-Century English Institution of Science, Curiosity, and Art. ZKF Publishers, 2011.

Kimber, Issac, et al. Gentleman’s Magazine. Vol. 43, May 1773, pp. 219–21.

Leverian Museum (London England) et al. A Companion to the Museum: (Late Sir Ashton Lever’s) Removed to Albion Street the Surry End of Black Friars Bridge. Publisher Not Identified 1790.

McNearney, Allison. "How Sir Ashton Lever Curated the World—Then Lost it all: His Obsession with Collecting Artifacts and Specimens would Eventually Lead to His Financial Ruin. But First He Amassed an Impressive Collection of Curiosities." The Daily Beast, 2018, pp. 1–3.

The Parliament of Great Britain. The Parliamentary register; or, History of the proceedings and debates of the House of Commons; Containing an account of the most interesting speeches and motions; accurate copies of the most remarkable letters and papers; of the most material evidence, petitions, &c. laid before and offered to the House, during the first session of the fifteenth Parliament of Great Britain. Begun to be holden at Westminster on the 31st day of October 1780. Printed for J. Almon and J. Debrett, 1781, pp. 174–5.

Sewell, J. “An Account of Sir Ashton Lever, Knt.” The European Magazine, and London review; containing the literature, history, politics, arts, manners and amusements of the age. The Philological Society of London, vol. 6, 1784, pp. 83–4.

Smith, Charlotte and National Art Library (Great Britain). Dyce Collection. A Natural History of Birds: Intended Chiefly for Young Persons. Printed for J. Johnson St. Paul’s Churchyard, 1807.

Stockdale, Percival. Three Poems: I. Siddons; a Poem. Ii. a Poetical Epistle to Sir Ashton Lever. Iii. an Elegy on the Death of a Young Officer of the Army. Printed for W. Flexney, 1784.

Thomas, Sophie. “Collection, Exhibition and Evolution: The Romantic Museum.” Literature Compass, vol. 13, no.1, 2016, pp. 681–90.

Sir Ashton Lever’s Holophusicon © 2024 by Sophie Thomas, Rhys Jeurgensen, Erin McCurdy, and Romantic Circles is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0