Creation Date

1791

Medium

Genre

Description

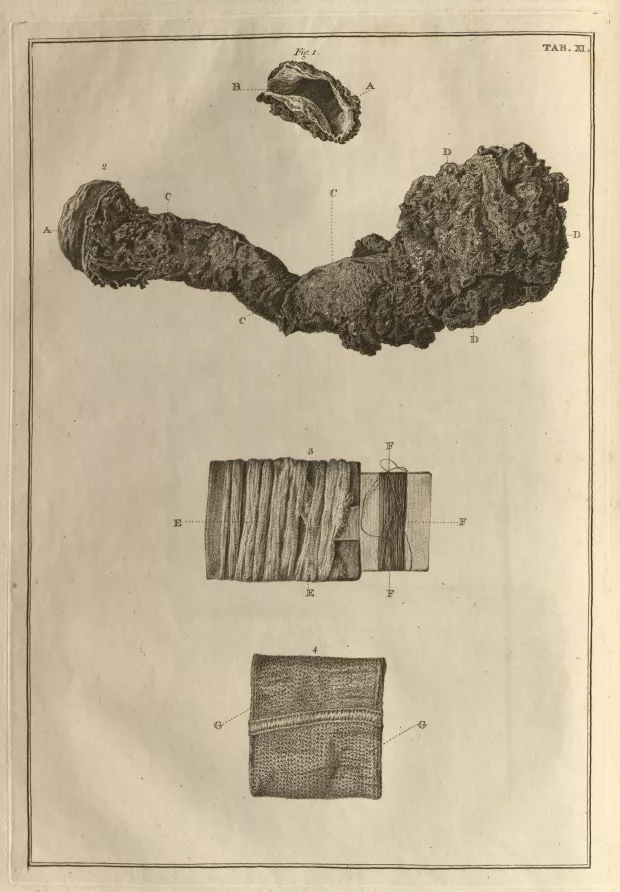

While a number of the Rymsdyks' illustrations in Museum Britannicum are visually sparse in terms of the number of specimens depicted and the scale by which they are rendered, this particular plate is replete with four figures that fill almost all of the available space. The Rymsdyks' work here operates in terms of a unifying characteristic: all four of the objects, two natural and two man-made (or at least formed by human hands), relate to the raw or refined production and manufacture of spider silk. Although both the images of the spider’s nest and the valve are meticulously detailed, their complex and irregular shapes jar with the more familiar figures of the carded thread and the finished product (part of a garter). Many of the Rymsdyks' chosen specimens are rare enough to have defied instant recognition on the part of the reader, but the juxtaposition of the spider’s nest with the thread and garter defamiliarizes it to a greater extent. While the repetition of the tiny, regular stitches in the weave of the garter is almost hypnotic, the grotesque and asymmetric form of the nest is difficult to visually comprehend. However, when all four images are read together with the accompanying text, they represent a distinct progression from natural production to a finished, man-made product.

The Rymsdyks’ association of the natural with the man-made recalls Daston and Park’s characterization of the expansiveness of the early modern Wunderkammern:

Not only did the Wunderkammern display artificialia and naturalia side by side; they featured objects that combined art and nature in form and matter, or that subverted the distinction by making art and nature indistinguishable. These wonders of art and nature juxtaposed, combined, and fused in the cabinets all illustrated an aesthetic of virtuosity. (277)

In his 1762 guide to the British Museum, R. Dodsley seems similarly captivated by the capabilities of insects as the makers of natural wonders:

An Enquiry into this Part of Natural History is very amusing and entertaining, so great is the Variety contained in it; for not only every distinct Class of Insects has a Manner peculiar to itself to preserve and continue the Species, but every distinguished Part of each Class varies in this Particular, yet all of them follow the invariable Law that God and Nature has taught them; assisted by an Instinct, which Man, with all his boasted Reason, cannot with any Propriety account for. (159-60)

Like the Wunderkammern, the Rymsdyks' precise drawings compare and emphasize the skill and technique of both nature and man as maker.

Associated Works

Locations Description

The doors to the British Museum opened to the public in 1759. Although officially founded by an Act of Parliament passed on June 7, 1753, the collections which formed the original content of the museum belonged to three men: Sir Robert Cotton (1570-1631), Robert Harley, Earl of Oxford (1661-1724), and Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753) (Crook 44). Both Sloane, dubbed “the foremost toyman of his time” by the poet Edward Young, and his collection were already famous by the time George II purchased them for the museum in 1753 (Young 97). The new museum, which prominently displayed Sloane’s natural and man-made curiosities, was a success. A review published in the July 1788 issue of The New London Magazine praises the particular merits of the Sloaniana, “which excite in the contemplative mind the most exalted ideas of divine wisdom in the creation of nature, and prove at the same time a striking monument of human industry” (“An Account of the British Museum” 378).

Visitors to the British Museum had to apply in writing for tickets, but, as a public institution maintained by government funds, admission was free. As a reviewer wrote in 1839, “The cheapest by far of our public exhibitions as well as in other respects the best, is the British Museum, for that costs nothing” (“Synopsis” 299). Museum policies limited both the number of visitors and the amount of time they were given to look at the exhibits; in 1762, R. Dodsley recorded the rules as follows: “fifteen Persons are allowed to view it in one Company; the Time allotted is two Hours” (xxii-xxiii). In spite of these limitations, the exhibit rooms were frequently over-crowded and the museum-going experience was often harried:

Among the Numbers whom Curiosity prompted to get a Sight of this Collection, I was of Course one; but the Time allowed to view it was so short, and the Rooms so numerous, that it was impossible, without some Kind of Directory, to form a proper Idea / of the Particulars. (Dodsley xiv)

Eric Gidal notes that the British Museum was unique in this unprecedented degree of access granted to the public: "As an institution founded ‘not only for the inspection and entertainment of the learned and curious, but for the general use and benefit of the public,’ the British Museum marked a union of legitimization and freedom both aesthetic and social" (21). With free admission came crowds, and with those crowds came anxiety regarding who ought to see the collections as well as how they ought to be seen. Over the course of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, the museum continued to gain popularity. By 1805, 12,000 people visited annually. By 1817 that number grew to 40,000, and by 1833 over 210,00 people came each year to see the collections (Goldgar 229-30). As many reviewers noted, large and often raucous crowds were now an inescapable part of the museum-going experience:

[T]he bustling crowds which thrice-a-week are to be seen in the British Museum, swarming with aimless curiosity from room to room, loudly expressing their wonder and disapprobation of the very things most worthy of admiration, or passing with a vacant gaze those precious relics of antiquity, of which it is impossible that they can understand the value as they are, for the most part, insensible to the hallowing associations, which render these objects the links of connexion between distant ages and our own. (“A Visit to the British Museum” 42)

The behavior of these crowds generated considerable anxiety in the press, with one 1839 reviewer even going so far as to publish three “cautions” for visitors to the British Museum and other public exhibitions: “Touch nothing,” “Don’t talk loud,” and “Be not obtrusive” (“Synopsis” 302-3).

Copyright

Copyright 2009, Department of Special Collections, Memorial Library, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI

Collection

Accession Number

Thordarson T 4136

Additional Information

Bibliography

“An Account of the British Museum.” New London Magazine 4.40 (1788): 377-78. Print.

"A Visit to the British Museum." The Court Magazine and Belle Assemblée [afterw.] and Monthly Critic and the Lady's Magazine and Museum. Vol. XV. Oxford: Dobbs, 1839. 42-8. Print.

Crook, J. Mordaunt. The British Museum. London: Penguin, 1972. Print.

Daston, Lorraine and Katherine Park. Wonders and the Order of Nature. New York: Zone, 1998. Print.

Dodsley, R. The General Contents of the British Museum: with Remarks. Serving as a Directory in Viewing that Noble Cabinet. London, 1762. Print.

Goldgar, Anne. “The British Museum and the Visual Representation of Culture in the Eighteenth Century.” Albion 32.2 (2000): 195-231. Print.

Rymsdyk, Jan van and Andreas van Rymsdyk. Museum Britannicum, Or, A Display In Thirty Two Plates, In Antiquities and Natural Curiosities, In That Noble and Magnificent Cabinet, the British Museum: After the Original Designs From Nature. 2nd ed. London, 1791. Print.

“Synopsis of the Contents of the British Museum” Eclectic Review 6 (1839): 281-306. Print.

Thornton, John L. John Van Rymsdyk: Medical Artist of the Eighteenth Century. New York: Oleander, 1982. Print.

Young, Edward. The Poetical Works of Edward Young. Cambridge, 1859. Print.