Exhibit

Creation Date

1830

Height

29 cm

Width

21 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

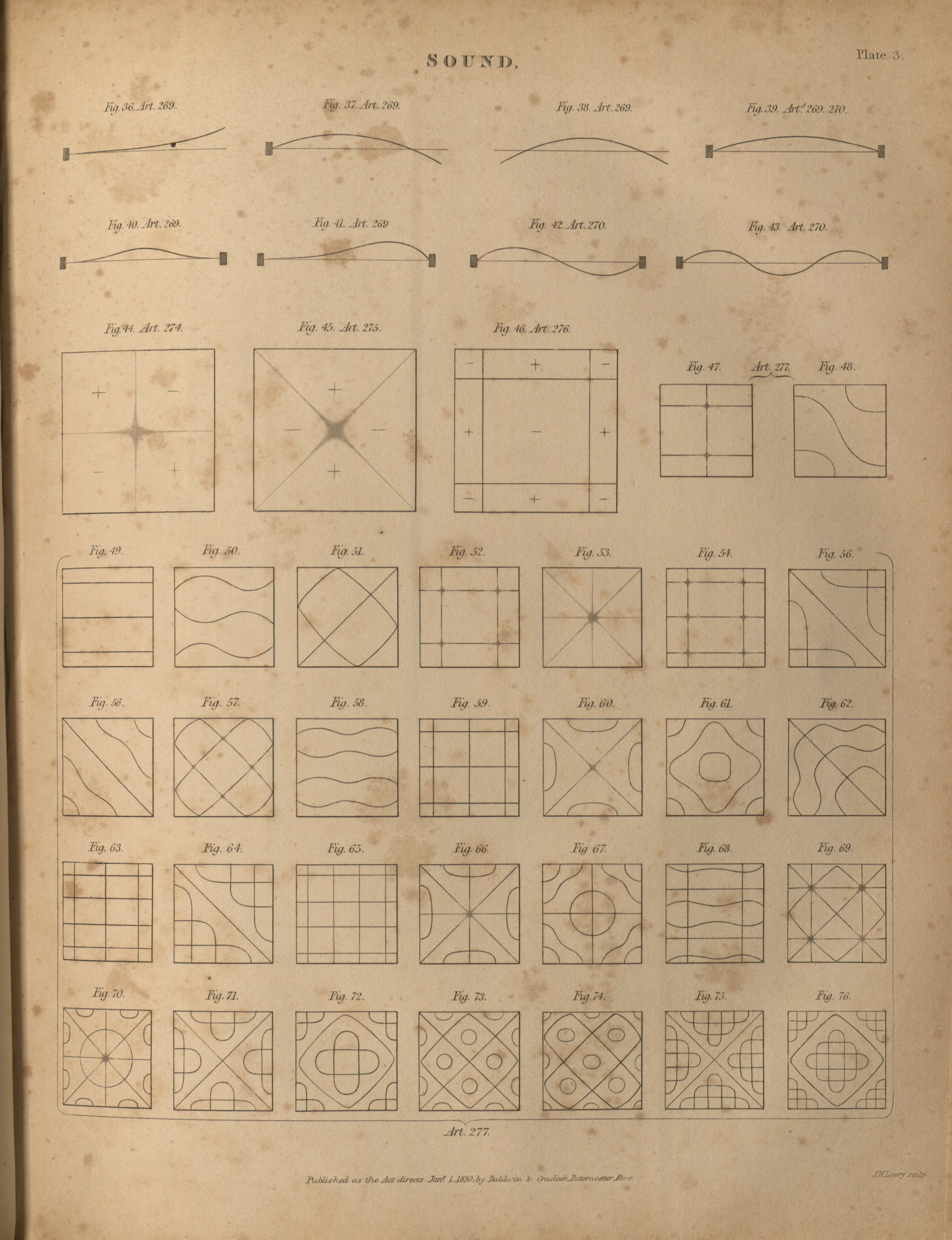

This scientific diagrams depicts "vibrations in solid bodies," including rods and plates. In the image, Herschel presents readers with another set of experiments that helps them conceptualize the movement of sound through space, again depending on the visual. Figures 36-41 involve the vibrations of a rod either resting against a wall or free. Even more interesting are figures 42-46; these illustrations depict “vibrations in plates of metal,” and show the movement of sand on a plate being vibrated with a bow. Herschel writes that the sand is “thrown away from the vibrating parts" and accumulates "on those at rest." The succeeding figures are the same experiments applied to circular, as opposed to square, sheets of metal.

This image marks yet another way to conceptualize the aural through visual means. Sound becomes embodied, made visible in the varied and beautiful patterns produced by the motion of its waves through sheets of metal; if sound can be said to have a character—such as that ascribed to the Aeolian harp by Romantic poets and philosophers—then Herschel provides us with an elegant depiction of the aesthetic quality of that character. The patterns are symmetrical, balanced, and intriguing. While the primary objective of these engravings is ostensibly scientific (given the context and content of the text they accompany), they also fulfill the surreptitious function of aestheticzing sound: by making sound visible, the engravings ask the observer to reconceive the sounds that reach his or her own ears in a particular, aesthetic way.

Herschel’s experiments are modeled on those of Ernst Florens Freidrich Chladni, who announced his discovery of “sand figures” in 1785. These figures led to observations by the Romantic physicist Johann Wilhelm Ritter:

[Ritter] held the opinion that material images, like Chladni’s figures, entailed the true language—a pictorial language—of science . . . While the mathematical approach to sound was by no means excised, it was this respect for the image and the attitude that pictures could give meaningful signs of phenomena that excited the Naturphilosophen. (Hankins and Silverman 132)

The "Naturphilosophen" (Hankins and Silverman are referring specifically to Julius Robert von Mayer, Hans Christian Oersted, and Lorenz Oken) searched for these symmetries as “signs of hidden relationships among natural forces” (Hankins and Silverman 132). As a result, the sand figures also raised questions about the potential intersections of myriad areas that are kept separate in 20th- and 21st-century scientific inquiry. Influenced by theories of magic from the seventeenth century, and navigating the developing fields of science, natural philosophy, acoustics, and music, these men sought an overarching narrative from which to derive meaning (Hankins and Silverman)

The aural aspect of this narrative was continually supplemented by the rhetoric of sight. Men like Herschel, and in the following passage, the reviewers of his text, consistently used visual analogies to explain aural phenomena:

[N]ow it is a singular fact that these colors, red and green, are harmonic colors, or such as always harmonize together in painting; and they have, besides, another property in forming white light when they are mixed together. In like manner, the harmonic color of blue is orange, and that of yellow, violet. The retina of the human eye, therefore, is, by the action of one color, thrown into such a state of vibration, as to see at the same time its harmonic color. ("ART" 493)

In order for the reader to understand harmonics in terms of what we hear, these writers have determined that the harmonics of what we see will provide the easiest parallel. In this case, they go on to describe the way in which one may look at a square of blue, and yet, when looking away, see a red square instead. These ghost colors are a fitting representation of musical harmony: both colors and harmonics are invisible supplements to what either the eye or ear, respectively, is actually sensing. Born out of resonance and vibration, this confluence of sight and sound buttressed an eighteenth-century and early nineteenth-century understanding of the shared, invisible aspects of sight and sound.

Accession Number

QC 3 G4

Additional Information

Bibliography

"ART. VI.-A Treatise on Sound." The Quarterly Review 44.88 (1831): 475-512. Print.

Ferguson, W.T. Sir John Herschel and Education at the Cape 1834-1840. Cape Town: Oxford UP, 1961. Print.

Hankins, Thomas, and Robert Silverman. Instruments and the Imagination. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1995. Print.

Barlow, Peter and John F. W. Herschel. The Encyclopaedia of Mechanical Philosophy: Comprising the Sciences of Mechanics, Hydrodynamics, Pneumatics, and Optics. London: J. J. Griffin, 1848. Print.

“Joseph Wilson Lowry, F.R.G.S." Nature 20.504 (1879): 197-198. Print.