Exhibit

Creation Date

1839

Height

6 cm

Width

5 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

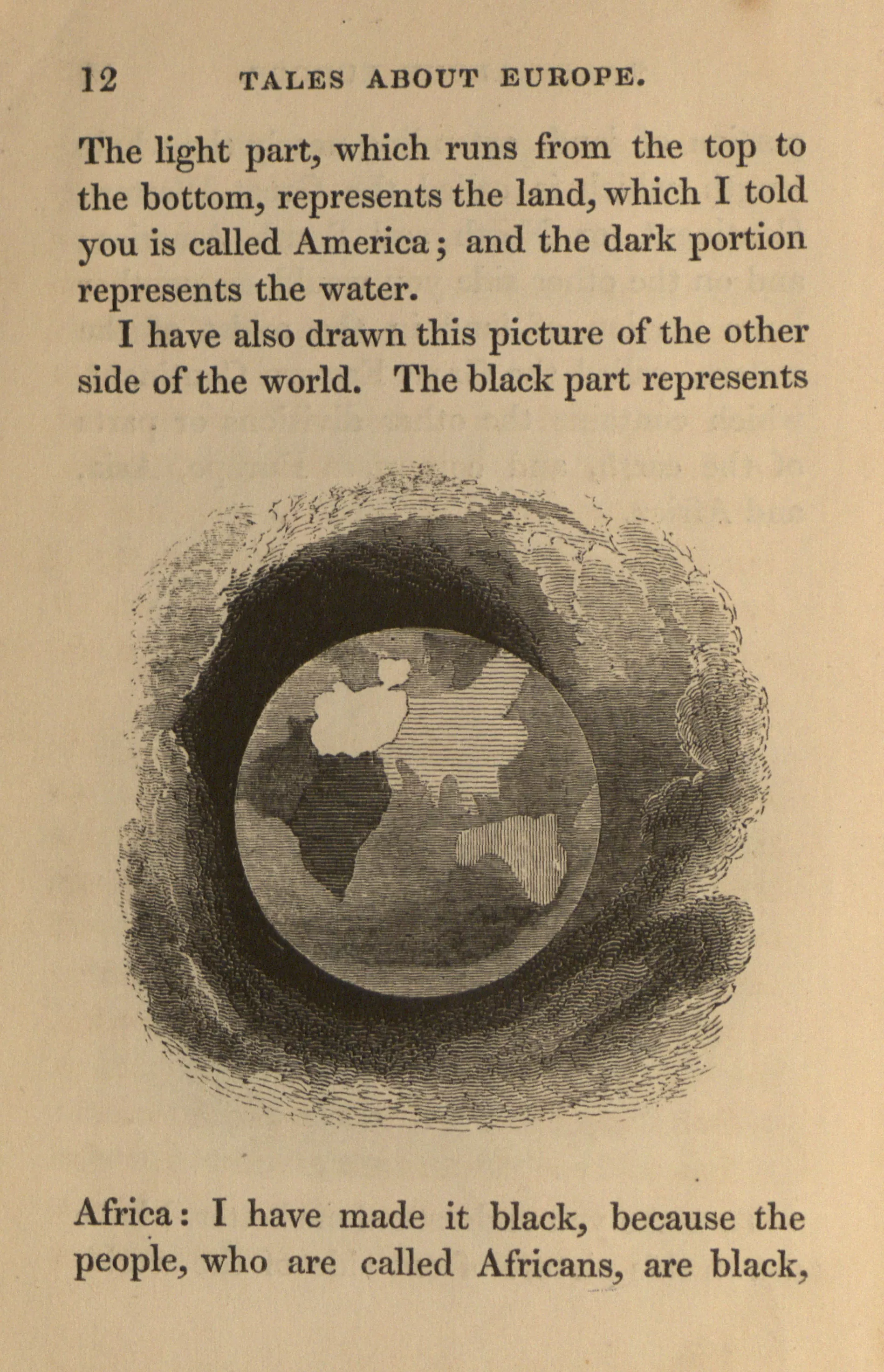

This rendering of Earth seems to depict each visible continent as the same "shade" of skin stereotypically used to describe its inhabitants. Consequently, this illustration serves as an example of the attempt to inculcate children with both a knowledge of the world and the proper perspective with which to view that world.

This illustration depicts a rough image of Earth, which is shown floating in black space that grows misty near the edges. Europe is white, while everything "east," as well as Australia, is colored a lighter grey; Africa is entirely black. Neither the Americas nor Great Britain are shown.

Combining an educational view of the globe with a common racial stereotype of Africa, this image shows that English publishers (and presumably parents) were willing to embrace American-made texts and illustrations for their children as long as they ascribed to the same set of prevailing philosophies as English authors. Hannah More was both an influence on and a proponent of Parley’s books, finding in them an appropriate balance between worldly instruction and protective moral constraints (Butts 154). This particular image, though simple, encompasses this tentative acceptance of transatlantic children’s material perfectly—it teaches children both what the world looks like and how they are to look at it. The image itself (taken apart from the accompanying text) indicates the extent to which the continent was intentionally characterized by its inhabitants. The visual effect created is one that associates Africa exclusively with the color of those who live there, creating a tie between place and race at the same moment it shows the child the extent of the world outside Europe.

Such African imagery was common in the Peter Parley series, and despite often reductive portrayals, Goodrich (and his numerous ghostwriters) were fairly progressive in their views about the continent and its inhabitants. In this image, Parley explains to his child audience that “The black part represents Africa; I have made it black, because the people, who are called Africans, are black, and also very ignorant"; however, in later books, such as Tales About Africa, Parley argues compellingly for an end to slavery. Though his arguments are based mostly on the idea that slavery “exacerbates rather than contains the threat posed by the racialized other,” his generally benign—if ignorant and Eurocentric—views about the continent can be seen in his images (Levander 237). It is perhaps for this reason that the image was kept in the British version of the book. By 1829 the abolition movement had made deep inroads in Britain: the Crown took over the Royal African Company in 1821 in order to more closely monitor its workings and ensure that the ban on slave trading was enforced (Gascoigne 57); in 1834 slavery was officially abolished in the British colonies (Walvin 65). In the United States, however, the American Civil War would not put an end to slavery for another forty-four years.

Collection

Accession Number

CA 17220 no. 952

Bibliography

Butts, Dennis. "How Children's Literature Changed: What Happened in the 1840s?" The Lion and the Unicorn 21.2 (1997): 153-162. Print.

Gascoigne, John. “Empire.” An Oxford Companion to The Romantic Age: British Culture 1776-1832. Gen. Ed. Iain McCalman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. 51-58. Print.

Leininger, Rev. Philip W. “Samuel Goodrich.” The Oxford Companion to American Literature. Ed. James D. Hart. 6th ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 252. Print.

Levander, Caroline Field. " 'Let Her White Progeny Offset Her Dark One': The Child and the Racial Politics of Nation Making." American Literature 76.2 (2004): 221-246. Print.

Walvin, James. “Slavery.” An Oxford Companion to The Romantic Age: British Culture 1776-1832. Gen. Ed. Iain McCalman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. 58-65. Print.