Several years ago I offered a graduate seminar in Romantic period drama, basing my choice of plays on Jeffrey Cox and Michael Gamer’s Broadview Anthology of Romantic Drama, which had recently appeared, as well as Peter Duthie’s edition of Joanna Baillie’s Plays on the Passions.

I wanted to offer a broad range of plays to span the sublime-ridiculous axis within a fairly tight time span. My focus was on the material conditions of playwriting, acting, and even attending theatres during the period, with less attention given to the difficulties of producing a play and of doing so within physically challenging work spaces.

Our mandate for the course was to consider Romantic-period London theatres to be the central cultural institution of the day. I present the genre of drama to my students by explaining that plays, whether written to be performed or to be read as “mental theatre,” were used to work through key issues of the day, and that letters and memoirs of the time often represented thoughts and behavior as if dramatized. Novels frequently contained references to the theatre or specific plays, and occasionally included scenes of amateur playacting in order to make social commentary. Playwrights and poets wanted to stage contemporary issues in visible confrontations, whether of politics (revolution versus maintaining the status quo, Whigs versus Tories, Parliament versus the monarchy); national identity (patriotism versus Jacobinism, British culture versus colonial culture, abolition versus the slave economy); and/or gender relations (feminism versus patriarchy, the marriage market, family structure). We also considered how theatres were managed, the difficulties facing playwrights who had only three main theatres to submit their work to, and how people used the theatre auditorium as a way to stage their own social performance.

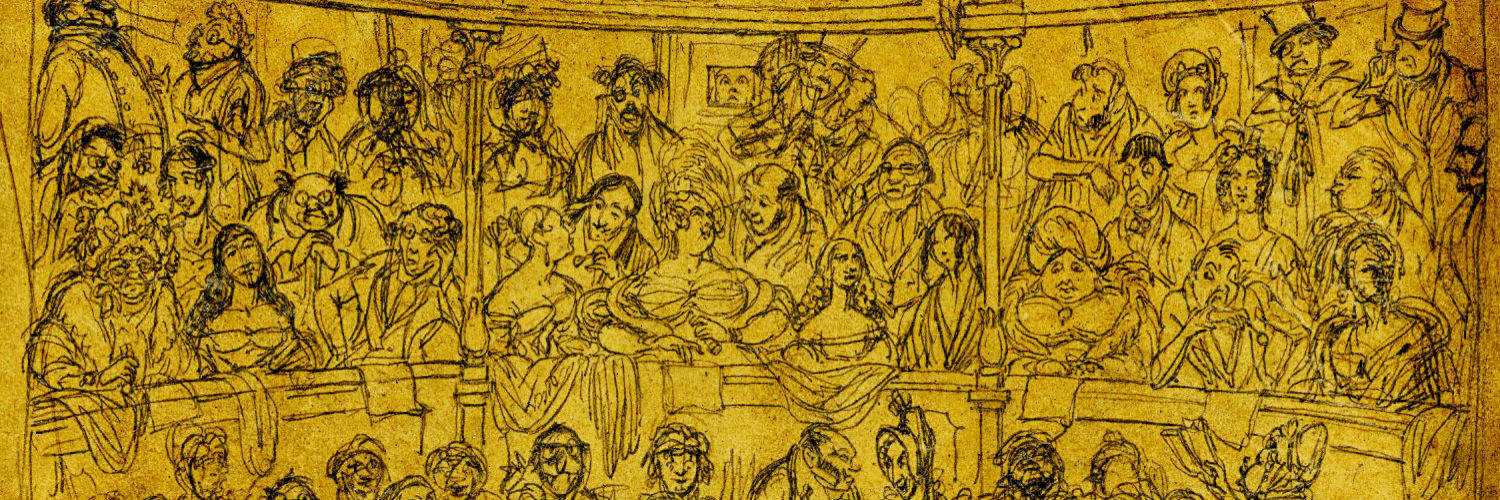

Finally, we attempted to understand an audience experience so different from our own in which, for earlier Romantic plays, performances were held in lighted rather than darkened theatres. Sputtering candlewax, the heat generated by hundreds of candles and spectators, and the constant movement of lighting attendants only added to the confusion created by those audience members more concerned to display themselves or to visit their friends than to watch the actors on stage. Toward the end of the period enlarged theatres meant actors were too distant to hear well while the still brightly lit audience space made the stage hard to see as well. We were forced to reconsider the normative high value given to text-based literature, and to read these plays differently: to read them as staged, to appreciate each genre by its own terms, and to hear the confusion and hubbub that surrounded these plays as part of their cultural value. I wanted us to study representative plays of the period, from tragedies and sentimental comedies to melodrama and closet dramas, while paying attention to dramatic form and representation. Of course, this aspect of our discussions always spiraled into content analysis as students became engaged with characters’ struggles rather than the issues such fictions are meant to embody, but we tried to constantly remind ourselves of the material conditions surrounding dramatic production.

We approached our topic through articles by key scholars in the field and relevant websites, and students were excited by how challenging the theoretical tools were that scholars use to analyze these plays, and yet how much fun people were having creating websites to document the material culture of late eighteenth-century and early nineteenth-century theatres and performances. With this discovery another set of x-y axes began to appear over the framework I had structured for the course of a sublime-ridiculous y-axis cut by a historical x-axis, each intersection providing a key to a cultural moment. We now had a multi-level coordinate system in which the x-y axis of history cut by genre was overlaid with an x-axis of materiality cut by a y-axis of theory. Added to these coordinating vectors was our own axial supplement of difficulty cut by enjoyment. Difficulty was articulated by genre and theory; pleasure by history and materiality. As with any supplement, our own vectors held more truth-value for us. Out of the students’ engagement with supplementary materials, the intersections of difficulty and pleasure began to chart our understanding and reconstruction of Romantic drama and stagecraft. It was not that the sublime and the difficult were synchronized against the ridiculous and pleasure, but rather that both the sublime and ridiculous were modulated by the cultural moment while pleasure showed us when difficulty was valuable and when it only interfered in our historical reconstruction. We learned to read more into the contradiction between the difficulty of a woman learning her craft while knowing the danger to her reputation for traveling to theatres alone at night—or, if her play was being staged, for staying alone with the dramatic company during rehearsals—and the fact that women wrote some of the most hilarious domestic comedies of the late eighteenth century. No longer could breeches parts and gender-bending be taken as anything other than social commentary, but we laughed all the harder at the jokes, mistakes, and misunderstandings that ensued from such masquerades. The axial pairs shifted and adjusted as we went, creating ways to chart our entrée into Romantic theatricality and its peculiar relation to British Romantic culture.

Our range of plays reflected both sets of axial descriptors: we went from the sit-coms of the day, such as Hannah Cowley’s A Bold Stroke for a Husband (1783) and Elizabeth Inchbald’s Every One Has His Fault (1793), to the high tragic art of Joanna Baillie’s Plays on the Passions (1798) and Shelley’s The Cenci (1819); from the orientalism of George Colman the Younger’s Blue-Beard; or, Female Curiosity! (1798) to the absurdity of his burlesque Quadrupeds of Quedlinburgh (1811). Our scholarly framing came from Catherine Burroughs’Women in British Romantic Theatre and Closet Stages, Ellen Donkin’s Getting into the Act: Women Playwrights in London 1776-1829, Daniel Watkins’ Materialist Critique of English Romantic Drama, along with a slew of journal articles.

For instance, we read Peter Thomson’s chapter on “The Early Career of George Colman the Younger” and Greg Kucich’s “‘A Haunted Ruin’: Romantic Drama, Renaissance Tradition, and the Critical Establishment” for George Colman the Younger’s Blue-Beard, and then compared the Gothicism and the treatment of the grotesque in Blue-Beard to that of Manfred, while also considering the implications of closet drama and gender through Burroughs’ Closet Stages.

Students noted that Byron’s use of the supernatural in Manfred bore a striking resemblance to that of Colman’s Blue-Beard, while his medievalism served the same purpose as Colman’s orientalism in defamiliarizing contemporary issues so that they could be resituated and put under pressure. Manfred’s supernaturalism, they felt, revealed an indictment of the critical trappings at Drury Lane, as well as of the blossoming field of theatre review and literary criticism that hobbled Byron’s dramatic freedom. Colman was used to the less restrictive atmosphere of Haymarket Theatre where his father was manager, a position he then took over, and preferred more popular forms to engage critique.

Comparing a closet drama to an afterpiece was instructive, since in both forms questions of gender can be treated more ambiguously than in the hard give-and-take of domestic comedy or the dire consequences of tragedy. Blue-Beard’s melodramatic hippodrama with a gothically bleeding “Blue Chamber” used a different kind of specularity from Byron’s, with live horses instead of ethereal spirits, and a Turkish locale instead of Byron’s alpine sublime. Its fairy tale treatment of women’s subject-status and their right to knowledge provided a greater gender critique than did Manfred’s mysterious soul-mate Astarte whose absent presence haunts the play, yet whose unverifiable life and death settles the focus squarely on Manfred and his hallucinatory world.

Thomas John Dibdin’s pantomime Harlequin and Humpo; or, Columbine by Candlelight! (1812) was our treat for the last day of class, its deliciousness savored by students traumatized by Beatrice’s fate in The Cenci; unable to dismiss their technological sophistication enough to see why Manfred was not stageable; and overwhelmed by this point with densely written scholarship. Yet it was not pure fun, crossed as it was by the very issues raised in the plays we had already read; in hindsight,Harlequin and Humpo provides the real key to our experience of the course. On the one hand, its inclusion in the Broadview anthology and in my syllabus demanded that we take it seriously; on the other hand, as social satire its antics lack the deeper cuts of Voltaire’s satiric plays or even Inchbald’s domestic comedies. But I wanted to take seriously Jeffrey Cox’s questioning of long-held claims that melodrama caused the death of tragedy or foreshadowed modern drama

, and I also wanted to parse pantomime with both forms to find how the melodrama of everyday life rewrote the tragedy of history by allowing theatre-goers to simply have fun.

For my students I wanted to pose the question of how pantomime changes the understanding we had been developing of Romantic performance: was Dibdin’s play a devolution or a critique? Historically, the pantomime was first performed as a Christmas pantomime at Drury Lane, 26 December 1812, the year that saw the Luddite bill in Parliament for capital punishment against framebreakers, and Byron’s maiden speech; the second year of the Regency amid George III’s increasing insanity; and Napoleon’s invasion and then retreat from Moscow. It was a year of chaos and madness, at the same time endowed with the Regency’s characteristic high-spirits and playfulness. Dibdin’s mishmash of genres captures the year’s contradictory aspects and sense of tumult. Its subtitle indicates mystery and revelation, surely also a hint at the unknowns to come regarding Napoleon, worker unrest, abolition and its effect on the sugar trade. Moreover, after the debut just a month later, January 23, 1813, of Coleridge’s tragedy Remorse: A Tragedy, in Five Acts, it was often double-billed with Dibdin’s play as the afterpiece, surely a sign of the despair these unknowns could unfold. That was our first set of axial coordinates: 1812 cut by a harlequinade.

Our second set of axes confronted the materiality of putting on this bizarre performance (and wondering why it could be staged when Manfred could not) cut by Bakhtin’s theory of the carnevalesque, but also theories of how theatre reflected revolution and war, and how women playwrights were losing out to male writers. Although Joanna Baillie’s third volume of plays was also published in 1812, this did not signal success for women dramaturges since her dramas were for the most part read rather than performed. If the pairing of Remorse with Harlequin and Humpo contradicts the theory that serious dramaturgy suffered under the popularity of the ridiculous, the closeting of Baillie’s plays does suggest a silencing of female voices, if not of tragedy itself. Columbine gained new significance in this comparative, and we wondered at the significance of her being closeted by the evil witch Owletta, and her forced marriage to the deformed Humpino. Finally, we were faced with the axes of difficulty and pleasure: a theatrical that is highly historicized, ephemeral, and non-transcendent that nonetheless made us laugh. How it did so became the puzzle to unpack, since understanding that allowed us back into plays we’d read earlier to see if our intellectual enjoyment there could now take on a more sincere pleasure in plays that are likewise historically situated and culturally distant, if closer to our standards of taste and literary norms.

The full title of Dibdin’s play is Sketch of the New Melo-Dramatick Comick Pantomime called Harlequin and Humpo; or, Columbine by Candlelight! The reviews at first trashed it, yet it ran forty-eight nights and was, like Blue-Beard, one of the great successes of its genre. Dibdin had an even freer rein with his pen than Colman since he began his career as an actor and writer for Sadler’s Wells, and also wrote for other secondary theatres before moving to Covent Garden and finally becoming manager of Drury Lane and then Surrey Theatre. If tragedy provides the sublime and Gothic yields the grotesque, pantomime gives us the ridiculous. How might the ridiculous provide the underside of the sublime? How might it reveal the Gothic as pretentious artifice rather than psychological insight? How could we make sense, in other words, of Regency humor? The pantomime’s origins in Italian commedia dell’arte, with its puppet-like character types, improvisational style, and slapstick orientation make it appear childish and rustic rather than sophisticated, but could we read it another way? In preparation for our last seminar meeting I gave the students background material on the commedia dell’arte, its importation into northern Europe and Britain, and the similar stylized use of character in the more recently imported opera. We needed to dig underneath stereotyped characters and set scenes to understand why audiences would have found these familiar formulae pleasurable, and how playwrights might motivate such characters and scenes for social critique. How might interruptive “laugh” devices increase emotional distance in order to make a point as much as to augment audience hilarity? How might absurd plot devices make us rethink our own lives and life trajectories? These together with the play’s unsparing use of mistaken identity and pantomimic features captured some of the saturnalian qualities of earlier British traditions surrounding Christmas, I told my students, when lords and peasants threw protocol to the winds for a few topsy-turvy hours. But the saturnalia was always already social commentary, a chance for the oppressed to turn rage to laughter. The difficulty lay in how to decode the laughter, how to understand the violence underlying Regency tastes in elite and bawdy subjects and acts.

The pantomime always began with a ballet that describes a fairy tale set-piece, followed by a mid-scene centered on a fairy character such as Mother Goose, and ending with the harlequinade. All three sections were accompanied by music or had musical interludes when actors broke out into song, and music was always played during processionals. Music provided one of our biggest material difficulties: although the words are usually, but not always, recorded in scripts, typically there is no notation or indication of how the music would have sounded. Students were better able to imagine the pantomimed scenes from their familiarity with mime artists today, but they had trouble reconstructing the visual effects of this play’s pantomimic elements, as well as the aural effects of its sound technologies. In this case the ridiculous was cut both by history and by materiality; theory came to our historical aid in the guise of Bakhtin’s theory of the carnevalesque, which I had briefly introduced earlier in the semester, and once students made the connection some enlightening self-ridicule took place. We realized we had been reading at once too superficially and too deeply—frustrated at finding no meaning, we couldn’t see the meaning in front of us. Having got this far, we still needed help understanding the material aspects of the harlequinade. Nevertheless, we began to enjoy Harlequin and Columbine’s misadventures, chronicled through the series of improbable plots disastrously entangled, checked, and plied through with difficulties created by plotting maids, parasites and duplicitous characters, child-snatchers, braggarts and simpletons, to say nothing of mistaken identity and other plot interventions. We had to tell ourselves to let go of plot motivation, sequencing logic, and interpretive subtlety, but we also had to learn to look for layers of meaning, connections between the performance sections, and cultural significance.

A peculiar quality of the pantomime is its exploitation of the stage’s visual conventions; this created another hurdle for students trained in the play-as-text, but also opened the door to understanding the material conditions of the performance. Dramatic productions usually submerge the artificiality of stage representation beneath the accepted norms for symbolic space, character stability, disguise, temporal movement, and role portrayal. Audience compliance with these norms generates expectations that playwrights and actors will adhere to certain formal and representational models. Like today’s cartoons, pantomime sets out to subvert these models, conventions and rules at every opportunity, an intention already encoded in its use of scenes as the principle unit rather than acts subdivided by scenes. Cartooning, then, offered us our first ‘theoretical’ intervention in understanding materiality. In our discussion of Harlequin and Humpo students began to point out in particular the metacommentary at work in puns on visuality as the layers of the visual and the staged, of what we see and what we allow ourselves to see, become the interference factor in our understanding of everyday life. It is a factor that the play makes all too visible; it was easy for students to come up with examples of near-equal ridiculousness from our own political stage to the social drama of celebrity lives.

A scene that quickly became central to our discussion was that made by a dumb show during a chase scene set in London’s market streets. Although it is morning, the Clown steals a telescope from the optician’s shop and uses it to view the just risen moon. After several musical pieces accompany more movement on stage, the Clown resumes his play with the telescope at which “the figures disappear and one like the Clown takes their place.” In the next musical piece “Presto. Harlequin from a window waves his sword. The telescope changes to a gun, goes off, shoots the Clown, who shams dead,” but when the gunsmith claims his gun “Harlequin enters, pursued, & leaps through one Eye of the Spectacles at the Opticians. Clown in following leaps through the other and their faces appear (painted) thro’ each eye of the [Spectacles], which fall down like a yoke upon Pantaloon’s neck, which stands in place of a nose to them” (stage directions, Scene XIII).

Presto, like circus clowns the characters are miniaturized and displaced, substituted and reconstituted, and are as fantastical in their abilities and whims as genies and spirits. One student had been reading about late eighteenth-century advances in scientific instruments, providing a clue to the visual fascination with optics, from spectacles and telescopes to gun sights. We talked about how the pantomimed scene made us question what we see that we normally wouldn’t, whether a tiny moon in a telescope lens or even a mirrored image. Another student wondered about the connection between this play and The Travels and Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1859) with its similar parodic effects and fascination with telescope-enhanced adventures. There the political commentary is more overt, allowing us to begin to consider the critique Dibdin’s play might be articulating.

As the spectacle scene demonstrates, space and time in Harlequin and Humpo are more ambiguously related to normal frames of reference than is usual in drama so that scenes can shift in rapid succession from one location to another. In rapid succession we move from a king’s palace to a Dutch clockmaker’s to a country pub to a warehouse to a plumber’s shop to a fairy’s cave all at dizzying speed and often for no real reason except for that of the antic. Late in the play the Clown attempts to steal a hurdygurdy “Shew Box” or peep show after watching a performance by animals and dancers. Just as he is leaving with the shew box, “Harlequin strikes it and it encloses the Clown like a Box” (stage directions, Scene XIV). Sizes, physical properties and space-time dimensions change with the same ease as objects viewed alternately through a telescope and the naked eye. Instrumentation becomes a contemporary form of fairy dust, while subjectivity is ungrounded and put into freefall. Students just coming from The Cenci found the freefall glibly problematic on the one hand, and yet on the other, what one student called “a kind of cardboard version” of Beatrici’s moral freefall. If stage space is arbitrary and artificial, so too might be our legal codes, or worse, our moral codes—for surely we had been hard put to condemn Beatrice if we could not quite condone her. Surely she had blurred our moral vision and made us reconsider what we were witnessing. Surely Harlequin’s antics were more than they appeared.

The fairy tale, we thought from the outset, would provide an apt terrain for political allusions, for social commentary and for plumbing the depths of the popular imaginary. Here was ground for my students to discover that all they had laboriously construed over the semester concerning Romantic drama could be subjected to a severe roasting. They noted in particular its antecedent in 1950s-era “Looney Tunes,” in which indestructible cartoon characters caricature prominent social and political figures. Sir Arthur, “a gallant Knight, afterwards Harlequin,” as the role list explains, provides a stock character of British legend: the knightly King Arthur. Humpo, by contrast, is King of the Dwarfs, denied regal decency by his signifying name and his transformation into the stock zanni Pantaloon (normally spelled Pantalone). He is a literally unenlightened ruler, whose daughter may not see the sun until she is eighteen due to the fairy Owletta’s curse, and the dupe of others. Sir Arthur’s antagonist is the Prince of the Dwarfs, Humpino, to whom the Princess has been promised in marriage; the anticipation of this disastrous wedding begins the rapid-paced action, in which the Princess is magically changed to Columbine and her lover Sir Arthur to Harlequin in order to escape the dire event. One student compared reading the play to seeing only the storyboards for a Hollywood film and then trying to imagine the movie in its finished state without being able to see it. Textually the play requires enormous leaps of the imagination.

Worse yet, Dibdin’s characters kept leaping back and forth between fairy tale and harlequinade, so that we kept falling into childhood memories of Grimm’s Fairy Tales just as we would enter the parodic world of commedia dell’arte. The rapid shifts in genre, discursive traditions, character expectations interfered with our ability to follow a basic plot since most of us did not have the cultural knowledge necessary to interpret each of these traditions as they arose in the play. The convergences, slippages, and disjunctures, I felt, were not too different from those of music videos but my students protested being asked to retro-fit our music industry aesthetic to Dibdin’s taller order of the absurd. Again we returned to cartoon animation, in which the two dimensions of the everyday world and the fairy world are also so interrelated that characters move between them almost seamlessly. We also discussed the relation between puppetry and harlequinades, and how the imaginative demands that each of these folk forms make on the audience are similar. Both the cartoon and puppetry frameworks made more palatable the conversion of the Princess and Sir Arthur into their recognizable forms as Columbine and Harlequin, rendering their story inevitable no matter how many plot turns or leaps between different worlds were required to fulfill it. In our favor was the fact that every play we had read seemed to dwell on the problems of star-crossed lovers, unfulfilled love, illicit love, misguided love. We revisited an earlier discussion of how the Austenian problem of the middle-class heroine in search of a husband saturated the theatrical dynamic as much as that of the domestic novel. Contextualizing our harlequinade in this way helped us orient Dibdin’s world of uncomplicated love, fraught, it is true, with barriers and disruptions but nevertheless secure in the primordial compact between Harlequin and Columbine. The play’s task is to resolve how this pair, who unquestionably belong to each other, ultimately survive the Shakespearean trials that constantly thwart their union. But if the play is about Harlequin and Columbine, why then, one student demanded, is the title character Humpo and not Harlequin’s rival Humpino?

As Cox and Gamer remark in their preface to the play, Humpo King of the Dwarves bears a striking resemblance to Napoleon the usurper. We decided that indeed his diminutive stature would visually invoke Napoleon the man, a blow at French visions of grandeur that we thought would be nearly requisite by 1812, while his name indicates a deformed body and deformity of psyche or soul that represents Napoleon’s megalomania. Humpo, providing the play’s political critique and villain, caricatures Napoleon in a manner recognizable in Coleridge’s Remorse, which we had read. Yet he also recalls Tom Thumb, the subject of a highly popular satire by Henry Fielding that we had not read, but which I summarized for them. Fielding’s diminutive Tom is King Arthur’s giant-killer, an anti-Napoleon.

Here was confusion indeed: Humpo, the greatest of the dwarves, is tiny against the full physical, cultural, and heroic stature of Sir (or King) Arthur, but is he defender of the kingdom, as for Fielding, or a Napoleon? It is Humpo, in his grotesque co-role as Pantaloon, who wrecks havoc for Harlequin and Columbine, chasing them through the various scene sets and finally, in Scene XV, forcibly separating them with the aid of the evil fairy Owletta, who had originally benighted the Princess/Columbine. Harlequin is left alone in the fairy’s cavern to be tormented by the Gothic devices of hooting owls and passing specters. Throwing himself on the ground in his despair, Harlequin “recollects his sword, waves it, strikes the ground & rocks without effect, throws it from him angrily—.” Which is to say Arthur’s legendary talent with stone and sword has failed him here and a stronger magic is needed. The sword instantly turns into a bow and arrow, the weapon that will aid him in defeating Owletta and Humpo, and return him as Sir Arthur to the land of fairy, where he is reunited with his beloved Princess, restored from her alternate identity of Columbine.

At the end of the seminar we were left ruminating about alternative identities, alterity, the psychodynamics of id-ego embodiments, and cultural manifestations of all these imaginative projections. We read the spectacle scene as a commentary on Luddite framebreaking, Humpo as a bizarre Napoleon, and the land of dwarves, witches, and harlequins as our everyday world—but mostly we came away with a sense of an audience reveling in the reduction of political uncertainty to visual play. We could see that in Harlequin and Humpo stock characters and masks achieve cultural critique without the high style of Romantic psychodrama, intensely fleshed out characters, or the ambiguities and questions necessary to the Romantic imagination and culturally invested art.

For us, the difficulty of the piece resides in interpreting its dumb shows, connecting the layers of comic and conventional symbolism to a coherent narrative, and following the central themes through all the interpolations and transformations of the play. Dibdin’s foolery with space and time and the arbitrariness of representation is difficult enough to let us find its philosophical counterpart in Wordsworth’s The Borderers, with its equally challenging disorientation of time and space. If for Dibdin the fateful interventions of good and bad fairies are unrelated to personal merit, in The Borderers the ethical becomes another dimension that ambiguates location and temporality, so that personal integrity has everything to do with epistemological stability. Epistemological stability, of course, is what is supremely missing from Harlequin and Humpo, where not even scientific instrumentation provides reliable information, and where if you thought you knew something about plot and characterization, just wait a minute for it all to be undone. In The Borderers, plot and character appear to unveil each other, yet language continually gets in the way—as it does in The Cenci—of our moral determination, our belief in our capacity to decode, interpret, translate literary art according to a strong moral code. Each of these plays—Wordsworth’s, Shelley’s, Dibdin’s—dramatize how morally chaotic a historical moment can be, how the verbal framing of events can swing our moral compass in dizzying ways. Taking a moment to rethink The Borderers and The Cenci made us recalibrate our initially too-superficial approach to Harlequin yet again.

We began to think that Harlequin and Humpo provides a telling example of the ridiculous as an antidote to the sublime: it seemed to us that perhaps 1812 was a ridiculous year as well as a tragic one, or rather its tragedies turned everything upside-down. The play’s distillation of psycho-social relations into essential units symbolically represented and engaged in semiotic foolery, layered onto cultural biases and traditions but invoking more recent developments such as the Gothic as well, also made it easier to see in retrospect how similar features are at work in literary dramas such as Manfred or Count Basil. This required some distillation, of course, but it was easier to do with Dibdin’s play than it would have been if we had started with the sublimity of Count Basil, unpacking it from this perspective without having gone through the absurdity of Harlequin and Humpo. For my students the harlequinade’s fun struck like a sword through our disciplinary assumptions of literary value, genre expectations and valuations, and the aestheticization of fantasy. It cut through the heavy stone of highly theorized interpretations of such plays as well, giving my students back for a moment their sense of delight in the fantastical world that theatre makes possible. We thought it was perhaps for this reason, indeed, that theatre managers had begun sequencing Remorse with Harlequin and Humpo. Then we had a more post-modern moment, and ended the seminar with the idea that perhaps Dibdin’s spectacle should have come first in the sequence, preparing its audience for the moral challenge of Coleridge’s tragedy, and that for us, its heightening of so many intellectual and cultural cacophonies, disruptions, and sacrileges might more usefully have begun our semester than concluded it.