I cried when I downloaded the first image from the new edition of the Songs in the Blake Archive. (How often can one say that about a work of scholarship?) Like The Baptist or The Mariner, I then wandered the halls of my institution buttonholing unsuspecting colleagues with the URL of a lifetime. Trust me, I said, this is Big: a chance to see the potential of a new medium fulfilled. And how appropriate this seemed for Blake, the artisan-poet for whom the message was always inextricable from the medium. At the Blake Archive they are doing scholarly work for the ages. What follows is an insider's report on that important work from the Archive's Project Manager, Matt Kirschenbaum.

Steve's kind words about our electronic edition of the Songs of Innocence and of Experience, copy Z, started me wondering about the number of hours that had actually gone into making it happen.

But there's no simple way to do the math. Before anyone at the Blake Archive even went near a scanner or a keyboard, the editors first undertook lengthy negotiations with the Library of Congress that culminated in a six-day shoot of its Lessing J. Rosenwald collection (nearly 600 images in all); the 4x5" transparencies thus produced were each then checked against the original Blake material on a calibrated light-box for color fidelity. Next these transparencies had to be scanned: in the case of the Songs, it took 15 or 20 minutes for a project assistant to create a high-resolution (300 dpi), scaled digital image for each of the book's 54 plates. Then Joe Viscomi had to color-correct them all in Photoshop (working with a professional-grade hooded PressView monitor), a painstaking process that can take anywhere from thirty minutes to several hours for each image. Bob Essick's tagging of the bibliographic details of the original work took several hours, at least -- while Morris Eaves and his assistant Kari Kraus's meticulous inventory of every illustration on every plate in order to produce a complete visual concordance of the work took a great many hours more (Essick handles this arduous task for a number of the Archive's other editions). Additional time was spent preparing and proofing the editors' diplomatic transcriptions that accompany the images. Add to all of that the time it then took me to put everything together, assembling and parsing all of the different text and image files to ensure that the complex operations that had gone into creating them had been performed correctly in every instance. And none of the above takes into account the long months of testing and development that had first gone into establishing the basic structure of the Archive, its SGML tag-set, the logic of its search engines, the layout of its interface, and the behavior of its specialized Java enhancements.

What I've just described is the same process that goes into each of the illuminated books that is added to the Archive's collections, though we work with items from a number of institutions besides the Library of Congress and will eventually move beyond the illuminated canon to Blake's paintings, drawings, engravings, manuscripts, and letters. An accounting like the one above goes a long way towards deflating the assumptions of those who think that electronic editing is mainly a matter of automagically zapping books into cyberspace. Electronic editing is work, and I mention this because a project like the Blake Archive is, truth be told, a long way from the desktop cottage industries imagined by early cyber-enthusiasts. Despite its "virtual" home on the World-Wide Web, the Archive requires a real institutional infrastructure, as well as real scholarly labor and expertise, real technical labor and expertise, and, finally, real money (the project is currently funded by the Getty Grant Program, among other sources).

The title of my own position at the Blake Archive is Project Manager; I've had the job since June of 1997, when I took over from Amy Sexton. The Project Manager is really responsible to two sets of people: first, Morris Eaves, Robert Essick, and Joseph Viscomi, the Blake scholars who are the Archive's editors -- each of them based at a separate university -- and second, the staff of the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities (IATH) here at the University of Virginia, where the Archive is housed and where I work. Under such circumstances, communications skills are probably at least as important to my job as the technical knowledge I possess. Much of a typical day for me at the Blake Archive is spent talking to people: the editors via email or the telephone, and other staff members at the Institute in meetings or impromptu conversation. One of our Java applets has suddenly stopped doing what it's supposed to? I stick my head into Rob Bingler's cubicle. Our search engines are sputtering? Time to find out if Dave Cosca's been moving .config files around on the server. Our SGML needs polishing? I catch Dan Pitti, IATH's Project Director, over by the coffee machine and we set up a time to look at the DTD. In the meantime, while all of this is going on, the day's messages from the project's discussion list are accumulating in my email queue: Joe wants another copy of an image he's found a flaw in; could I FTP it to Chapel Hill, please? Morris has discovered an arcane formatting problem in our stylesheets; what can be done about it? Bob, who tags information for our bibliographic headers and illustration descriptions at an astonishing rate, wants to know whether he should send me the latest files he's prepared, or wait until he's done a few more. While I respond to these, other messages come in: What is our convention for line numbering on the plates to be? How can we best present copyright information to a user? Should our tagging be emphasizing the logical structure of Blake's poetry or the physical structure of his books? Well, what does that then mean for the line numbering question? Given that each of the editors is at a separate university, and that none of them are here with me in Virginia, it's crucial that these discussions remain organized and focused and that we separate major editorial or design issues from the mundane business of data management. To that end, I put a great deal of effort into monitoring and directing these virtual conversations, bringing some questions to the forefront for immediate attention while tabling others in what's become known as (of course) our X-Files. All traffic on the project list is also reflected to a log file which, extending back for almost three years, now contains over 2000 messages on matters large and small. John Unsworth, the Institute's Director, is fond of pointing out that this day-by-day record of the development of one of the humanities' earliest electronic editing projects may well prove as valuable in fifty years' time as the images and texts we're producing with current technology and encoding standards.

Although I'm a graduate student in the English Department at Virginia, I'm not a Blake scholar or a Romanticist by training. (My own academic work is on more contemporary subjects: I'm writing a dissertation on hypertext in hypertext, addressing such topics as the cultural poetics of information design and computer modeling.) While my technical knowledge is thus greater than the average humanist's, I have no formal computer science background -- everything I know I've learned on the job, either at the Archive or before that in two years at Alderman Library's Electronic Text Center. What this means for project management is that while I'm not a Java programmer, I still have to know enough about how Java works to be able to hold a conversation with one of the Institute's programmers, communicate the results of that conversation to the editors (who will know even less about Java, but must think through the ramifications of technical matters for their editing of Blake), and then communicate their concerns back to the programmer (who will know his or her Java inside and out, but little about Blake and less about the exigencies of scholarly editing). The Blake Archive also has one part-time project assistant, Greg Murray, a graduate student in the Religious Studies Department here. While I'm visiting with the programmers or typing email back to the editors, Greg's busy scanning transparencies, keeping our image production records, grinding away at the SGML backlog, and proofing finished works on our private testing server.

The public Archive is a complex Web site, and perhaps imposing for the first-time or casual user. But I think we've come to accept that in order to create a resource with lasting scholarly value we have to forego some of the instant point-and-click gratification that seems endemic to the Web. Those users who simply want to view the Archive's images can get to them with relative ease, but to really take full advantage of the site users must be prepared to spend some time with our help documentation and to come to grips with the Archive's specialized tools. The Java applets, for example, are not "bells and whistles" (a noxious phrase, much over-used in my opinion) but rather computational implementations of certain important editorial principles: in the case of Inote, that an image ought to be able to function as an integral part of the Archive's information-base rather than as just a static ornament on the page; or, in the case of the ImageSizer, that part of what "facsimile" editing means is consistently presenting an image at its true size, even on the flickering surface of a computer screen. In like manner, we deliberately design for high-end machines, and for the future, rather than for the hardware and software that is the lowest common denominator of the present. (In other words, the Blake Archive does not have a text-only version -- though users can opt for Java or non-Java presentation.)

The Institute itself is a unique environment in which to work. In addition to the Blake Archive, there are a number of other major humanities computing projects under development here -- Jerry McGann's Rossetti Archive (a sister project of sorts), Ed Ayers's mammoth Valley of the Shadow Civil War database, electronic editing initiatives for both Whitman and Dickinson, architectural historians producing computer-aided models and visualizations, and so on. My only reservation about the Institute's work, really, is a slippery slope from the remarkable to the routine that sometimes makes it easy to lose sight of the depth of an accomplishment. Last August, for example, the Blake Archive finally achieved a breakthrough with The Book of Thel, copy F (our prototype edition), reaching a point where a user could perform a search for (say) "eagle" -- and not just eagles in Blake's written text, but eagles as parts of the illustrations on the plates -- and have the search engine consult the SGML, find the appropriate plate with its accompanying editorial commentary, and then display a color-corrected high-resolution image, zoomed to the particular quadrant of the plate in which the eagle appears, with the option to see the plate resized to its true physical dimensions. Nowadays the novelty of looking at that eagle has pretty much worn off among the folks in the cubicles here -- which means that with the Blake Archive now augmenting its public holdings on a regular basis -- additional copies of Thel, copies of Visions of the Daughters of Albion, Songs of Innocence and of Experience, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Europe, America, The Book of Urizen, and so forth -- the project must begin finding what have been its intended audiences all along: scholarly, artistic, and other communities on the Internet at large.

We also very much hope that the Archive may lure some skeptics onto the Web for the first time. If the Songs don't do that, then the 3D walk-through of Blake's workshop and 1809 exhibition that we've talked about constructing might.

Matthew

Kirschenbaum

Department of English and IATH

University of Virginia

The William Blake Archive is located at http://www.blakearchive.org. For a detailed overview of the project, select the Plan of the Archive from the main index page. To view the Songs and other electronic editions, select Works in the Archive from the main index page.

Over two dozen copies of the combined Songs of Innocence and of Experience are extant today, as well as additional copies of Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience printed separately. The Blake Archive is reproducing exemplary copies of both the combined and the individual Songs from each of their printings in order to permit users to study variations in the plate order, coloring, and other aspects of the physical production of the works. (The Blake Archive will eventually include at least eight copies of the combined Songs and two copies of the Songs of Innocence, as well as related drawings, proofs, and posthumous impressions.) Copy Z of the combined Songs was printed late in Blake's career, c. 1826.

Each image in the Archive is presented as an in-line JPEG at 100 dpi (dots-per-inch) with the option to view a 300 dpi JPEG englargement for the study of details (see below). All images have information about their source and their production histo ry embedded directly in the header of the JPEG image file. The Archive's editors retain the original TIFF source files for these JPEG derivatives on tape.

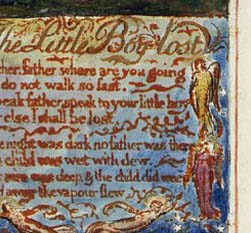

Details (100 dpi and 300 dpi) from the Songs, copy Z, plate 13 ("The Little Boy Lost").

Morris Eaves has recently written on the collaborative aspect of the project in issue 3.2 of the Journal of Electronic Publishing: "Collaboration Takes More Than E-Mail."

SGML, or Standard Generalized Markup Language, is not a programming language. It's a descriptive meta-language used to encode (or tag) all textual data in the Archive. Blake's own poetry and prose, bibliographic information about a wo rk, copy, or plate, and illustration descriptions (see below) are all prepared with SGML encoding, thus ensuring that the data will remain usable even as platforms and file formats change over time.

Here's an example of the SGML we used to describe the shepherd from the Songs, copy Z, plate 5 (lower right quadrant):

<component type="figure" location="D"> <characteristic>shepherd</characteristic> <characteristic>male</characteristic> <characteristic>young</characteristic> <characteristic>short hair</characteristic> <characteristic>tights</characteristic> <characteristic>standing</characteristic> <characteristic>contrapposto</characteristic> <characteristic>looking</characteristic> <illusobjdesc> A young, short-haired male shepherd in tights stands in contrapposto, watching his grazing flock of sheep--perhaps looking at the sheep that lifts its head toward him. He holds a crook in his left hand; his purse is visible near his right knee. </illusobjdesc> </component>Note that the crook and purse would have their own separate entries, as does every other discrete visual component of the plate, as well as the plate as a whole. This itemizing is what enables users to conduct a search across the Archive's material s for all shepherds (or all shepherds with short hair or all shepherds with short hair on the same plate as sheep).

A set of SGML tags designed for a specific purpose is known as a Document Type Definition, or DTD. (HTML is itself an SGML DTD -- hence the stylistic resemblance of the above tags to HTML code.) The Blake Archive uses several speciali zed DTDs developed at IATH to encode its materials.

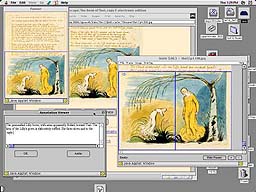

Inote is specialized software developed at IATH, written in Java. It is available for download here. Inote is an image annotation tool: it allows us to attach what are the equivalent of virtual Post-It notes to different parts of an image, with the content of those notes (or annotations) being both browsable by users as well as visible to our search engines. The result is that images become a functional part of the Archive's information-base rather than serving (only) as something to look at. In addition, working with their own copy of Inote on a local machine, users can construct their own personal annotations for the images, creating opportunities both for serious scholarly study and for students in the classroom.

In the screenshot below (The Book of Thel, copy F, plate 4), the main browser window is visible in the background, with the Inote window to the right (showing the two lower quadrants of the image), Inote's panner (simply a navigational aid) reveali ng the full image at top left, and an annotation window displaying editorial commentary at bottom left.

The Archive also uses a second specialized piece of software, also written in Java at IATH, called the ImageSizer. This tool allows users to view images on their own screen at the actual physical dimensions of the original (important for us in part because Blake's works are often imagined to be larger in size than they actually are).

For the most current information about materials recently

published or to be available soon, select the Archive Update from

the Blake Archive's main index page.