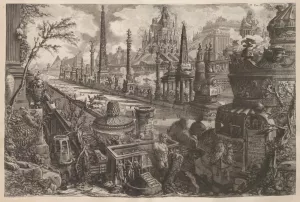

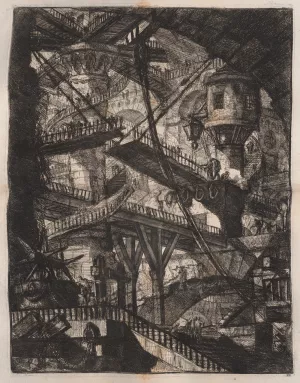

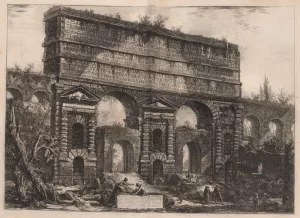

Students and scholars of British Romanticism likely know the work of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (Italian, 1720-1778) through at least one of two lenses: the gaze of the grand tourists or the hallucinations of Thomas De Quincey’s English opium eater. His architectural studies of Rome’s scenic ruins, urban vistas, and archaeological marvels nourished the cultures of antiquarianism and tourism as well as the cults of the ruin and the Romantic artist. His Carceri d’invenzione, or “Imaginary Prisons,” constitutes a key series of critical prints that together suggest parallels between architectural and mental spaces that strain beyond reality, reach beyond received ideas of structure and even gesture, perhaps, to the human imagination itself. Piranesi’s popular vedute, or views, of tourist sites and the Italian architect-artist’s controversial series of prisons make up only a small fraction of his prodigious output. The totality of Piranesi’s productions offer arresting perspectives that collectively map onto a wide range of concerns germane to Romanticism: antiquarianism and archaeology, the critical force of imagination, the relation between genius and invention, the sublime, and the evocative powers and representational limitations of print.

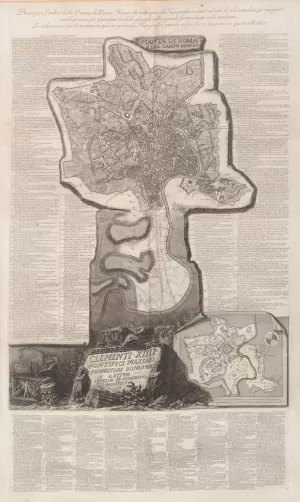

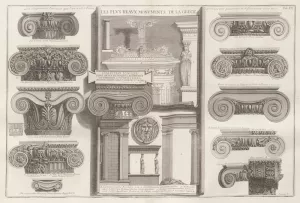

Piranesi’s images often take the form of word-image composites that present a radical form of picturing urban, ancient, and carceral realities alongside a wider representational matrix. Importantly, the inaccessibility of his prints, in addition to divisions between the visual and the verbal in the development of art history have obscured this vital feature of his œuvre. Piranesi’s annotated images and cross-referenced maps come as works of both information and imagination, taking an overtly aestheticized approach to architecture that foregrounds perception as a point of entry for the viewer’s engagement. They merge encyclopedism with art. The material in their captions—sometimes historical and objective, other times speculative and discursive—suggests the ways Piranesi’s works combine material evidence with aesthetic theory to comprehend physical remains through imaginative reconstruction. Across Enlightenment rationality and antiquarian organization, on the one hand, and the creative imagination and visual aesthetics, on the other, Piranesi’s full body of work at once provides striking points of departure as well as significant supplements to the print culture of the Romantic period.

Piranesi’s images have a complex publication and commercial history. Many, and especially his views of Rome, were created to be sold individually but also appeared in bound collections, whether personally assembled or officially published. Hundreds more originally took shape in—and were fundamentally integrated into—books. However, many were subsequently separated from those publications and were sold and studied individually, as art met the market. Roughly sixty years after his death, Piranesi’s complete works were published in a large-scale 29-volume set by Didot press in Paris (1835-9). This edition represents a crucial stage in his reception and afterlife. With the decisive virtue of its comprehensive scope, the frequently ephemeral forms of Piranesi’s work were carried into a new present that now allows unique access to the interconnections his productions invite. And like the original editions of his publications, complete sets of the Didot Press set, especially with all of the images, are rare.

The Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections at the University of South Carolina holds one such set. It is the foundation of a developing project with two components:

1) Digital collection (http://digital.tcl.sc.edu/cdm/search/collection/piranesi) reproducing each volume and an interactive digital project (https://scalar.usc.edu/works/piranesidigitalproject/index). This curatorial work reassembles and illuminates Piranesi’s publications in new ways, and these twinned components represent the challenges of digital reproductions whose relative scales and interactive details warrant attention and benefit from different digital tools. The digital collection maintains the books as books—it represents their visual scales by duplicating the images as they appear in the bound volumes, whether as two-page spreads, large foldouts, or smaller images set two to a page. The digital project, housed on the open-source platform Scalar, allows for different organizing structures and enacts the hypertextual connections that Piranesi’s annotations and cross-references seem to predict. The varied organizational structures that Scalar affords mean that Piranesi’s works can be grouped according to genre or subject matter as well as their publication context; his images can also be used to annotate other images, as the cross-references in some of his maps suggest. Scalar sacrifices, though, issues of scale and page orientation. For an artist who persistently manipulated scale and detail, this dual approach becomes a necessary approximation of Piranesi’s multi-faceted extensions of the print medium.

2) “The Sublime Dreams of Piranesi” exhibition acts as a complement to that digital project, which aims to share nearly all his images and, as of 2025, includes critical essays on each of the Vedute di Roma and the first volume of Le Antichità Romane. This Romantic Circles Gallery contextualizes Piranesi’s images to present the full range of genres and disciplines that the artist engaged by suggesting ways they intersect with authors and tropes of British Romanticism.

Correlative with Piranesi’s productions, for the authors associated with Romanticism who mention his works as an influence, there is a tendency to conflate his various subjects and genres—De Quincey “look[s] over” his antiquarian etchings but responds to (Coleridge’s description of) the prisons; Horace Walpole praises his caprices and prisons in the same breath. Piranesi never used the word “dream” to title even his most fantastical works, which instead fit comfortably in the traditional genre of the capriccio, or architectural fancy. Piranesi probably would have scoffed at this designation for any of his works. And yet, the writers Piranesi inspired frequently referred to his images precisely as dreams. It is the imaginary and impossible unreality in some of his images—not only his Carceri and his capricci but also the evocative compositions and exaggerated scales in his Vedute di Roma—that literary authors found most resonant with their own creative efforts. Through this gallery, viewers are invited, wherever possible, to consider the various affordances and restrictions of different media the through direct engagement with historical print materials and their digital surrogates.

Date Published:

Exhibit Items

Collection Credits

Exhibit Bibliography

Bevilacqua, Mario. “The Rome of Piranesi. Views of the Ancient and Modern City.” The Rome of Piranesi: The Eighteenth-Century City in the Great Vedute, edited by Mario Bevilacqua and Mario Gori Sassoli, trans. Fabio Barry, Rome: Artemide, 2007, pp. 39-60.

Bignamini, Ilaria, and Clare Hornsby. Digging and Dealing in Eighteenth-Century Rome. Yale UP, 2010.

Black, Jeremy. Italy and the Grand Tour. Yale UP, 2003.

Byron, George Gordon, Lord. The Major Works, edited by Jerome McGann. Oxford World’s Classics, 1986.

Carlson, Julia. Romantic Marks and Measures: Wordsworth’s Poetry in Fields of Print . U of Pennsylvania P, 2016.

Campbell, Malcom. “Piranesi and Innovation in Eighteenth-Century Roman Printmaking.” Art in Rome in the Eighteenth Century, edited by Edgar Peters Bowron and Joseph J. Rishel, Merrell, 2000, pp. 561-591.

Dars, Célestine. Images of Deception: The Art of Trompe-L’Œil, Phaidon, 1979.

de Leeuw, Ronald. “Dealer and Cicerone: Piranesi and the Grand Tour.” Piranesi as Designer, edited by Sarah E. Lawrence, Cooper-Hewitt, 2007, pp. 241-267.

De Quincey, Thomas. Confessions of an English Opium Eater, edited by Thomas Morrisson, Oxford World’s Classics, 2013.

Dixon, Susan. “The Sources and Fortunes of Piranesi’s Archaeological Illustrations.” Art History, vol. 25, no. 4, 2002, pp. 469-487.

____. “Piranesi and Francesco Bianchini: Capricci in the Service of Pre-scientific Archaeology.” Art History, vol. 22, no. 2, 1999, pp. 184-213.

Ferri, Sabrina. Ruins Past: Modernity in Italy 1744-1836. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2015.

González-Palacios, Alvar. "Piranesi and Furnishings." Piranesi as Designer, edited by Sarah E. Lawrence, Cooper-Hewitt, 2007, pp. 221-239.

Graves, Michael. "Drawing from Piranesi." Piranesi as Designer, edited by Sarah E. Lawrence, Cooper-Hewitt, 2007, pp. 93-121.

Heringman, Noah. Sciences of Antiquity: Romantic Antiquarianism, Natural History, and Knowledge Work. Oxford: 2013.

Huyssen, Andreas. “Nostalgia for Ruins.” Grey Room, no. 23, 2006, pp. 6-21.

Jarrard, Alice. “Perspectives on Piranesi and Theater.” Piranesi as Designer, edited by Sarah E. Lawrence, Cooper-Hewitt, 2007, pp. 201-19.

Kantor-Kazovsky, Lola. Piranesi as Interpreter of Roman Architecture and the Origins of His Intellectual World. Florence, Italy: Leo S. Olschki Editore, 2006.

Keats, John. Poetical Works of John Keats, edited by William Thomas Arnold, Kegan Paul, Trench, and Co., 1884.

Lawrence, Sarah E. “Piranesi’s Aesthetic of Eclecticism.” Piranesi as Designer, edited by Sarah E. Lawrence, Cooper-Hewitt, 2007, pp. 93-121.

Lolla, Maria Grazia. “Ceci n’est pas un monument: Vetusta Monumenta and Antiquarian Aesthetics.” Producing the Past: Aspects of Antiquarian Culture and Practice, 1700-1850, edited by Martin Myrone and Lucy Peltz, Ashgate, 1999, pp. 15-34.

Marshall, David R. “Piranesi’s Creative Imagination: The Capriccio and the Carceri.” The Piranesi Effect, edited by Kerrianne Stone and Gerard Vaughan, Sydney: NewSouth Publishing, 2015, pp. 111-134.

Mayor, A. Hyatt. Giovanni Battista Piranesi. New York: H. Bittner and Co, 1952.

Miller, J. Hillis. The Disappearance of God: Five Nineteenth-Century Writers. Harvard UP, 1963.

Minor, Heather Hyde. Piranesi’s Lost Words. The Pennsylvania State UP, 2015.

Momigliano, Arnaldo. “Ancient History and the Antiquarian.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol. 13, no. 3/4, 1950, pp. 285-315.

Nevola, Francesco. Giovanni Battista Piranesi: The Grotteschi, the Early Years 1720-1750. Rome: Ugo Bozzi, 2009.

Nyberg, Dorothea, and H. Mitchell, editors, Piranesi, Drawings and Etchings at Columbia University: An Exhibition at Low Memorial Library. New York: Avery Architectural Library, 1972.

Pinto, John. Speaking Ruins: Piranesi, Architects and Antiquity in Eighteenth-Century Rome. U of Michigan P, 2012.

Pinto, John and William MacDonald. Hadrian’s Villa and Its Legacy. Yale UP, 1995.

Piranesi, Giovanni Battista. Giovanni Battista Piranesi: Matrici incise 1743-53. Volume 1. Edited by Ginevra Mariani. Milan: Mazzotta, 2010.

____. Giovanni Battista Piranesi: Matrici incise 1756-57. Volume 2. Edited by Ginevra Mariani. Milan: Mazzotta, 2014.

____. Giovanni Battista Piranesi: Matrici incise 1761-65. Volume 3. Edited by Ginevra Mariani. Milan: Mazzotta, 2017.

____. Opere. Paris: Didot, 1835-9. 29 vols.

Roncato, Sergio. “Piranesi and the Infinite Prisons.” Spatial Vision, vol. 21, no. 1-2, 2007, pp. 3-18.

Rosenfeld, Myra Nan. “Picturesque to Sublime: Piranesi’s Stylistic and Technical Development from 1740 to 1761.” The Serpent and the Stylus: Essays on G. B. Piranesi, edited by Mario Bevilacqua, Heather Hyde Minor, and Fabio Barry. The U of Michigan P, 2006, pp. 55-91.

Scott, Jonathan. Piranesi. St. Martin’s P, 1975.

Stafford, Barbara Maria. Body Criticism: Imaging the Unseen in Enlightenment Art and Medicine. MIT P, 1991.

Stewart, Susan. The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture. U of Chicago P, 2020.

Tafuri, Manfredo. The Sphere and the Labyrinth: Avant-gardes and Architecture from Piranesi to the 1970s. MIT P, 1990.

Verschaffel, Bart. “Rome Pictured as a World: On the Function and Meaning of the Staffage in Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s Vedute.” Aspects of Piranesi: Essays on History, Criticism and Invention, edited Dirk De Meyer, Bart Verschaffel, and Pieter-Jan Cierkens, A&S Books, 2015, pp. 118-41.

Walpole, Horace. Anecdotes of Painting, 4th ed., 4 vols., London, 1786.

Wendorf, Richard. “Piranesi's Double Ruin.” Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 34, no. 2, 2001, pp. 161-80.

Wilde, Oscar. Critical Writings of Oscar Wilde, edited by Richard Ellman, U of Chicago P, 1982.

Wilton-Ely, John. The Mind and Art of Giovanni Piranesi. Thames and Hudson, 1978.

____. Giovanni Battista Piranesi: The Complete Etchings. 2 vols. San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Art, 1994.

____. “Design through Fantasy: Piranesi as Designer.” Piranesi as Designer, edited by Sarah E. Lawrence, Cooper-Hewitt, 2007, pp. 11-91. (2007a)

____. “Piranesi and the World of the British Grand Tour.” The Rome of Piranesi: The Eighteenth-Century City in the Great Vedute, edited by Mario Bevilacqua and Mario Gori Sassoli, trans. Fabio Barry, Rome: Artemide, 2007, pp. 67-78. (2007b)

Yerkes, Carolyn, and Heather Hyde Minor. Piranesi Unbound. Princeton UP, 2020.

Yourcenar, Marguerite. The Dark Brain of Piranesi and Other Essays, translated by Richard Howard. Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1984.

Zarucchi, Jeanne Morgan. “The Literary Tradition of Ruins of Rome and a New Consideration of Piranesi’s Staffage Figures.” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 35, no. 3, 2012, 359-380.

Zucker, Paul. “Ruins: An Aesthetic Hybrid.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol 20, no. 2, 1961, 119-130.