Creation Date

5 November 1759

Height

32 cm

Width

38 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

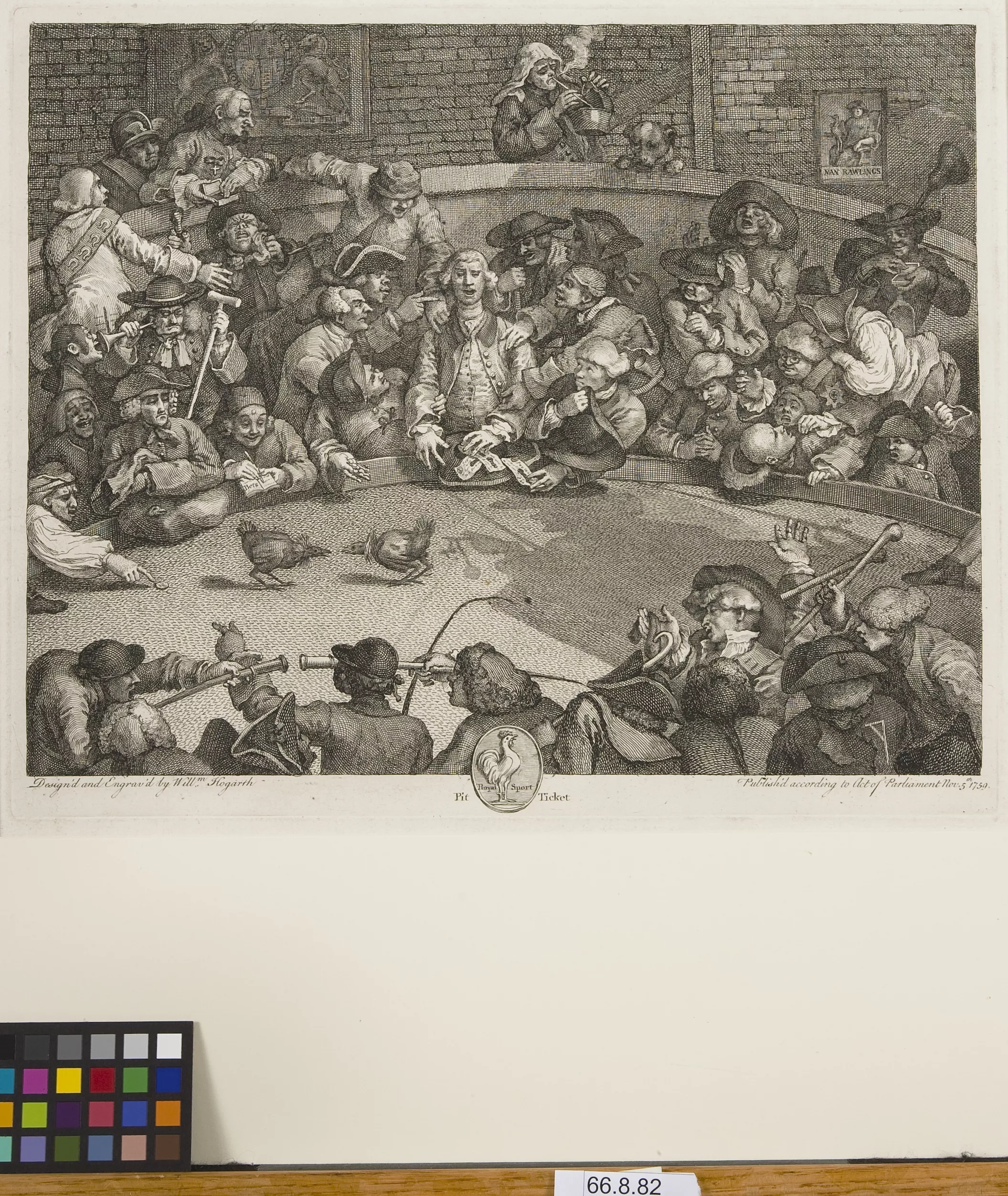

This image depicts a cockfight, with special emphasis on the diversity of spectators in attendance and their singularity of purpose (gambling).

Two cocks are fighting on the left side of the cockpit; one foot of each feeder is visible at opposite ends of the fighting table, (usually constructed as a large table enclosed by a raised rim of about four inches). A shadow, apparently cast by a man suspended overhead in a basket, falls on the table. He has been "exalted" in the basket because he has defaulted on his debts; penniless, he bets his watch and seals on the match.

Blind Lord Albemarle Bertie presides over the betting at the center of the crowd, one hand covering his hat filled with notes. He is surrounded by a couple of butchers, a thief, a farmer, and a post boy. The group on the right contains a nobleman, a carpenter, a Quaker, and a highway man, with a chimney sweep looking on. The group on the left includes a man talking into the trumpet of a lame, deaf man; a neatly dressed man with a cock in a bag; and a man in a skull cap taking notes. A farrier stands above them with his back to the match; he looks at a man wearing a helmet reminiscent of Mercury’s and a French gentleman wearing the cross of St. Louis, both of whom stand behind the barrier. In the near center, also behind the barrier, a man smokes a long pipe next to a mastiff, who watches the match intently. Another crowd stands along the bottom of the cockpit: the hunchback and jockey, Jackson; another jockey; two men spying on each other through telescopes; a couple of drunkards; a man ruefully contemplating his empty purse; and a hangman marked by a chalk gallows on the back of his coat.

The royal arms hang on the brick wall at the back left of the image, inscribed with a broadside depicting Nan Rawlings seated in an arm-chair and holding a fighting cock in her lap. An oval medallion hangs in the center foreground of the image, inscribed with a cock crowing and the phrase “Royal Sport." This medallion is named “Pit Ticket,” a word written on either side of it, and represents a token of admission to the cockfight.

Much of Hogarth’s work was “calculated to display the follies of mankind”: he sought to edify the viewer by depicting men and women failing to make proper moral choices (Clerk 134). He targeted as subjects and audience persons from every level of society, from the aristocracy and middle class who viewed his paintings at the Royal Academy to the lower class and penniless who saw his engravings displayed in the windows of print shops. This range in subject and viewer is found in The Cockpit, which depicts aristocrats (such as Lord Albemarle Bertie), commoners (like the hangman), and foreigners (such as the Frenchman). In a burlesque of Da Vinci’s The Last Supper, Lord Albemarle Bertie is at the center of both the match and the image, presiding over the cockfight in comic imitation of Christ distributing the bread and wine (Stevens 59). Through this visual allusion, Hogarth is able to critique the morality of the cockfight as well as the social mores of those involved. Specifically, the portrayal of the match as presided over by a leading aristocrat suggests a critique of the role and involvement of the upper classes in promoting cruel and debauched behavior. Furthermore, the medallion in the foreground of the image—representative of the tickets granting admission to the Royal Cockpit, and implicitly granting visual access to the viewer—implicates the king as royal patron of the sport and arena. Consequently, the cockfight, especially in this depiction, uses gambling as a common factor to collapse the social hierarchy.

Interestingly, many commentators condemned cockfighting by finding evidence of its corrupting influence in the faces of its spectators. James Boswell writes: “I looked round to see if any of the spectators pitied [the cocks] when mangled and torn in a most cruel manner, but I could not observe the smallest relenting sign in any countenance” (qtd. in Stevens: 59). In attendance at a cockfight, Boswell examines the spectators rather than the spectacle; similarly, The Cockpit portrays a crowd of errant spectators who, because their countenances do not register "the smallest relenting sign," are implied to possess errant morals. The cruelty of the sport is registered not so much in the fighting of the cocks as in the spectators' paradoxical combination of intense, financial investment in the match and careless regard for the actual event: most of the men are so engrossed in making their bets and securing their wagers that they barely watch the fight.

Ironically, Lord Albemarle Bertie, who presides over the match and collects the betting slips, is blind. This element of blind spectatorship is further manifested in the persons of the two men along the bottom of the cockpit who stare at each other through telescopes, thus negating, even erasing, their purposes of aiding and enhancing vision. Through these blinded men, Hogarth gives literal form to the concept of “blind fortune," and “alert[s] his viewers to the natural connection between blind fortune and social chaos, the loss of common bonds of human sympathy and all sense of appropriate social hierarchy” (Craske 48). With these figures of impaired vision—combined with the implication of impaired hearing in the image of the man and listening trumpet—the "fortune" of the cockpit takes on the dual connotations of unreliable chance and risky economy. Consequently, Hogarth seeks to admonish the viewer through a revelation of the cruelty, immorality, and senselessness of cockfighting as figuratively and literally rendered in the corruption of its spectators.

Locations Description

Brought to Britain by the Romans, cockfighting is considered the oldest sporting event in England. Cockfighting was first associated with royalty when Henry VIII had a cockpit built in the palace of Whitehall. James I officially recognized cockfighting as a national sport, even appointing a royal Cockmaster to oversee the fighting-cocks that would appear in the Royal Cockpit (Scott 102). It was particularly encouraged during the reign of Charles II. Located on Birdcage Walk, near St. James Park, at the intersection of Dartmouth and Queen streets, the Royal Cockpit was attached to and associated with the royal palace. When the building was torn down in 1816, the Royal Cockpit moved to Tufton Street, Westminster and operated there until 1828. At the height of its popularity in the eighteenth century, cockfighting attracted greater attention than racing (Scott 110). However, due to moral concerns regarding gambling, cockfighting was prohibited by an act of Parliament in 1849 (5&6 Wm IV cap. 59).

Accession Number

66.8.82

Additional Information

Bibliography

Bindman, David. Hogarth and his Times: Serious Comedy. Berkeley: U of California P, 1997. Print.

Clerk, Thomas and William Hogarth. The Works of William Hogarth: (including the ‘Analysis of Beauty,’) Elucidated by Descriptions, Critical, Moral, and Historical; (founded on the Most Approved Authorities.) To which is Prefixed Some Account of His Life. Edinburgh, 1812. Print.

“Cockfighting.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 03 Jul. 2013.

Craske, Matthew. William Hogarth. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2000. Print.

Dundes, Alan. The Cockfight: A Casebook. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1994. Print.

George, M. Dorothy. Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires Preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum. 11 vols. London: British Museum Publications Limited, 1978. Print.

Hallett, Mark, and Christine Riding, eds. Hogarth. London: Tate, 2006. Print.

Hogarth, William, John Ireland, and John Nichols. Hogarth’s Works with Life and Anecdotal Descriptions of His Pictures. 3 vols. London, 1883. Print.

Pyne, W.H. and William Combe. The Microcosm of London; or, London in Miniature. 3 vols. London: Ackermann, 1904. Print.

Scott, George Ryley. The History of Cockfighting. London: Charles Skilton, 1957. Print.

Stevens, Andrew. Hogarth and the Shows of London. Madison: Elvehjem Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1996. Print.

“Room 8: Crime and Punishment.” Hogarth. Tate Britain: Exhibition. 7 Feb. – 29 April 2007. Tate. Web. 3 July 2013.

Wheatley, Henry B. Hogarth’s London: Pictures of the Manners of the Eighteenth Century. London: Constable, 1909. Print.