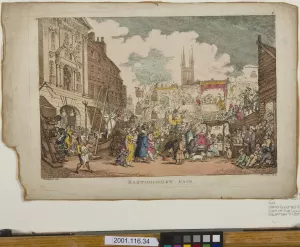

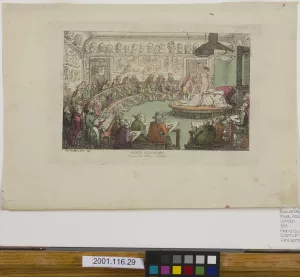

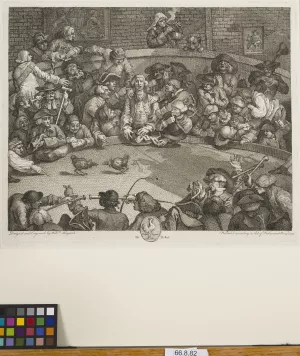

Romantic London is a city of spectacles: from Bartholomew Fair to Covent Garden, from the Great Exhibition Hall to the Royal Academy. These spectacles serve as both the location and occasion for a wide range of viewing practices and interactions, as spectators turn their gaze from the stage and exhibit to the boxes and crowds. This gallery seeks to examine the notions of the viewer and the gaze through the crowd scenes afforded by London’s social calendar of cultural spectacles. Focusing on the formation of the art spectator, this gallery traces the various modes of viewing art—from its conception in life-drawing classes to its display at the Royal Academy Exhibition, and finally to its place in the private collection. The expansion of the viewing public also occurred in sites of drama or live event: from the theatre and Westminster Abbey, which became a tourist site in the eighteenth century, to Bartholomew Fair and the Royal Cockpit, which drew spectators from all classes of society. This circulation of art and the growing public of spectators raises the debate regarding the codification of viewing practices during the Romantic period. As "viewing" became a cultural and social practice available to a wider audience, there was a concerted effort to educate and refine public taste through exhibition catalogues, popular writings, and, as this gallery seeks to demonstrate, through images themselves. Peter de Bolla argues that paintings came to play a role in the education of the eye by “didactically presenting an encyclopedia of looks” (see The Education of the Eye, 62). The gallery further argues that those spectacle scenes which feature the Rückenfigur—the figure who presents his back to the audience—afford the viewer the opportunity to step into the work and actively engage in a range of viewing practices. Rather then excluding the audience, the Rückenfigur draws attention to the spectacle of viewing art and acts as a stand-in for the external viewer; furthermore, the unspecified direction of his gaze allows for a degree of freedom and subversion. Finally, though there are exemplary instances of what Michael Fried terms the state of absorption, or a state of the intense—presumably educated and proper—study of art, the spectacle scene does offer an encyclopedia of looks that abounds in errant spectatorship, ultimately transforming spectators into spectacle (see Fried's Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot). Consequently, this gallery offers images that actively participate in the debate concerning the role of the spectator.