Creation Date

1845

Height

15 cm

Width

23 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

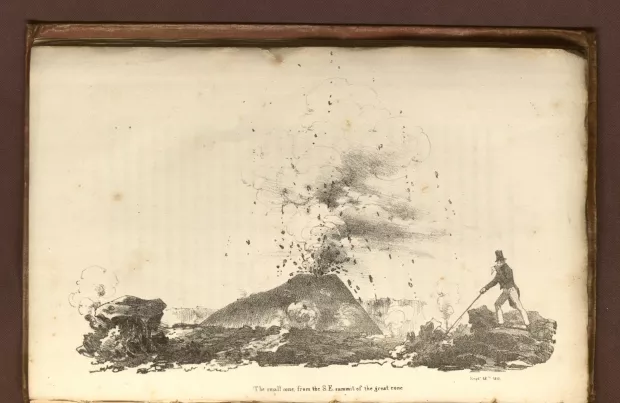

This depiction of Mount Vesuvius represents Romantic culture’s new, more scientific approach to volcanoes, which began to be seen as an attraction for volcanologists and tourists alike. As demonstrated by the human figure—who appears to be performing a hands-on investigation of sputtering lava—the image shows that one can successfully study volcanoes in action. Before this image, Romantic culture was primarily concerned with the volcanoe as an emblem of death and destruction. However, as this engraving suggests, a curiosity grounded in science and notions of the picturesque began to emerge regarding volcanoes and their eruptions.

John Auldjo, the artist himself, stands on the far right of the image, poking the lava with a cane and holding a cloth over his mouth. In the background, the eruption of Vesuvius’ small cone, Monte Somma, blasts small bits of lava into the air; these fragments land near Auldjo. Palo, the highest point of Mount Vesuvius, is not shown in the image. An extensive jumble of what appear to be lava flows, hardened sediment, and rocks take up the foreground of the image.

Because Auldjo does not appear fearful of his surroundings and because the volcanoe does not loom menacingly overhead (it is instead ensconced at a slight distance and, consequently, miniaturized), Mount Vesuvius does not here represent the sublime. Instead, the drawing serves to depict a scientific phenomenon that is beginning to be understood. By depicting both the artist himself and the object of his interest, Mount Vesuvius, this image demonstrates the increasing, active curiosity of Romantic culture in the empirical attributes of volcanoes.

This depiction of Mount Vesuvius represents Romantic culture’s new, more scientific approach to volcanoes, which began to be seen as an attraction for volcanologists and tourists alike. As demonstrated by the human figure—who appears to be performing a hands-on investigation of sputtering lava—the image shows that one can successfully study volcanoes in action. Before this image, Romantic culture was primarily concerned with the volcanoe as an emblem of death and destruction. However, as this engraving suggests, a curiosity grounded in science and notions of the picturesque began to emerge regarding volcanoes and their eruptions.

John Auldjo’s intended that his sketch both educate and inspire his audience; in the accompanying text, Auldjo says that he wants to “excite travelers” (A3). Auldjo hoped his audience would be so captivated by his detailed portrayal of the rocky volcanoe and its rivers of lava that they would venture to see Mount Vesuvius themselves. In this sense, the image functions as an advertisement. Auldjo’s use of a detailed and, as he describes it, panoramic view of Monte Somma allows his viewers to experience more features of the eruption, thus further educating and exciting them.

"The Small Cone" in Sketches of Vesuvius was created in 1831 shortly after a minor eruption by Vesuvius’ small cone, Monte Somma, which is depicted in the sketch. This copy of the image and book was privately owned by Chester H. Thordarson before arriving in Special Collections at the University of Wisconsin—Madison.

Locations Description

Mount Vesuvius

Classified as a Stratovolcano (one with a tall, multi-layered cone), Mount Vesuvius rises to 4,203 feet (1,281 meters). Within the recent centuries, Vesuvius’ height has decreased due to massive eruptions which have destroyed the volcano’s walls. The volcano is located in the Province of Naples near Pompeii, the city destroyed by its eruption in 79 AD. Today Mount Vesuvius has two craters which emit magma. The larger cone is known locally as Palo. The second, newer cone—formed by massive amounts of magma hardening under pressure—is known as Monte Somma. After the 79 A.D. eruption Mount Vesuvius has erupted about twice every century, with no eruptions occurring after 1944 (S. Bisel Secrets of Vesuvius 2-64).

Mont Blanc

Meaning “white mountain” in French, this snow-topped mountain rises to 15,781 feet (4,810 meters) in northeastern Italy and southeastern France, forming the border between the two countries. The eleventh tallest mountain in the world, Mont Blanc was climbed first by the Italians Jacque Balmat and Michel Paccard in 1786; since then, many have climbed the summit, including John Auldjo in 1827 and Theodore Roosevelt in 1886 (R. Irving, Ten Great Mountains 115-117).

Poggiomarino

This commune, located about twenty-five kilometers east of Naples, suffered damage when the lava flow from Mount Vesuvius’ 1834 eruption burned much of its architecture (S. Bisel Secrets of Vesuvius 22).

Copyright

Copyright 2009, Department of Special Collections, Memorial Library, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI

Collection

Accession Number

Thordarson T174

Additional Information

Bisel, Sara Louise Clark. Secrets of Vesuvius. New York, NY: Scholastic Inc., 1990.

Flower, S. J. “Auldjo, John (1805–1886).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. 2 Apr. 2009 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/37135.

Irving, Robert Lock Graham. Ten Great Mountains. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Limited, 1940.

Mayer, Ralph. HarperCollins Dictionary of Art Terms and Techniques. New York, N.Y: HarperPerennial, 1991.

Ridley, Jasper. The Freemasons A History of the World's Most Powerful Secret Society. Grand Rapids: Arcade Publishers, 2002.

Sichel, Walter Sydney. Memoirs of Emma. New York: P. F. Collier & Son, 1910.

Transactions of the Geological Society of London. Geological Society: London, 1856.