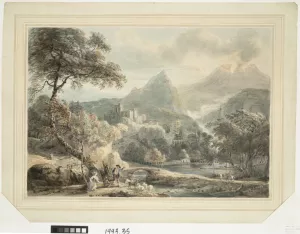

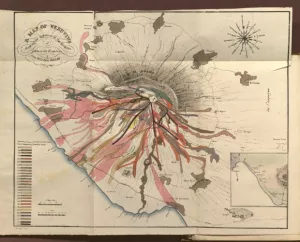

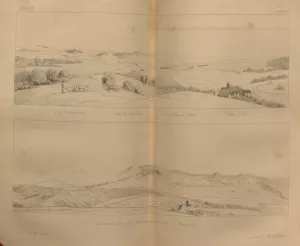

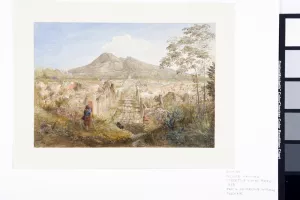

In 1787 Emma Hart (soon to be Lady Emma Hamilton) wrote home to England: “We was last night up Vesuv[i]us at twelve a clock, and in my life I never saw so fine a sight. . . . We saw the lava surround the poor hermit’s house, and take possession of the chapel, notwithstanding it was covered with pictures of Saints and other religious preservatives against the fury of nature. For me, I was enraptured.”[1] Mount Vesuvius, just outside the royal capital of Naples, erupted “with obliging frequency” in the late eighteenth century (as Roy Porter memorably put it).[2] Vesuvius loomed over Europe, inspiring research in natural history and antiquities, a whole genre of painting and other new techniques of illustration, a rich allegorical language for political upheaval, and a booming tourist trade. Emma Hart’s enraptured account reveals her as a new kind of stakeholder in both the pioneering volcanology and the Grand Tourism associated with her soon-to-be-husband, Sir William Hamilton, the “Volcano Lover” (as Susan Sontag called him).[3] It also reveals the tourism, science, and art of this region as a political arena, in which northern European intellectuals and artists appropriated conventions of fieldwork and visual representation from a thriving Neapolitan intelligentsia and used these discourses to expose what they saw as the superstitions of a feudal Catholic regime. Often drawing on Hamilton’s research, other investigators such as Nicolas Desmarest in France, Rudolf Erich Raspe in Germany, and John Whitehurst in England discovered evidence of extinct volcanoes that confirmed the global significance of Vesuvius and its larger neighbor, Mount Etna. Whitehurst never left England, but the painter Joseph Wright of Derby, Whitehurst’s friend and one of the most influential northern European exponents of the volcanic veduta (“view”), painted a portrait of Whitehurst that shows an erupting volcano through the window of the naturalist’s study. Farther afield, naturalists on the voyages of Cook, Bougainville, and other Pacific explorers established that Tahiti, Hawai’i, and scores of other islands were of volcanic origin. The prominence of Vesuvius in this exhibit (4 of 9 images) reflects the large body of visual material available, but it is important to remember that another volcano, Mount Tambora on Sumbawa, Indonesia, created just as profound an impact on European Romanticism when it erupted in 1815, causing the famous “year without a summer” (1816) through the sheer volume of ash that it ejected into the atmosphere. [NH]