Jane Austen was an early entrant to the World Wide Web. One of the best-known and most-visited of all author-based fan sites, The Republic of Pemberley, began its online life back in 1996, at a period when “just 20 million American adults had access to the Internet, about as many as subscribe to satellite radio today” (Manjoo).

The website offers a brief account of its early history, informing us that it began as “a one-horse web bulletin board (message board)” (The Republic of Pemberley). Needless to say, Austen’s web presence—as measured by the hundreds of websites that are devoted to her, both fan-based and academic in orientation—has grown exponentially in the past two decades: a search for “Jane Austen” on Google records 25,800,000 hits.

The teaching opportunities presented by this mass of web publications are practically inexhaustible; in this short essay, however, I will focus on the open-access, scholarly-edited resource released in 2010 that digitally remediates all extant manuscripts of her fiction, Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts.

Of vastly superior quality and far greater accessibility than print facsimiles of her manuscripts, these digitized texts provide students (and scholars) with unprecedented access to high-quality digital surrogates and transcriptions of Austen’s fiction manuscripts.

Use of this resource can be profitably integrated in upper-division undergraduate and graduate courses. In this essay, I want to consider how Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts can be used to explore the following three topics:

- Austen’s material practices of writing and sharing her fiction, and the different audiences she anticipated for her writing in script and print.

- Austen’s development as a writer through comparison and analysis of her fiction manuscripts, which represent her writing at every stage of her career (from 1787, when she was twelve, to 1817, the year of her death).

- The nature of literary archives: what survives and in what form, and the benefits and drawbacks of digitization, with consideration of interface design and screen reading.

In the following essay, I will touch upon each of these topics, providing specific examples of ways in which I have used the material in past courses, as well as offering student feedback and suggestions for future use. I should add that most of these strategies have been used in semester-long, upper-division courses devoted to Austen, as well more recently in a course that was structured around the analysis of various Romantic period manuscripts (using additional digital resources),

but I see no reason why some of these discussions couldn’t be brought into a course with a broader focus.

For example, the inclusion of Austen’s manuscript texts in at least two major anthologies can provide a bridge into introducing the digital surrogates—even in undergraduate surveys—thereby allowing students to begin to take stock of the variety of ways (besides print) that literary texts circulated in the eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century.

The material practices of manuscript culture

Most undergraduate students of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century literature are afforded little—if any—access to manuscripts from the period. The reasons for this are obvious: manuscripts are rare, unique documents and are almost always held by special or private collections, most of which are not available for viewing by undergraduate students. Until very recently, the only way of reproducing manuscripts for those unable to access them in person was via microform or print facsimiles; assigning an undergraduate class text on microform, for which usually only one copy exists and which must be viewed in the library, presents obvious difficulties, while print facsimiles (the way Austen’s manuscripts have historically been reproduced) are generally too expensive to include on a student reading list, or are out of print.

However, many of our period’s canonical texts were unprinted during the author’s lifetime: Wordsworth’s The Prelude; Dorothy Wordsworth’s Journals; Shelley’s “The Masque of Anarchy”; Keats’ poems to Fanny Brawne; and Byron’s “Dedication” to Don Juan, to name just a few. Other works, like Coleridge’s Christabel, circulated for nearly two decades (from 1798 until 1816) in manuscript. But when students encounter theses texts in anthologies, the text’s publication status is usually obscured, and is thus rarely noticed by—or explained to—them.

Moreover, most manuscript texts that students are introduced to—and this is certainly true of Austen’s—have been subjected to the normalizing processes of print, in which spelling has been regularized, evidence of revision has been removed, abbreviations expanded, and so on.

With the release of new digital manuscript archives, the ability to teach students about the material and social practices of manuscript culture, which continued to operate alongside of print, are now emerging. Indeed, high-resolution digital photography, combined with the storage capacity and ease of transmission enabled by the internet, finally seems to have overcome many of the long-standing difficulties involved in the reproduction of high-quality facsimiles of handwritten documents. Current generation digital photography eclipses anything possible in the bi-tonal worlds of lithography and photography, the main technologies for reproducing handwritten documents during the last century and a half. With Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts we are presented with a resource that was unthinkable even a few years ago: digital surrogates of all the extant fiction manuscripts, which amounts to 1,100 pages of fiction written in Austen’s own hand.

A study of Austen’s manuscripts offers occasion for instruction in the period’s material literary culture. Students encountering a digital surrogate of a manuscript such as Austen’s History of England will likely be confronted with a series of new challenges and questions, ones that do not arise when they read the novels—or even the juvenilia—as reproduced in print editions. Unlike most print books, legibility can be an issue with manuscripts. Although the History of England is a fair copy, students may have trouble, at least initially, deciphering Austen’s script. In addition, students can learn about the potential difficulties of attribution and dating in manuscripts (issues that arise far less frequently in print). Nothing in the manuscript of The History of England, for example, plainly indicates that the handwriting and authorship are Austen’s, nor that the watercolor portraits were made by Cassandra Austen. The date of “Saturday Nov. 26th 1791” is presented only on the final page, an unusual placement for those familiar with bibliographical codes derived from modern print. Students will need to learn about how provenance establishes Austen’s authorship and handwriting, and Cassandra’s contributions, and they will also need to be instructed in how questions of dating persist with other fiction manuscripts (such as Lady Susan and The Watsons).

One of the ways I begin to engage students with the surviving manuscripts is to have them peruse the index of Austen’s manuscripts (a useful exercise before they have begun to read the manuscript texts). Here they find a list of nine manuscripts: (1) the three volumes of juvenilia, Volume the First, Volume the Second, and Volume the Third; (2) Lady Susan; (3) Susan; (4) The Watsons; (5) Persuasion; (6) Sanditon; (7) “Plan of a Novel according to hints from various quarters”; (8) “Opinions of Mansfield Park, Opinions of Emma”; (9) “Profits of my Novels.” Even the more uninformed students will notice something striking: with the exception of Persuasion, there are no manuscripts of any of the printed novels. Students might recognize Susan as the early title of Northanger Abbey, but the manuscript is merely a small rectangular scrap, with only the words, “Susan. a Novel in Two Volumes” written on it (Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts). This scrap and the cancelled chapter of Persuasion are all that remains of what became the print novels.

Initially, the realization that no complete manuscript versions of the print novels survive may come as a disappointment to students, eager to see the development of the novels that they have or will read. However, it is possible to reverse this disappointment by inviting students to consider Austen’s purpose in writing the manuscripts that have survived. Whereas with a printed text, one can usually infer that the author intended it to be read by a (potentially) wide audience, with a manuscript, more detective work is required to discern the intended audience as well as the ways in which it actually circulated. Donald Reiman has usefully categorized modern manuscripts (i.e. those produced in the print era) as private, confidential, or public (65), and with some investigation students will find that Austen’s surviving writing fits all of these categories: her print novels address the public; her juvenilia and fair copy fiction, like Lady Susan, belong to Reiman’s middle category of the confidential; and some of her most biting satires (such as “Plan of the Novel”) and possibly her drafts, shared with only a very select few, align with Reiman’s category of the private.

In the History of England, to return to that example, we find Austen addressing her family readers (the story is dedicated to “To Miss Austen, eldest daughter of the Revd. George Austen”), whom she could expect to understand and appreciate her parody of the historical genre and her comic self-deprecation (on the title page, she describes herself as “a partial, prejudiced, & ignorant Historian,” and offers the following note: “NB. There will be very few Dates in this History”). By examining the digital surrogate of The History of England on Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts, students will also see that it appears within a larger manuscript book (Volume the Second), which is itself part of a larger collection of her youthful writing (the three volumes of the juvenilia, Volume the First, Volume the Second, and Volume the Third), which offer additional context for understanding Austen’s social manuscripts. The three volumes themselves reflect Austen’s practices of selecting and copying the juvenile writing that she wished to preserve. Like her letters, these manuscripts offer a point of entry into Austen’s social character; they also offer a glimpse of her as a working writer, something that the finished print novels do not.

Another strategy I’ve used to initiate students into the study of Austen’s manuscripts is to ask them to investigate the various physical forms the manuscripts take. Dividing them into small groups, I ask them to complete the following chart (Table 1). This exercise forces them to consider the visual/physical—rather than textual—evidence of the manuscripts. The term “draft” will likely be known to them; “fair copy” may need a brief explanation, but both terms are readily explicable through their own experiences of essay writing (as are complete/incomplete). Through this exercise, students will acquire a basic typology of modern manuscripts, distinguishing between the various categories such as drafts and fair or presentation copies, all of which are exemplified in Austen’s extant manuscripts. Most students will be uncertain about “Catherine” (given the existence of some revisions to the manuscript), will readily recognize Lady Susan as a fair copy, and the remaining three manuscripts as drafts. The question of whether the text is incomplete or not is more difficult based on visual evidence alone, but a quick reading of the final page or two will likely reveal that both The Watsons and Sanditon are unfinished, whereas Lady Susan (with its “Conclusion”) is complete.

What students will have gleaned from this short exercise is that (1) several of Austen’s manuscripts were unfinished and abandoned by her (formulating an answer as to why requires a fuller engagement with the text and her biography); and (2) several of her manuscripts are fair copies made for reading by or recital to others, including unfinished works, such as “Catherine, or the Bower.”

|

Title of Work |

Draft/Fair Copy |

Complete/Incomplete |

|

“Catherine, or the Bower” (from Volume the Third) |

||

|

Lady Susan |

||

|

The Watsons |

||

|

Persuasion |

||

|

Sanditon |

Table 1: Typology of Austen’s manuscripts

Careful examination of digitized copies of Austen’s manuscripts can help students imagine the ways literature was experienced beyond the printed page—through the exchange and collection of handwritten documents and oral recitation and performance, forms of literary transmission that were a vital part of her domestic experience. The manuscripts establish Austen’s collaborative practices (with Cassandra’s illustrations in The History of England); delineate a circle of readers (through her dedications and other personal allusions); intimate her early desire for print (through the conventions of tables of contents, dedications, indices, pagination); and demonstrate her (and her family’s) pride in the early writing, which was carefully copied and preserved.

Once students delve more deeply into the digital archive by reading some of the manuscripts of works ranging across her career, from “Love and Friendship” and The History of England to “Plan of the Novel” and Sanditon, her trenchant social and literary satire becomes apparent. Margaret Anne Doody has noticed Austen’s expressive freedom in the juvenilia, but it applies to later manuscript works as well, in which Austen’s acid tongue finds more room for play than in the print novels. Such differences suggest Austen’s careful discrimination in terms of audience—how she modulated her writing depending on whom she expected to read her works (and how she trusted these readers not to disseminate them further).

Jillian Heydt-Stevenson, Colleen A. Sheehan, and most recently Janine Barchas have excavated the ribald, risqué, and private allusions in the print novels, yet Austen appears far less constrained when working within manuscript. Indeed, even within the few surviving manuscripts it may be possible to discern different levels of intended audiences: the bound juvenilia volumes (into which Austen exercised editorial control by not copying all of her extant writing), for example, seem to imply a less circumscribed readership, as the books would likely have been on display or accessible to family members and visitors, whereas the separate sheets of “The Plan of a Novel,” a form which could be more easily secreted, seem to suggest a more limited readership (in keeping with the private digs she directs at the various suppliers of “hints,” including some family members and friends). Considering the manuscripts in relation to at least some of the print novels, which students will likely be reading as well, allows them to explore the ways in which Austen negotiated both her own familial and social circles as well as the public world of print. Many if not most of the authors of the day faced a similar problem with at least some of their texts, whether because they were socially or politically risky. Students are undoubtedly familiar with modern analogues by which they too attempt to carve out some privacy in our own Facebook age of chronic “oversharing.”

Austen’s development as a writer

Comparison of Austen’s manuscripts to one another can also provide a starting point for discussions of her compositional processes, as well as her practices of revision, ranging from sentence-level edits to large-scale reworkings of plot (as in Persuasion). Reading Austen in manuscript presents a fuller picture of her authorial range and complexity. Manuscript facsimiles provide students with stark visual evidence of Austen working and reworking her writing, directly contradicting her brother Henry’s assurance in 1818 that “everything came finished from her pen” (141). The transcriptions readily allow students to overcome some of the problems that usually present with deciphering manuscript material, particularly when the hand is difficult to read or there are heavy cancellations and emendations. The manuscripts, taken as a whole, may offer clues as to why it took her so long (over two decades) to break into print.

One of the ways I attempt to explain Austen’s difficulty finding a publisher (a fact that stuns many students) is to return to the chart students previously completed— with additional columns that address pertinent issues of style and narration (see Table 2). My belief is that Austen struggled with several elements of her fiction— with the transition from an epistolary to a narrative style, and the consequent development of the narrative voice; with the fleshing out of her heroines; and with the strong proclivity to satire—and this chart can be used to turn their attention to these issues. Students can work independently or in small groups to complete it, or it could be done together as a class exercise, with time for reflection on the significance of the patterns in reveals.

|

Title |

Draft/Fair Copy |

Complete/ |

Epistolary/ |

Narrative voice |

Main Character/ |

Satirical |

|

“Catherine” (from Volume the Third) |

||||||

|

Lady Susan |

||||||

|

The Watsons |

||||||

|

Persuasion |

||||||

|

Sanditon |

Table 2: Austen’s manuscripts, with narrative elements

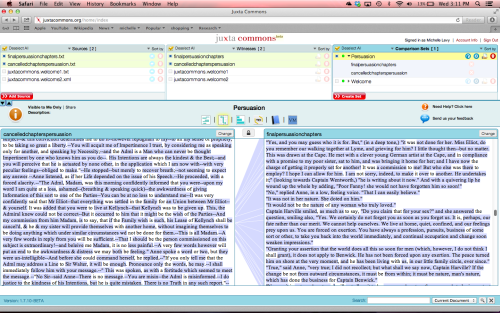

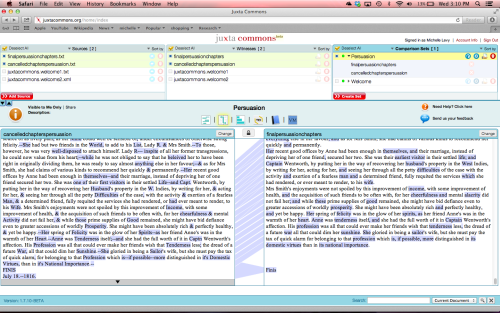

The individual manuscripts also reward careful attention for what they can tell us about Austen’s compositional habits. There are several possible pedagogical directions that can be taken. One would be to compare the two cancelled chapters of Persuasion with the final three substituted chapters. This comparison is made easier with the use of Juxta Commons—an online collation tool that allows for side-by-side comparison of the two versions. The screen shots below (fig. 1 & 2) visualize the differences between the cancelled chapters (on the left) and final chapters (on the right) with the light blue highlighting denoting all changes between the versions. This comparison contrasts the original ending (with Wentworth confronting Anne, at the Admiral’s behest, about rumors of her engagement to Mr. Elliot) to the substituted chapters (as Anne converses with Harville about women’s constancy, and Wentworth overhears). The complete rewriting that Austen does here is apparent in the sea of blue—and the connective bars between the texts allow one to scroll down to see exact points of convergence and divergence in the versions. The heavy rewriting apparent here may be contrasted with the much lighter revisions towards the end of the chapter, as seen in fig. 2.

Fig. 1 Screen shot of Juxta Commons comparison of the cancelled and substituted final chapters of Persuasion

Fig. 2 Screen shot of Juxta Commons comparison of the cancelled and substituted chapters of Persuasion

Another approach involves having students use the digitized manuscript page facsimiles and the diplomatic transcriptions to examine various authorial acts of revision within a single manuscript. Significant revisions are apparent in the working drafts of The Watsons, Persuasion, and Sanditon, and I like to begin by asking students to experiment with transcribing a page or two of one of these texts from the manuscript (which they can then check against the diplomatic transcriptions on the site).

This exercise demonstrates some of the difficulties that are involved in working with manuscript material—and involves them in thinking more carefully about the nature and effect of revisions by providing them with access to, as it were, Austen’s mind in process. Working with any of these manuscripts also draws out the difficulties in ascertaining the layers of revision and can thus lay bare the reality of these texts as truly “fluid” ones, to use John Bryant’s term.

Because this resource does not present a reading text but only diplomatic transcriptions, students have expressed frustration with the reading experience. Used to clean, edited reading texts in print anthologies and student editions, the messiness of manuscripts can come as a shock and induce frustration.

One way to acclimatize students to this messiness is by introducing them to John Bryant’s concept of the fluid text, which denies the primacy of a single moment in a text’s genesis and instead endeavors “to edit a literary work in such a way as to showcase revision, versions, and the multiple and shifting moments of intentionality throughout the creative process” (John Bryant, “Editing a Fluid Text”). In doing so, the editor: ‘presumes the validity of all moments of revision and requires an editorial approach that can accommodate and, most importantly, render readable the flow of shifting intentions. This new focus on revision requires editors to develop strategies of displaying texts to reflect a work’s textual fluidity; at the same time, readers need new strategies in how to read revision and versions (John Bryant, “Editing a Fluid Text”).’ This understanding of textuality is encouraged by reading texts in a variety of forms (such as digitized manuscript facsimiles and diplomatic transcriptions), though as Bryant notes even a diplomatic transcription can hide layers of revisions contained within a single manuscript. While his digital edition of Melville’s Typee begins to untangle these multiple stages of revision, with Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts it is up to students to discriminate between different kinds of editorial changes and to work out a possible sequence of revisions.

Returning to the pages they have transcribed, students can begin to parse different types of revisions, and to conjecture as to when and why they were made. With attentive reading, they begin to distinguish between different types of revision:

- those immediate second-thoughts made at the original moment of composition (often identifiable by their placement on the page—on the same line as the cancellation); and

- those made at a later point (often identifiable by interlinear or marginal additions/corrections; by changes in ink or hand; by insertions on separate sheets, pasted in (as in Persuasion) or affixed by pins (as in The Watsons) to hide or extend a reworked passage).

Students, having experimented with transcription and carefully examined some local sites of revision, will thus be in a position to delve more deeply into the significance of Austen’s writing process. For example, the three pinned additions to The Watsons (which may be seen here, here, and here; and Later Manuscripts, 336-7, 353-5, and 369-70) all involve a fleshing out of character by reworking and expanding dialogue—with the substituted Persuasion chapters offering similar examples. I have argued previously that a study of the manuscripts reveals that Austen appears to develop her heroines at a later stage of the compositional process, and these additions provide evidence of this pattern of revision (Levy 1023-25). Her revisions offer intriguing glimpses into her working method and what mattered to her—how she corrects herself to get her facts right, or to develop characters more precisely.

While Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts invites this kind of careful review of the manuscripts and transcriptions, it does not support more sustained reading, whether of the facsimiles alone or alongside the transcriptions, for a few reasons. Although the editors are “unapologetic in saying that the website contains objects to be used,” as opposed to texts for continuous reading, there is no reason the choice has to be dichotomous (Sutherland and Pierazzo 209). Allowing users to view the diplomatic transcriptions independently, apart from the manuscript pages, could enhance continuous reading. While this wouldn’t prioritize the manuscript to the same extent, it would provide more flexibility for students. Some of these manuscripts are lengthy (Lady Susan is 158 pages; The Watsons is 85 pages; the two cancelled Persuasion chapters are 32 pages; Sanditon is 136 pages), and it is a tedious process to click on each page and wait for it to load (the delay being a function of the high quality of the images, which are being loaded alongside of the transcriptions). In contrast, The British Library’s virtual edition of Austen’s The History of England uses a “Turning the Pages” interface, which allows the user to move more quickly through the document, as a new page is immediately “turned” with a simple click.

Another way in which Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts could be vastly improved is with a download function—now available on many other sites—that would allow a complete text (or portion of it) to be viewed (and saved, and printed) as a pdf. (Of course, this would come at the cost of image quality, but it is a trade off worth making for ease of reading).

In the absence of such a function, and given the difficulties of prolonged screen reading, it may be beneficial to assign students a printed text of the manuscript writing. Fortunately, with the release of Broadview’s Jane Austen’s Manuscripts in 2012, there is now a reasonably priced and meticulously edited collection of most of her fiction manuscripts available for student use.

The Broadview edition provides reading texts, and it is a fascinating exercise to have students compare these to the online diplomatic transcriptions so they may see the editing decisions that have been made to create a clean reading text. Having worked with the manuscripts, students will be in a better position to debate the importance of having diplomatic transcriptions in addition to reading texts (at present, students have the diplomatic transcriptions online, and reading texts in print).

Comparing manuscript to print also invites discussion about how Austen’s texts may have been edited by publishers and printers (as well the changes she made to Sense and Sensibility and Mansfield Park for their second editions, published in 1813 and 1816, respectively). Students may be surprised by the degree of editing that appears to be left in the hands of the printer, who, at the very least, appears to have normalized Austen’s spelling and introduced paragraph breaks. And students will be intrigued by the recent controversy that has erupted over claims made by Kathryn Sutherland (the editor of Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts) that Austen’s prose style (for which she is so celebrated) owes much to the interventions of an editor, possibly William Gifford.

Finally, the three short manuscripts (so short they could even be read during class), “Plan of a Novel,” “Opinions of Mansfield Park, Opinions of Emma,” and “Profits of my Novels,” can offer valuable insight into Austen’s self-perceptions as a writer. Together, they paint a portrait of an author eager for material and critical success, but also unwilling to suffer fools. “Plan of a Novel” and “Opinions” in particular offer some of the most prolonged reflections on the writing and the reception of her novels. These manuscripts could be usefully compared to the few other meta-fictional statements we have from Austen—the “Advertisement” to Northanger Abbey and Chapter 5 of that novel; the letter to the publisher Benjamin Crosby dated 9 April 1809, under the pseudonym Mrs Ashton Dennis, allowing her to close her letter to “I am Gentlemen &c &c MAD.-” (Le Faye, 182); and the letters to her niece, Anna Lefroy, in 1814-1815 (Later Manuscripts, 214-225)—reflecting the negotiations and compromises that Austen was compelled to make with her readers throughout her life.

The nature of physical and digital archives

Involving students with Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts further provides opportunities to discuss the nature of the surviving archive record, both in its physical form and its most recent virtual incarnation. Students will have already learned that Austen did not keep any of the drafts or fair or press copies of her novels, but why this is the case warrants some consideration. It seems that many novelists of the period did not keep their manuscripts after their novels were printed, though some (including Walter Scott) did (Later Manuscripts, xlv). Why the practices relating to fiction manuscripts are so different than poetic manuscripts, which were often retained, warrants some scrutiny. It is also perhaps surprising that the manuscripts of Austen’s two posthumously published novels (Northanger Abbey and Persuasion) were destroyed, when their value may have been more apparent.

The survival and dispersal of Austen’s manuscripts also offers a fascinating narrative of the familial and cultural significance of manuscript artifacts. Dispensed as mementoes by Cassandra to various family members upon her death in 1845, and subsequently, via auction, to public and private collections in the 1920s, the story of the dissemination of Austen’s manuscripts, and their subsequent publication, also invites attention. The way these manuscripts gradually entered the public eye—first with a mention in her nephew’s Memoir of 1870, then incrementally published in expurgated form in the second edition of the Memoir in 1871, and more fully and accurately in the decades that followed—offers yet another strand in the rich reception history of Austen’s manuscripts that could be explored more fully by students in their own research. Students respond with interest (and sometimes indignation) to discovering how disparagingly her juvenilia was treated by her earliest editors—her nephew and later R.W. Chapman—who infamously dismissed all of Austen’s manuscript works as “Minor.”

The remediation of these manuscripts, first in print facsimiles and now in digital form, reflects a long-standing effort to bring them out of the domestic and into the public realm, but the actual manuscripts are still very much under lock and key at various institutions. (A librarian at the British Library informed me that their holdings of Jane Austen’s fiction require the highest level of clearance to access). While students (and indeed most scholars) are unlikely to come into contact with an actual Austen manuscript, they are instinctively aware of the differences, as a three-dimensional object represented on a two dimensional screen, the digital environment necessarily flattens and disables any physical interaction with the original. Videos of Kathryn Sutherland presenting Austen’s manuscripts (produced by the Bodleian and the British Library) help to mitigate the reductive nature of digital remediation by capturing the scale of the manuscripts in relation to the human body, and presenting them in their three-dimensionality (see Online Resources and Tools, below).

The affordances of full-color, high-resolution digital images are many, for they can enhance what may be seen with the naked eye, creating in effect “a digital magnifying glass” allowing for inspection of minute details: variations of ink color and line thickness, and even the minutiae of abraded paper and binding thread (Griffin 60). What does this level of detail allow students and scholars to see, and how might these visual cues be meaningful? I have already suggested one of the reasons why variations in ink may be important—to detect different moments in the revision process. Being able to view her hand-made notebooks (in The Watsons and Sanditon), though changed by modern conservation efforts, demonstrates the handiwork that went into her writing. Simply being able to see the paper, ink, and type of support in such detail provides an occasion to teach students about the mechanics of writing in the period (Hurford).

Students can also be invited to consider what else they can do with a digital archive. One benefit of the encoded transcriptions is that they enable full-text searching. Students are likely familiar with the benefits of keyword searching of born-digital websites and many digitized printed texts (those that have been subject to Optical Character Recognition [OCR] software and hence are searchable), but this kind of functionality is rarely available with digitized manuscripts, which are not machine readable in the same way as print. The use of search functionality has become such a ubiquitous academic practice for students and researches alike that we rarely scrutinize how and why we use it—and how it differs from the ways in which we search printed material (such as via indices, scanning, and annotation). What kind of research questions can we devise with this capacity to search accurately and in a matter of seconds through hundreds of transcribed manuscript pages? To ask a question that perennially arises in the digital humanities, what is the value added beyond what we can do with the original manuscript or print sources?

Students can also be called upon to evaluate how well digital archives are designed for their purposes and become critical users of the technological interfaces they are increasingly being asked to use in our courses. I ask students to identify one aspect of a digital resource that worked well, and one other that didn’t. Collectively, students responded enthusiastically to many features of the site, but they can also be sharply critical, and together have noted the following impediments to usability: no e-table of contents for the juvenilia; no ability to zoom when viewing the diplomatic display alongside of the facsimile; no ability (without opening a separate browser window) to compare manuscripts—a somewhat serious flaw given that one of the aims of the site is to enable “simultaneous ocular comparison of” the physically separated manuscripts; no ability to read the transcriptions alone; no reading texts; no ability to download complete documents; no aligning of facsimile and transcription—scrolling down one does not automatically bring the other with it. Although some of these objections are more minor than others, my own sense is that the site could be better adapted to encourage prolonged reading and facilitate comparisons between manuscripts.

An additional limitation of the site, in my view, is that none of the encoding is shared. It would be extremely helpful, for teaching purposes, to provide students with even a brief glimpse of the skilled interpretative work that is required to produce the precise diplomatic transcriptions that are rendered on the site.

Further, although the site is open-access, it is not “a social edition,” and thus offers no ability to contribute to conversations about, or scholarship on, the text.

Such opportunities may be important motivators for students, helping them “to take their work more seriously and to increase their engagement” (Norcia 105). It is possible for instructors to devise other means (such as class websites) for students to publicize their work, and I have recently experimented with having my advanced undergraduate and graduate students prepare their own digital editions of some of Austen’s manuscript works.

These projects can present their own challenges—intellectual and technical—though I have found my students are keen to experiment with modes of research beyond the essay, including new digital forms of dissemination.

Another helpful exercise, if students have been assigned a print edition of the manuscripts such as Broadview’s, is to ask them to compare it to a digital edition. What are the merits/demerits of the way each medium reproduces Austen’s text? Though it styles itself as a digital edition, Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts is devoid of the editorial apparatus usually found in critical editions (a scholarly apparatus is promised in a forthcoming “print edition” that “will be enhanced by richer annotation, discursive essays on the genesis and composition of the manuscript works.”) In particular, Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts lacks an introduction, and the annotations and contextual material that are found in the Broadview edition. As it stands, what the digital and the print treatments of Austen’s manuscripts offer are bifurcated: one provides reading texts and a critical apparatus; the other diplomatic transcriptions, page images, and detailed descriptions of the manuscripts, as well as discussions of provenance and conservation measures. Students can scrutinize the choices that have been made for each kind of edition, weigh the pros and cons of each, and consider the reasons that may lie behind what is included and omitted from each edition. Recent findings about the limitations of screen reading may mean that this hybrid (print and digital) approach is ideal: students long for and need the deep engagement that it seems only reading paper and ink can provide, and yet they can benefit enormously from access to rare materials that can only be made available digitally.

Conclusion

I have outlined some of the many directions that teaching Austen’s manuscripts can lead—but the best justification for introducing a selection of her manuscript texts is the pleasure they afford, and the rewards students reap in acquiring a more capacious understanding of her as an author. In reading her manuscripts, we find a writer different from that of the six printed novels, one who is more playfully meta-fictional about writing and contemporary literary genres; more caustically embittered, particularly about the status of women; more penetratingly satirical about the world in which she lived; and more willing to touch directly both on day-to-day life (the extended sequence on the preparation of “Cocoa & Toast” in Sanditon offers one delightful example) and a wider array of social classes.

Investigating the differences between Austen’s appearance in script and print is a worthwhile and fruitful pedagogical endeavor—and for the first time these conversations may be had in our classrooms, with ease and little expense, because of the superb digital and print editions of Austen’s manuscripts that are now available to us.

Online Resources and Tools

Works Cited

2. New York: Norton, 2012. Print.