The mediation of antique vases was part of a larger project that domesticated Greek and Roman classicism so that it could be claimed as part of English heritage. The Portland Vase serves as a useful example of Romantic-era management of antiquity as both economic and cultural capital, and it points to a multifaceted mediation of ancient artifacts that crosses and complicates the categories of art and craft. While it is true that reproduction has produced an aura of originality around the ancient Portland Vase, a priceless Roman artifact housed in the British Museum, there was a time in the 1790s when the original had less cultural authority than its copies. In fact, the copies had so much authority that they were taken up by artists, who preferred them to the original Vase. Raymond Williams argued that the movement from individual to institutionalized patronage of the arts occurred concomitantly with the professionalization of cultural producers. Terms like "artist," "artisan," and "craftsman," according to Williams, came to signify the ways in which made objects were mediated through the market, their institutional status, their means of production, and their intended or perceived purpose (44-52). Taking up this unstable relationship between art and craft, I want to consider the Wedgwood copies of the Portland Vase as well as two instances where Wedgwood's factory-made copies were celebrated in genres that can comfortably be described as "high" art—or at least genres we agree are not craft. Those examples are Erasmus Darwin's inclusion of the Vase in his poem The Botanic Garden and Benjamin West's oil-on-paper study for Manufactory Giving Support to Industry. Both Darwin's poem and West's painting are dated 1791, the year after Wedgwood first displayed his jasperware copies of the Portland Vase. There are several reasons Darwin and West's artistic tributes prefer native copies over the Roman original. Foremost, the copies declare English genius. Josiah Wedgwood invented and perfected a clay process he named "jasperware," which was well suited for the imitation of cameo glass—but the copies served the added function of domesticating the Continental Other, of making the distant past into a consumable product of the present.

More to Williams' point, the inclusion of his copies of the Vase in these works of art points to Wedgwood's ability to leverage competing institutions whose missions were to promote contemporary art on the one hand and antiquity on the other. London artists struggled for legitimacy and market share, and classical antiquarians were often also art collectors and connoisseurs. The classical antiquarians who sought to guide artists' taste through publications like those funded by the Society of Dilettanti were also likely collectors of the art they "encouraged." English artists maintained a complex and sometimes vexed relationship to collectors, who were accused of preferring the old over the new. William Hogarth acknowledged this tension in several satiric prints, including his 1761 Time Smoking A Picture, in which Time, having lost his usual robe, looks rather like a fleshed-out angel of Death. This Father Time sits on broken antique statuary, his smoke varnishing an Old Master painting into obscure ruin as his sickle pierces the canvas. While most English artists genuinely shared a taste for classical art, they needed collectors to support them by purchasing contemporary, native artwork. Practically, this meant that both artists and antiquarians had a stake in saying what counted as art. Pierre Bourdieu has argued that competing producers of fine art "consecrate and underscore critical differences" in order to highlight their own theory of taste; but I want to show that Wedgwood's apotheosis occurred because he minimized the differences between the theories of copying put forth by antiquarians and artists (Bourdieu 51, 65).

* * *

Before it was known as the Portland Vase, the so-called "Barberini Vase" was a tourist destination, and the Vase has been included in antiquarian accounts of classical antiques since the late sixteenth century (Jenkins and Sloan 187). The Barberini family, whose fabulous art collection was housed in a family palazzo designed by Bernini and completed in 1633, owned the Vase from the year 1626, three years after Maffeo Barberini was named Pope Urban VIII, to somewhere around 1780, when Donna Cordelia Barberini-Colonna sold it to a Scotsman to pay off her gambling debts. Over the course of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the Palazzo Barberini was a frequent stop for British Grand Tourists visiting Rome (Walker 21). However, seeing the Vase in person was not a prerequisite for writing about it. The antiquarian Pierre d'Hancarville was author of the tremendously influential Antiquités Etrusques, Grecques, et Romaines tirées du Cabinet de M. Hamilton (hereafter AEGR), which lavishly displayed the collection of Sir William Hamilton, who would eventually bring the Vase to London. Volume II of AEGR, brought out in 1770, acknowledges the Vase's fame, confirms the prevailing notion that it was a funerary urn containing the ashes of the Emperor Severus, and takes note of its unique composition: "it is a sort of paste of two coats of colours, of which, one detatching itself from the other, by the difference of its tint, is worked with the turn, in the same manner as the finest Cameos" (2:74). The passage goes on to say the Vase is housed in the Palazzo Farnese, not the Palazzo Barberini, suggesting that either d'Hancarville had confused its location or that the Vase had already been moved as a result of Barberini family insolvency. Hamilton did not apparently see the Vase until a decade later, after Donna Cordelia had sold it to James Byres, the aforementioned Scottish antiques dealer (Jenkins and Sloan 187). Nevertheless, he would have been aware of the Vase through numerous antiquarian publications.

Hamilton was the English Envoy to the Court of Naples from 1764 to 1800. His acquisition of the Portland Vase sometime in 1782 was probably profit-driven, motivated by the expense of his collecting and publishing efforts. He seems to have acquired the Vase on a £1000 bond with a 5% interest rate, suggesting he must have planned to dispose of it with relative haste (Jenkins and Sloan 187). Hamilton's speculation clearly paid off; by January of 1784 it was in the hands of the Duchess of Portland, who bought it for 1800 guineas.

Hamilton's collection, the publication of AEGR, and his location in Naples consolidated his authority on matters of antiquarian taste, and he was interested in encouraging English artists and artisans to take up classical design in contemporary production. D'Hancarville warns artists away from simply copying the style of their masters, urging them instead to attend to the principles of classical art. The introduction to the first volume of AEGR explains that part of the book's purpose is to serve as a collection of superior models "in order that the Artist who would INVENT in the same stile, or only COPY the monuments which appeared to him worthy of copied may do so with as much truth and precision as if he had the Originals themselves in his possession" (1: vi). And indeed, engravings from the work served as models for contemporary paintings.

However, d'Hancarville made sure readers understood it was not only painters he and Hamilton had in mind. The text goes on to assert: ‘[W]e make an agreable [sic.] present to our Manufacturers of earthen ware and China, and to those who make vases in silver, copper, glass, marble &c. Having employed much more time in working than in reflexion, and being besides in great want of models, they will be very glad to find here more than two hundred forms, the greatest part of which are absolutely new to them.... (1: xx)’ The arrogant tone of the introduction, especially in statements like those quoted above, makes it easy to see how artists and artisans might complain of antiquarian interference in matters of their own professional authority. As organizations like the Society of Dilettanti and later the Committee of Taste, which included the outspoken antiquarian Richard Payne Knight after 1802, claimed to know art better than institutionally sanctioned fine artists did, authority over matters of taste was a source of conflict.

Josiah Wedgwood was less interested in arbitrating taste than he was in ensuring he was on the right side of it; a businessman who wanted to produce and profit on the sale of pots, he recognized Hamilton's importance and his authority on matters of taste. Wedgwood was said to have his own problems with fine artists, and in a letter dated 13 September 1769 he complained of their "coxcombical manners" and said he "would rather Man for Man have to do with a shop of Potters than Painters" (120). Wedgwood's library was filled with antiquarian publications, and he had London connections that offered access to engraved proofs of AEGR well before the volumes were brought out (Irwin, “Design” 289). In fact, Wedgwood's letters offer evidence that English fine artists did compete with antiquarian prints. In 1776, he wrote to his business partner in London attempting to cancel an expensive commission to John Flaxman, suggesting that engravings of ancient gems might serve as acceptable models for "little more than five shillings" (Irwin, “Design” 289). Under Hamilton's influence, Wedgwood had gone so far as to name the Staffordshire works he began construction on in 1768 “Etruria,” in honor of the pots Hamilton collected, which were thought to be of ancient Etruscan origin.

As far as the Portland Vase was concerned, Hamilton maintained his economic and cultural interest by retaining the right to display it at the Society of Antiquaries and even to copy it, despite its sale to the Duchess of Portland. Though the Vase was no longer his, he nevertheless commissioned Cipriani to make drawings that were subsequently made into copperplates by Francesco Bartolozzi (Wills 197). The prints were published by John Boydell, who in 1786 was still in Cheapside but was already advancing his scheme for the Shakspeare Gallery that would move his expanded operations to Pall Mall. The Society of Antiquaries noted in its minutes of 11 March 1784 that "having been for many Years in the possession of that Noble [Barberini] Family & considered by them, & all Travellers of Taste & Judgement, as a Cimelium of extraordinary Curiosity & Value," it was presented to them by Hamilton with no indication that he was not the owner of it (qtd. Wills 198). Thus the Vase accrued English cultural capital as it was remarked upon by important institutional arbiters of taste at both the Society of Antiquaries and the Royal Academy.

The president of the Royal Academy, Sir Joshua Reynolds, also endorsed the Vase before Josiah Wedgwood's involvement with it. After the Duchess had secretly owned it for but a short time, she died. Upon her death, the contents of her extensive collection were put up for auction. The Vase was purchased by the Duke of Portland, the Duchess's third son. Horace Walpole wrote, "In August of 1786 Sir Joshua spent a few days at Bulstrode with the Duke of Portland, whose adviser he seems to have been in his purchase of the famous Vase for a thousand pounds" (qtd. in Wills 201). In fact, the sum of purchase was somewhat more than Walpole indicates, but Reynolds' authority did encourage the Duke to keep the Vase in the family—and it would be Reynolds as well as Hamilton on whom Josiah Wedgwood would rest his own authority as he transformed the Vase from a singular work of fine art into a reproduced commodity. Its success went beyond the quality of the copy. Wedgwood's ability to garner high-profile endorsements from both antiquarians and the institutionally sanctioned London art world put him in an excellent position before work on the copies ever began.

More generally, Wedgwood used both the whims of domestic fashion and export markets to expand his name and business. Marx might have been thinking of Wedgwood when he noted that industrialization stimulated the creation of new markets as well as "more thorough-going exploitation of the old ones" (478). Josiah Wedgwood was acutely attentive to the taste of the consumers he served, and as early as the 1770s, he recognized that overproduction called for a larger market in order to sell existing stock: "& nothing but a foreign market ... will ever keep [our stock] within a tolerable bounds" (qtd. in McKendrick, “Marketing” 426). He had initially made a name for himself making creamware, which was to be split off into his lines of "useful" wares, as opposed to the "ornamental" wares that his partner Thomas Bentley, a cloth manufacturer with a classical education, encouraged Wedgwood to develop. Wedgwood's letters indicate his deference to Bentley in matters of taste. In one particularly telling example, Wedgwood points out his dependence on Bentley's knowledge of Continental and Antique fashions. In September of 1769, he wrote: ‘If you continue to write such letters as the last [detailing classical fashions] there is no saying where our improvements will stop. I read it over, & over again, & still profitt by ever repetition of your agreeable lessons. ’ ‘And do you really think that we can make a complete conquest of France? [...] My blood moves quicker, I feel my strength increase for the conquest. Assist me my friend, & the victorie is our own ...I say we will fashn. our Porcelain after their own hearts, & captivate them with the Elegance & simplicity of the Ancients. But do they love simplicity? Either I have been greatly decieve'd, or a wonderful reformation has taken place amongst them. French & Frippery have jingled together so long in my ideas, that I scarcely know how to separate them, & much of their work which I have seen cover'd with ornament, had confirmed me in the opinion. (Letters 77)’

Wedgwood was willing to be directed, but he also understood how to use his relationship to Hamilton. As he was negotiating access to the Portland Vase, he also instructed Bentley to show wares Hamilton "& a few other Connoisieurs not only to have their advice but to have the advantage of their puffing them ... as they will, by being consulted, and flatter'd agreeably, as you know how, consider themselves as sort of parties in the affair & act accordingly" (qtd. in McKendrick, “Marketing” 414). Wedgwood's genius lay partly in this deference, partly in his brilliant ability to exploit what he learned, and partly in his capacity for applying scientific experiment to the process of manufacture. Jasper was the only real invention of Josiah Wedgwood in terms of clay composition, and he worked for years perfecting it (Buten 139).

He was looking for a clay that was easily colored and would hold a sharp, detailed relief image when fired, in order to replicate the aesthetic of bas-relief and cameo glass.

Wedgwood wasted no time in congratulating the Duke of Portland in his acquisition of his vase at auction. Three days after the sale, 10 June 1786, Wedgwood and the Duke had drawn up an agreement whereby Wedgwood borrowed both the Vase and a glass cameo from the same auction lot in order to produce accurate copies (Mankowitz 20). Wedgwood understood what he had. Later on the 24th of June, Wedgwood wrote a very long letter to Hamilton.

In the letter, he explained that he had begun "to count how many different ways the vase itself may be copied to suit the tastes, the wants & purses of different purchasers," explaining that he could envision making cheap, all-white biscuit copies for artists, copies with a painted blue background for middle-class collectors, and polished jasperware copies for the richest collectors. At the same time, he was acutely aware of costs, worrying to Hamilton that it would take a team of the best engravers and modelers, who would have to be bought out of their current employments—and it would cost "£5000 for the execution of such a vase, supposing our best artists capable of the work." In the end, he used his own labor and the labor of the modelers already employed by the factory, and by 1790 he had garnered twelve subscriptions, which helped defray some of the costs (Mankowitz 31).

In the same letter of 24 June, he also asked for advice in terms of improving what he saw as imperfections in the Vase. Perhaps Wedgwood saw in AEGR what Hamilton himself could not. Hamilton's book had promised accuracy, but in the process of translating three-dimensional artifacts onto engravings on paper, it idealized ancient vases into neoclassical versions of themselves (Coltman). These inaccuracies were not ungoverned error. Rather, accuracy was mediated through a network of the visual materials produced in contemporary antiquarian publications, which on the whole represent what we might think of as a "way of seeing" that idealized and remade the antique.

Wedgwood, in keeping with AEGR's prescription to manufacturers, had initially tried to copy the Vase from prints. Upon access to the original, he acknowledged the significant gap between antiquarian engravings and the real artifact: ‘When first I engaged in this work I had Montfaucon only to copy, I proceeded with spirit, and sufficient assurance that I should be able to equal, or excel if permitted, that copy of the vase; but now that I can indulge myself with full and repeated examinations of the original work itself, my crest is much fallen, and I should scarcely muster sufficient resolution to proceed if I had not, too precipitately perhaps, pledged my self to many of my friends to attempt it in the best manner I am able. Being so pledged, I must proceed, but shall stop at certain points till I am favored with your kind advice and assistance. (Mankowitz 22)’ Wedgwood's initial reliance on paper vases and his crestfallen reaction at seeing the original tells us first that he was aware of the commercial potenital in the Barberini Vase before it came to London—but more importantly, it registers the gap between the usual procedure of copying from copies and the unmediated confrontation with what Keats in his 1816 Ode would call the "unravished bride," the unmediated Vase, with all its unyielding meaning.

In turn, manufacturers were not simply copying antiquity from prints; they sought to further improve upon it. Moreover, Wedgwood saw it as his purview to improve the taste of consumers as much as Hamilton had improved the taste of manufacturers. Nevertheless, in reply Hamilton wrote: "You are very right in there being some little defects in the drawing; however, it would be dangerous to touch that, but I should highly approve of your restoring in your copies what has been damaged by the hands of time" (qtd. in Wills 201). This exchange demonstrates not only that Wedgwood deferred to authority on matters of taste but that Hamilton could not see that antiquarian engravings irrevocably changed what they mediated or that his own publications were as guilty of inaccuracy as were the English artists whose work they sought to guide.

At the same time, of course, London artists also sought to guide and improve the taste of the nation. Joshua Reynolds' annual addresses to students of the Royal Academy were published as his widely read Discourses on Art. He wrote in his very first Discourse, delivered 2 January 1769 as the inaugural lecture of the newly founded Royal Academy, that the fine artists of his new institution would, by virtue of their own superior taste, serve "the inferior ends" of manufactures while remaining above the commercial fray (13). While Discourse I is clearly less directive than AEGR's introduction when it comes to "our Manufacturers of earthen ware and China," its tone regarding the inferiority of the commodified goods is consistent. Professional artists and their institutions assumed their superiority over the manufacturers as comfortably as the antiquarians did over them. Whatever Wedgwood may have thought of these "coxcombical manners," he negotiated the situation with his usual deference and finesse.

The genesis of Wedgwood's question to Hamilton is suggested by Reynolds' sixth Discourse, he argues that artists should both copy from antiquity and labor to improve upon their subjects: "He who borrows an idea from an ancient ... can hardly be charged with plagiarism ... But an artist should not be contented with this only; he should endeavor to improve what he is appropriating for his own work" (107).

While d'Hancarville and Hamilton were telling artists to steer clear of their masters' prejudices and return to the principles of the ancients, those very masters, Reynolds among them, were advising artists to take the ancients as a starting point, and to improve upon them by remaking them based on the modern principles presented in the Discourses. Wedgwood's philosophy on copying deftly incorporated Reynolds's position while citing Hamilton as its source. As Wedgwood explained on 28 June 1789 to Erasmus Darwin: ‘I only pretend to have attempted to copy the fine antique forms, but not with absolute servility. I have endeavored to preserve the stile and spirit or if you please the elegant simplicity of the antique forms, and so doing to introduce all the variety I was able, and this Sir W. Hamilton assures me I may venture to do, and that is the true way of copying the antique. (Letters 307)’ On 15 June 1790, Reynolds wrote of the fifteenth copy of the Vase, which he examined personally, "I can venture to declare it a correct and faithful imitation, both in regard to general effect, and the most minute detail of the parts."

Wedgwood's hybrid marketing technique owed more to the London art world than to its mere endorsement of his product. Wedgwood by this time had begun to mark his pottery and issue descriptive catalogues as well, which was unusual for a manufacturer (Buten 9). These catalogues link him to the art field in both their physical appearance and their size, and, perhaps more importantly, in the way they connected the object described in the printed catalogue to a metropolitan gallery space where those objects were on display (in this case Wedgwood's Soho showroom). These ties to fine art, in turn, strengthened the legitimacy of his Portland Vase copies.

Like Boydell, another great cultural entrepreneur of the 1790s, Wedgwood used a combination of print advertisement, ticket sales, and catalogues to generate excitement and anticipation over an end product that took years to produce. Boydell, a London Alderman, was the proprietor of the Pall Mall Shakspeare Gallery, which commissioned paintings for display in the gallery and sold engraved facsimiles of those paintings. Just as Boydell printed catalogues and sold subscriptions to his high-profile engravings of scenes taken from Shakespeare, so Wedgwood sold subscriptions to his early Portland Vase copies, used gallery-style showrooms, and printed catalogues.

The analogy between Wedgwood and Boydell is worth pursuing in this instance, since both trafficked on the fame of an original to sell copies. Whereas Boydell's engravers contemporary painted canvasses onto copper, Wedgwood transformed ancient artifacts into contemporary jasperware. Their tactics were strikingly similar—and so were their overreachings. Wedgwood garnered twenty subscriptions for his first edition of the Portland Vase with a final price between thirty and fifty guineas each (Keynes 248). As early as 1786, he had planned the subscriptions, as he wrote to Hamilton: ‘Several gentlemen have urged me to make my copies of the vase by subscription, and have honored me with their names for that purpose; but I tell them, and with great truth, that I am extremely diffident of my ability to perform the task they kindly impose on me; and that they shall be perfectly at liberty, when they see the copies, to take or refuse them; and on these terms I accept of subscriptions, chiefly to regulate the time of delivering out the copies, in rotation, according to the dates on which they honor me with their names. (Letters 296)’ In spite of the technical and aesthetic success Wedgwood ultimately achieved, half the subscribers chose not to take the copy they had agreed to pay for (Keynes 248). As with the Boydell Shakspeare Gallery, subscriptions served to drum up public interest, inasmuch as prominent members of society signed on and subscription lists were widely circulated, but in the final analysis they failed to bring about financial success. In spite of their fame and acclaim, both the Shakspeare Gallery and the Wedgwood Portland Vase copies were ultimately financial failures, although as public spectacles celebrating the possibilities of commercial art, both were tremendously successful. Although both Boydell's and Wedgwood's designs for a financial payoff may have been thwarted, neither man's firm was ruined by his venture. Alderman Boydell died around the same time his Shakspeare Gallery stock was sold off by lottery, but the firm went on with his nephew Josiah Boydell at the helm. In Wedgwood's case, the fame of the undertaking and the invention of jasperware far outweighed the fact that so few copies of the Portland Vase actually sold. The popularity of the Portland Vase generated traffic in Wedgwood showrooms, which multiplied across London and the Continent.

Ultimately, Wedgwood copies of the Portland Vase upstaged the Vase itself, demonstrating Wedgwood's success in doing precisely what engravers of the Romantic period could not quite manage: producing the notion that a reproduced, manufactured product that many hands had labored to produce was worthy of the consecrated status of art object. Boydell's attempts to transform English engravers into household names went only as far as William Woolett, who engraved an incredibly successful print of West's Death of General Wolf for Boydell before he opened the Shakspeare Gallery (Bruntjen 36). It is likely that his success at making Woolett a household name planted a seed of the Shakspeare Gallery, a gallery that sold English Engravings of English paintings on specially made English paper. However, the idea that an engraver might be as much an artist as a painter did not sit well with painters, who (with the notable exception of Benjamin West) regularly blocked engravers' attempts at full membership in the Royal Academy over the course of the Romantic period. English pots, made of English clay, however, didn't have to compete with living artists and their ideas about originality. In copying the antique, Wedgwood did not compete with any living artist; he was free to scoop up his native clay and make from it a new body, cast from the ancient legacy of this Roman vessel.

* * *

Josiah Wedgwood made his friend Erasmus Darwin a present of the first perfected copy of the Portland Vase (Keynes 248). In turn, some seventy-seven lines of Canto II of Darwin's “The Economy of Vegetation” are devoted to ceramics, with a view to celebrating Wedgwood as the culmination of some two millennia of the art form's development. The Canto, addressed to the elemental Gnomes of Earth, mentions "Portland's mystic urn" in the context of a list of Wedgwood's accomplishments, and it also refers readers to a four-page endnote, which interprets the images on the surfaces of the Vase as depicting the Eleusinian mysteries. As a whole, Darwin's second Canto celebrates various geologic discoveries and phenomena, including the section that narrates the development of pottery from China to Etruria to Wedgwood's Stoke-on-Trent works. The Gnomes:

[P]leased on WEDGWOOD ray your partial smile,A new Etruria decks Britannia's isle.— (303-4)

With such an endorsement from the spirits of the earth, Wedgwood's "bold Cameo speaks" and his "soft Intaglio thinks" (310). Wedgwood, "Friend of Art," that he is, has the authority to copy "the fine forms on PORTLAND'S mystic urn" (313, 320). The Vase's decorations are ekphrastically described in lines 321-340, but the copy is given far more imaginative space than is the original. After all, there is no mention of a Roman artist or even a cameo glass body. The Gnomes of this Canto are concerned with Chinese, then Italian, then English clay—but never Roman glass.

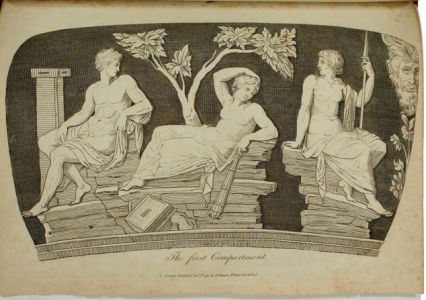

Darwin evidently felt that a visual representation of the Vase was important enough to delay publication of his Botanic Garden until his publisher, Joseph Johnson, could supply engravings of it (Brooks 152). Darwin had wanted to include the engravings Hamilton had commissioned when it was initially brought to London. Perhaps it was natural that Darwin would have thought of Bartolozzi's recently made Portland Vase engravings as he wrote his poem, but Hamilton held the copyright on Bartolozzi's engravings, so Johnson had no choice but to hire someone to re-engrave the Vase. There is no evidence that his employee, William Blake, who Johnson assured Darwin was "certainly capable of making an exact copy of the vase," ever actually examined the original (qtd. in Keynes 251).

Blake certainly did ask to see Bartolozzi's engravings, however, in July of 1791, when Blake began work on new versions of the illustrations (Keynes 251). Both Blake's pictures and Darwin's poem relied on prints, textual analyses and Wedgwood copies—copies of copies, cycled over again through the "Mill & Machine" of English presses.

Fig. 1 (left) Engraving by William Blake, First Compartment of the Portland Vase. Engraving from Erasmus Darwin, The Botanic Garden (London: 1791). Courtesy of the Hunt Botanical Institute.

Fig. 2 (right) Engraving by William Blake, The Portland Vase. Engraving from Erasmus Darwin, The Botanic Garden (London: 1791). Courtesy of the Hunt Botanical Institute.

Blake's illustrations of the compartments look enough like Bartolozzi's to suggest that Bartolozzi was probably Blake's only source. One notable difference between Bartolozzi's 1786 engravings and Blake's copies of them is the introduction of fig leaves, which must have been Johnson's emendation. Darwin himself would have been perfectly happy to use Cipriani's designs, which, of course, contained fully nude male figures. In 1786, the Vase, which had been on display at the Society of Antiquaries and was now the recent acquisition of the Duke of Portland, was an antiquarian art object; but reading audiences were a more diverse lot than the connoisseurs who might have been expected to purchase a folio of expensive prints. Johnson's care in protecting readers from visual indelicacy shrewdly anticipates a more widescale practice of "improving" classical antiquity to make it palatable for an array of British readers.

Such a practice was sanctioned by Reynolds' authorization, in the Discourses, to improve upon ancient designs, and this particular improvement was a wise decision, given the number of editions the book went through.

In Darwin's note, the ekphrastic description of the Vase contains no information that could not be gleaned from the engravings. Using a teleological narrative that starts in ancient China and arrives at Britannia's Etruria, Darwin implies that Wedgwood represents the apex of pottery's technological development. In case the verse leaves any doubt in readers' minds about what he means, Darwin includes this footnote: ‘In real stones, or in paste or soft coloured glass, many pieces of exquisite workmanship were produced by the antients. Basso-relievos of various sizes were made in coarse brown earth of one colour; but of the improved kind of two or more colours, and of a true porcelain texture, none were made by the ancients, nor attempted, I believe by the moderns, before those of Mr. Wedgwood's manufactory. (89)’ In fact, Wedgwood is mentioned in three of the four substantive footnotes in Section VI of Canto II, which also includes an interleaved engraving of two of Wedgwood's commemorative medallions. Darwin's puffery certainly afforded Wedgwood public exposure: The Botanic Garden went through several editions over the course of the Romantic period in London, Derby, Dublin, and New York; a French translation appeared in 1799, a Portugese in 1803, and a German translation was brought out in 1810.

In Darwin's long footnote that interprets the Vase's designs, Josiah Wedgwood himself—not Hamilton or any of Wedgwood's carefully selected Portland Vase endorsers—is positioned as the expert on the artifact. Contrary to positions taken by antiquarians or fine artists, Darwin finds the pinnacle of aesthetic perfection in neither in ancient classical artifacts nor in native fine art. It is extraordinary that Wedgwood could have accomplished such a feat, but in Darwin's poem, the manufactured craft object has more cultural credibility than the work of art. In a striking example of the Benjaminian formula, Wedgwood's reproductions not only disrupt the authority of the original work of art—they supplant it.

A painting by Benjamin West further demonstrates that Wedgwood's Portland Vase copies achieved consecration in the London art world. As they do in Darwin's poetry, Wedgwood's copies of the Portland Vase occupy a central place in West's painting. David Irwin goes so far as to suggest that it is "presumably Josiah Wedgwood's first copy" of the Vase that appears in the painting, which would make it a representation of the very copy he presented to Darwin (Neoclassicism 173). In 1787, West was commissioned to paint designs to be used as decorations on the drawing room ceiling of the Queen's Lodge at Windsor. The Royal family had chosen the site of Queen Anne's lodging for their new residence, and the Queen's Lodge was the primary Royal Residence until it was razed after the death of both George III and Charlotte (Loftie 38). West's ceiling designs were executed by a German decorator named G.L. Haas, who had invented a sort of sand-art technique "to which no name ha[d] yet been applied" at the time the ceilings were put up (Windsor 119). It involved gluing colored marble dust to canvas or board and apparently had "all the force and effect of the best oil painting" (Windsor 119). Haas later took out newspaper advertisements calling his "entire new-invented" technique "marmot-tinto," and he mounted an exhibit at the rooms at 19 Great-Pulteney Street on 14 February of 1791.

According to a contemporary guidebook, The Windsor Guide, "The Ceiling consists of several subjects. In the centre, in an oval, is genius reviving the arts; in the four corners, are agriculture, manufactory, commerce, and riches, depicted by emblematical figures in the different vocations, with the symbols of several sciences" (119). In 1787, when West received the commission for the ceiling designs, the Portland Vase copies were not yet been complete. It is impossible to know exactly what the designs looked like, but West either changed his sketch to include the Portland Vase copy, or he produced a second one after the fact.

Fig. 3 Benjamin West, British Manufactory; A Sketch. Image taken from the Wikimedia Commons, where it is presented under Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

West's oil-on-paper sketch related to Haas's ceiling design, which bears the longer name Etruria or Manufactory Giving Support to Industry; the sketch is known simply as British Manufactory; A Sketch or sometimes as Etruria. Suggestive of the designs on the Vase, the central vignette depicts two allegorical female figures draped and dressed in classical garb as well as two naked boys, one a cherub. The boys are handing up a Wedgwood copy as well as a rolled paper, presumably a plan or paper model, to the seated figure of Industry, who is busily at work on a jasperware vase. Behind her, Manufactory holds a wheat-colored drapery into which a ceramic platter is nestled. At Industry's feet, various earthenware plates and vases are piled. Behind her, other scenes taken from the British textile industry fill the oval frame.

Although the sketch included the Portland Vase, the ceiling probably did not, since the date of the sketch is well after the date of the ceiling (Helmut Von Effra and Allen Staley 412). The Windsor Guide reports that the ceiling was "affixed up" early in 1789, two years before the sketch is dated. That West changed his painting in the first place indicates the importance and status of the Portland Vase copies. The ceilings in the Queen's Lodge were left to Hass, a mere decorator who appears to have only exhibited once, in a rented room at Golden Square. West's sketch, by contrast, was exhibited in the consecrated space of Somerset House. It is striking that the relationship of West's original vis-à-vis Hass's decorative copy is so radically different from the Vase's status as an object copied by Wedgwood, a craftsman known for producing decorative arts. It is even possible that West changed the design to include the Portland Vase as a response to Haas's exhibition, which went up just a few months before the Royal Academy's annual exhibition. If true, it serves to highlight the way Reynolds's directives regarding painterly improvement on originals might have been deployed to maintain a hierarchy where fine art trumps decorative craftwork.

In any event, the sketch was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1791 under the title British Manufactory; A Sketch. Before 1791, Etruria might have occupied the central spot in the ceiling medallion because of a sort of pun: Wedgwood had renamed his creamware "Queen's Ware" in 1765 when George III named him "Potter to the Queen," so decorations for the so-called Queen's Lodge might well have put the Queen's Potter in the center of the design.

However, after 1791, Wedgwood's successful copies of the Portland Vase gave West a more specific reason to place Wedgwood front and center. The same year, West also exhibited British Commerce; A Sketch and indeed most of West's exhibited work in the years before and after 1791 suggest that he was producing allegorical designs celebrating British industry and trade (Graves 215). Taken as a whole, these sketches, designed to be reproduced on a large scale, are reminiscent of James Barry's designs for the Great Hall of the Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. West's British Manufactory, if it does not exactly reference, certainly trafficks in the same imagery as Barry's depiction of British commerce and manufacture in that series of paintings.

Barry's aim in those murals was to combat the "illiberal picture of British genius" offered by the great antiquarian J. J. Winckelmann and to unite the "Grecian style and character of design, with all those lesser accomplishments the Moderns have so happily achieved" (Society of Arts iii, iv). Although the paintings had been completed and placed in the Great Room in 1783, they were contemporary news. West was adapting Barry's visual celebration of the manufactures just as Barry was finishing up his prints and distributing them to subscribers.

The year 1791 saw first Haas's exhibition, then Barry's print, then West's sketch.

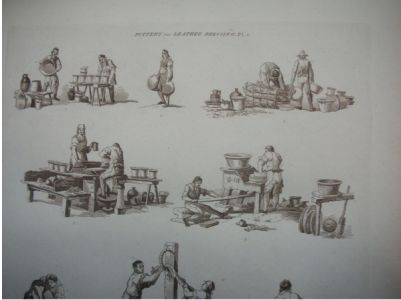

In May, Barry finished the engraving of his fourth Great Room frieze, Commerce or the Triumph of the Thames. The bottom right of Barry's picture is crowded with "Nereids," who carry "several articles of our manufactures and commerce of Manchester, Birmingham, &c." (Barry, Account 61). In Barry's description of the picture, he explains: ‘[I]f those Nereids appear more sportive than industrious, and others still more wanton than sportive, the Picture has more variety and I am sorry to add the greater resemblance to the truth; for it must be allowed that if through the means of an extensive commerce, we are furnished with incentives to ingenuity and industry, this ingenuity and industry is but too frequently found to be employed in the procuring and fabricating such commercial matters as are subversive to the very foundations of virtue and happiness. Our females...are totally shamefully, and cruelly neglected, in the appropriation of trades and employments; this is a source of infinite and most extensive mischief.... (Account 61-2)’ Barry quickly moves on from this bit of social commentary, claiming that he has treated a serious subject lightly (Account 62). In this context, it is interesting that in place of sportive, wanton nymphs, West offers the portrait of a somber female Industry. Wedgwood had been apprenticing girls since the 1770s, so that by the early 1790s a small but significant portion of Etruria's labor force was made up of women (McKendrick, “Discipline” 38). Records indicate that all together Wedgwood employed 278 men, women, and children in 1790, each with a specific, repetitive task (McKendrick, “Discipline” 33). Where Barry offers nudity, West provides a subject fully clothed in classical sandals, a sleeved peplos with a blue drapery, and a blue cecryphalus, or headband. Where Barry offers water nymphs and wanton sport, West presents Industry employed in decorating jasperware—the recently made most-famous example of English manufactory.

West's vignettes toward the back of the painting also offer utopic settings of industrial labor, wherein men, women and children appear perfectly at ease in their textile-making employments. However, Etruria and its most famous ware remain the central focus. The vase Industry is employed at painting has not been identified (von Effra and Staley 412). While West may not have had a specific Wedgwood vase in mind, the general shape of the vase, a kind of lidded amphora, does suggest a reference to Triumph of the Thames, which includes an ormolu amphora depicted in the bottom right of Barry's painting. Ormolu was a famous Birmingham production, pioneered by Mathew Boulton. Even as Barry proposed his Great Room paintings, the fashion for the Frenchified ormolu was waning, and Wedgwood's friend had moved on to minting coins (Uglow 416)—but in the post-1789 political climate vases like the one in Barry's painting were even less popular. The invention of jasperware and the success of the Wedgwood copies of the Portland Vase ensured that Josiah Wedgwood, with his prejudice against "French & Frippery" and wares "cover'd with ornament," gained supremacy over Matthew Boulton as the manufacturer most representative of dominant English taste.

Fig. 4 W. H. Pyne, Microcosm, or, a Picturesque Delineation of the Arts, Agriculture, Manufactures, second edition (London: W. H. Pyne, 1806), vol. 1, p. 5. Courtesy of Yale University Libraries. An example of contemporary labor vignettes.

The painting portrays Industry in medias res, before she has had a chance to take up the drawings or the Vase that the rather buff putto hands up to her. Industry and her allegorical support staff are depicted in classical garb, in keeping with Reynolds' dictate in Discourse X that modern dress is to be avoided "[h]owever agreeable it might be to the Antiquary's principles of equity and gratitude" (187). Allegory combines with achievement to elevate Wedgwood's works above the backgrounded labor vignettes, which are rendered in the more typical fashion. West's textile vignettes resemble those in books like Pyne's Microcosm, or, a Picturesque Delineation of the Arts, Agriculture, Manufactures &c., which certainly valorizes English manufactory but does so in a conventional visual genre. The Portland Vase copy is in the possession of the putti who sit on the factory floor at Industry's feet, at once celebrating the Vase’s classical origin at the same time it celebrates a contemporary achievement of mythic proportions. As with Barry's depiction of Commerce, the sea and the English cliffs are vaguely visible in the background, suggesting again that this English vase, worked by English hands and made from English earth, is worthy of reverence.

* * *

Throughout this paper I have been speaking of Wedgwood as if he were the sole designer and copier of the Portland Vase. Of course he was not. Just as West had a workshop filled with unnamed assistants—whom Blake, writing in the margins of Reynolds' Discourses, derisively called "journeymen"—so Wedgwood employed modelers and mold-makers who assisted him with the perfection of his jasperware copies. In our current moment, the arts find themselves under intense political, economic and institutional scrutiny. In the U.S., public arts funding came to the forefront of the 2012 presidential election when the Republican candidate said he would stop funding the National Endowment for the Arts. Under the current administration, funding continues a trend of decline.

At the same time, the economic value of "consecrated" art objects is in no danger. The international art market continues to increase as the wealthy invest and trade billions of dollars per year in commoditized objects of art and antiquity (Goodwin 1). The situation invites us to consider the attribution of value to art objects, how value is created, and who produces it. Wedgwood's ability to smooth the facets of factory production into a single end product bearing his name was new. However, I think his ability to leverage factory production at the same time that he brought together competing modes of institutional meaning was nothing short of remarkable. Highly liminal, these objects were produced in a factory; they were distributed, like prints or books, by subscription; they were displayed and catalogued like painting or sculpture. They were a financial failure wrapped in aesthetic success.

The Portland Vase and its Wedgwood copies undoubtedly served to prop up each other's aesthetic and economic value. Sir William's initial willingness to pay such an extravagant sum for the Barberini Vase and the subsequent buzz the Vase generated in London made Wedgwood's project a viable way to gain attention for his new invention. To this day, jasperware remains Wedgwood's best-known product. After the response to the Portland Vase copies, the factory could not resist making cheaper replicas to commercialize its aesthetic triumph. While Josiah's "original" copies were aesthetic achievements celebrated in the realm of high art, the factory went on to produce what Wolf Mankowitz described as "a moulded biscuit apology," onto which dark paint was applied to mimic the bas-relief appearance of jasperware (18). He goes on: ‘The particular characteristic of the 1839 copy is, however, the triumph of Victorian morality which it embodies. In it the figures, naked and austere in the original vase, are draped 'in the Greek manner', with a scrupulousness of which the Prince Consort himself would have approved. (18)’ Blake's fig-leaf-decked illustrations, which predate the Wedgwood company's Greek drapery by a half century, suggest that the urge to clean up the classical was Romantic rather than Victorian. Wedgwood's worry that copying the Vase would cost the enormous sum of £5000 in artists' labor was not far off—but Wedgwood's legacy of cheap nineteenth-century reproductions proved popular and more than made up for the expense of producing the first copies. It was only a matter of time before this triumph of technological innovation, marketing, and nationalism was subjected to three-dimensional mechanical reproduction. Since 1841, the factory has produced copies of various size and in various shades of blue. The consecration conferred upon the first copies by Reynolds, Hamilton, Darwin, and West made subsequent copies economically inevitable. As Wedgwood had imagined in his June 1786 letter to Hamilton, the Vase could indeed be "copied to suit the tastes, the wants & purses of different purchasers." Today, it will cost the average citizen a quick trip to ebay and around forty dollars to obtain a pale blue, genital-free Portland-Vase Christmas ornament; but patrons of the British Museum gift shop can purchase made-to-order Wedgwood factory reproductions of the Portland Vase for the exact sum of £5000.