In the spring of 2011, I taught a first-year writing seminar focused on fictional and non-fictional representations of the internet and digital culture.

As a devoted Romanticist, I envisioned such an opportunity as a chance to step outside my usual nineteenth-century base and see what effects the time spent in unfamiliar terrain might produce. My goal was to help students approach critically various aspects of technological life, and, in so doing, encourage them to reflect on the relation between college writing and the twenty-first-century media landscape. The connection between my initial conception of the course and Romanticism was tangential at most. I titled the course “Imagining the Internet” because I wanted students to see digital culture from a shifted intellectual perspective, specifically through the logic of defamiliarization that imagination enables. In particular I wanted to counter the reigning digital rhetoric, one which privileges immateriality as if it were actually the ontological condition of computing. From its beginnings cyberculture has represented the digital realm as one free from materiality, as in the emblematic early example of the hackers in William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) who long to escape into cyberspace and away from their bodies, which they derisively term “meat.” That immaterial ideology persists in our contemporary practices like cloud computing and syncing between devices, both of which give the impression that the data accessed has no fixed material basis, but merely exists as eternally mutable zeroes and ones. As such, “imagination” may have seemed an odd choice, given that it tends to be understood as the mental faculty capable of transporting us out of embodied experience, in a manner akin to what cyberspace purportedly enables. Instead, I wanted students to discover some of the complex material exchanges that make possible digital culture’s aura of immateriality, and to do so by imagining the materiality that so easily eludes our grasp of the digital. Although I began the course assuming that it would take me into new territory, I quickly found myself in a space eerily familiar to me as a Romanticist, a space where imagination, ideology and materiality exist in fraught relation to one another. In this essay I recount that experience as a way to reflect on the overlapping domains of teaching and research, new and old media, and the frameworks that help us place their iterative connections.

In what follows, then, I demonstrate how I presented my students with the digital rhetoric of immateriality, how we attempted to resist that rhetoric with the aid of digital tools, and how that process illuminated what it means to imaginatively embody Romantic texts, an illumination that additionally cast light back on new media. Romantic theories of imagination offered a conceptual framework for students to intellectually and creatively rematerialize the seemingly immaterial nature of digital objects. As Lori Emerson argues concerning interface design trends in contemporary computing, new media interfaces are now “steadily making their way toward invisibility, imperceptibility, and inoperability” (1), characteristics which become equated rhetorically with “naturalness” and the devices’ seemingly “magical” properties (4–19). When dealing with technologies of such complexity, when, as Percy Shelley claims, “our calculations have outrun conception,” the imagination can effectively make strange the perceived naturalness of computing and bring materiality back into view.

Now more than five years after the teaching experience I relate in this article, I have taught Romanticism several more times, in different contexts (as part of a survey, in seminar form devoted wholly to Romanticism, as part of a genre-based course) and to different audiences (undergraduate English majors and non-majors, MA and PhD students), and as a result I am more confident in my conviction that when we teach Romanticism, we teach a form of media studies. Imagining a medium (old or new) just is doing Romanticism. In that sense, the habits of mind and practice outlined here signify a pedagogy of Romanticism as much as one for Romanticism.

I. “There is no matter here”: The Illusions of Medial Ideology

The intellectual kernel that led me to develop the course, and which began to solidify in my mind the productive connections between Romanticism and new media studies, was Matthew Kirschenbaum’s identification of a “medial ideology” pervading the study of electronic media. Acknowledging his debt to Jerome McGann’s notion of “Romantic ideology,” Kirschenbaum defines his related ideology as “one that substitutes popular representations of a medium […] for a more comprehensive treatment of the material particulars of a given technology” (36).

Kirschenbaum demonstrates how the representations of digital culture portray new media as divorced from the material aspects of its existence—we treat zeroes and ones as if they were merely abstractions, not as metaphors to signify particular material processes. To establish some of the course’s foundational assumptions about new media, then, I introduced my students to a variety of “popular representations of [the] medium.” We aimed to read these texts through a conventional humanities practice: ideology critique. The specific aspect of digital ideology we examined was the assumption that bodies do not matter, and that material concerns disappear in the purely disembodied flow of data. One can witness that assumption’s most extreme form in the desire to translate the human brain into binary code and thereby achieve digital immortality (by now a common science fiction trope as well as an actual goal of many technological enthusiasts), but it also persists in the banal versions one encounters regularly in the practice of everyday digital life. The first example discussed here, and one of the first texts I presented to my students, falls squarely in the former category: John Perry Barlow’s “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” first published in February 1996 through the Electronic Frontier Foundation, an internet advocacy group co-founded by Barlow. In what became a widely copied and disseminated document of the early Web, Barlow addresses the “Governments of the Industrial World,” the “weary giants of flesh and steel” who have no sway over “the new home of Mind,” rhetorical figures which pose industry as the evil cyborg enemies of the pure spirit of humanity. Cyberspace is posed as “an act of nature […] [which] grows itself through our collective actions,” and that such growth “consists of transactions, relationships, and thought itself, arrayed like a standing wave in the web of our communications.” With freedom from the trappings of industry, politics, capitalism and other material concerns, Barlow insists of cyberspace, “there is no matter here.” The social reorganization promised by cyberspace extends to individual subjectivity as well, with a similar stripping away of matter. Barlow claims that “our identities have no bodies,” and that, like the discrete packets of bits that zoom across the globe from one computer to another, they are endlessly mutable and mobile. These bodiless identities, without the limitations of material existence inhabit a world of pure imagination: “whatever the human mind may create can be reproduced and distributed infinitely at no cost.” Or, we might say, channeling Gene Wilder’s Willy Wonka, “If you want to view paradise, simply look around and view it. Anything you want to, do it. Want to change the world, there’s nothing to it.”

So says another representative example that my students and I analyzed: an AT&T advertisement from 2010 which uses “Pure Imagination” as its backing music. The ad co-opts the rhetoric of early techno-utopian manifestos like Barlow’s, but it drastically changes the kind of “freedom” on offer. Freedom in the ad means life in a corporate world with the promise of escape through the internet, even as the network itself becomes more corporatized and centrally controlled through seemingly ubiquitous points of access and handy “tethered devices.”

The ad shows various young urbanites navigating through a post-industrial world, still one of flesh and steel, and yet they seem unaware of the magical world that pulses around them (like a wireless network), here pictured in the form of childlike drawings brought to life amidst the cityscape. Toward the commercial’s end, the drawings all collapse, suggesting the end of imagination precisely at the moment that the objects become fully material (a train crashes into a wall; a three-eyed monster drapes over the side of a bridge; a giant robot falls to the ground, along with his attendant cloud shapes). After the figures disappear, the ad cuts to an isolated man sitting on a bench perched on a concrete overlook, his head downcast, his shirt unbuttoned and tie loosened, his briefcase, coffee and lunch next to him—all helpful details suggesting his post-industrial ennui, presumably the cause of the imaginary figures’ departures. But suddenly, the man remembers his smartphone, and its unearthly glow lights up his now smiling face, as one of the imagined figures return to the scene. Once again he lives in a world of pure imagination.

In addition to introducing the ideology of cyberspace as a disembodied, immaterial realm free from politics, class, and matter itself, I used these two texts to reflect on the way we access and interpret such materials. YouTube, the site on which we watched the ad, is a vastly useful collection of visual materials, but not a transparent one. Our class discussed, for example, YouTube’s (then current, now defunct) motto, “Broadcast yourself,”

as an intentional alignment with the history of amateur broadcasting in the early twentieth century, which has repeatedly followed the pattern of innovation, amateur development, and corporate appropriation described in The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires (2010) by Tim Wu. With the AT&T ad, the self that is broadcasted is named “attoffer,” and when you click on “his” personal website, it unsurprisingly directs you to offers for a subscription to AT&T’s various network services. What begins as an open service, a place where anyone can post videos for free without limitations on access and ownership, becomes increasingly closed, regulated and centrally controlled. While peddling immaterial ideology to the extent that the “self” is the message being broadcast, as Barlow hoped identities without bodies might do, YouTube suggests, through its specific medial transactions, a contradictory set of ideas about what pure imagination through a network might entail. Here the freedom of cyberspace comes at a cost, one that “attoffer” will happily specify, even as its parent company’s rhetoric obscures the material interactions through which the network functions.

After introducing this particular awareness of digital materiality, I hoped to help students to see immaterial ideology as ideology. Discussing texts like Barlow’s “Declaration” and the AT&T advertisement certainly began that process, but those methods were firmly rooted in an old method: ideologically attuned close reading. I wanted also to use digital tools to demonstrate the ways in which our experience of digital culture comes back to materiality. Text analysis software, for instance, offers a particularly striking way to reflect on textual materiality and to imagine what it might mean to reintroduce material specificity to digital objects. By demonstrating a text’s mutability as it moves from one material medium to another, the complexities of textual signification become newly visible.

When the class read Rudy Rucker’s classic cyberpunk novel Software (1982), we put the novel’s entire text into a web-based program called Voyant, which analyzes the number of occurrences of distinct words, and allows the manipulation of them in various ways. One can view a word cloud (the larger words representing visually their higher relative frequency), chart one word against another, track a word’s appearance at different times throughout the book, and otherwise manipulate the textual “corpus” as a dataset. With Software, for example, one can track “software” and “hardware,” the two terms around which the novel dramatizes its main concerns regarding identity and embodiment. Early on a character opines that “the soul is the software” (62). Cobb Anderson, the inventor of the intelligent robots called “boppers,” gets rewarded by his creatures, who translate his soul into new “hardware,” a robot body that looks exactly like his human one, and which negates the pesky problem of mortality. By isolating the two words, one can view them in context across all their instances in the novel in different visual and linguistic representations.

Of course, one can accomplish a similar task, but more slowly, using traditional reading methods. The usefulness of a digital tool like this one rests on the altered presentation of information that we might alternatively access through print. I foregrounded this particular realization for my students by focusing on the manipulation of the text required to produce such a representation, a process that reinforces the material specificity of texts, and the variations that occur between digital and print. Rucker published, in 2010, the entire Ware Tetralogy (Software and its three follow-ups) in a single-volume print edition, which my students purchased for use in the course. Students could alternatively read the novel in digital form, which Rucker simultaneously published for free as a PDF made available through his website and distributed under a Creative Commons license. Even with most of the remediation already done for us, the process of transporting the digital text into another software environment allowed us to reflect on how we might understand “text” in relation to the novel’s interest in software and hardware. The novel’s linguistic data became akin to code that we could run on the different software and hardware configurations of a print book, a PDF reader, or a web-based text analysis program.

One particular problem, however, demonstrated how the process of textual migration itself, like the transmission of Cobb’s “software” (the data that makes up his “soul”) into new “hardware” (a fresh robot body), reoriented the nature of the novel’s print and digital materialities. When copying and pasting the text from the PDF, the running header, reading “Rudy Rucker” and “The Ware Tetralogy: Software” respectively on the verso and recto (terms complicated by the typical single-page display of PDFs), becomes part of the “corpus” analyzed by Voyant. When tracking the instances of the word “software,” the numbers get significantly skewed (since it appears seventy-three times in the header). The result of witnessing this material negotiation of a print-based text simultaneously published in digital format and then transported into another instantiation was that my students had to consider the text “as a laced network of linguistic and bibliographic codes” (Textual Condition 13). Do we count those seventy-three instances of “software” that occur in the header? Or rather, how do we count them and account for their meaning? Such questions become relevant when manipulating the text with an awareness of the particular transactions that make such manipulation possible. Like the novel itself, which skeptically regards the transmission of one’s “soul” via software implemented in new “hardware,” our treatment of the digital text in relation to its print forms helped us see the processes of transmission not as transparent, but rather as contingent upon specific material factors.

In addition to analyzing print-based materials with the aid of digital tools, the class also examined born-digital texts to see further the obscuring effects of immaterial digital ideology. Students took a particular shine to a project by Leonardo Solaas, a programmer and new media artist who created Google Variations, a net-art installation that re-presents Google in altered states. Most of the variations present a functional Google homepage with only slight tweaks. “The Google Pond,” for example, creates a visual ripple effect when moving the cursor over the page. Similarly, “Paint it Google” transforms the cursor into a paint tool, and the page into a color palette and canvas. Others have a more programmatic purpose and a lesser degree of functionality. “Google is God” displays six separate pages, designed to look like individual search results from Google, all of which present quotations regarding the correspondence between Google and divine power. The final result, however, gestures outside of Solaas’s pre-programmed response, and opens an actual Google results page for the query, “google is god.” The movement from “net art” to genuine web page occurs without signal and as such works toward Solaas’s goal of destabilizing and denaturalizing what has become such a dominant feature of internet use. The final variation, titled “The Future,” reinforces the contingency of Google, and of all such digital objects. It displays a typical “HTTP 404,” or “Page Not Found,” error message, a standard code to indicate when communication with the server is intact, but the requested page could not be found. The title of the requested page in this case is “some/day/google/will/not/be/there/.” The implication, of course, is that Google’s server has no such page because Google does not anticipate such an eventuality. The “missing” page nonetheless speaks by virtue of its absence. Solaas’s presentation reminds us that Google will not exist for all eternity (an obvious truth), but furthermore that the nature of its existence is contingent upon the particularities of our material interfaces and programming and always experienced in relation to the larger culture of computing.

The denaturalizing of digital objects performed by a work like Google Variations enabled students to adopt a similar perspective in their own productions. All students were required to write for our course blog, a forum in which they could reflect on and treat critically (and playfully

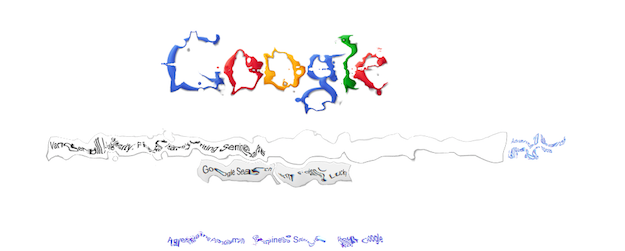

) the particular communicative modes enabled by the blog form. As is typical of the form, students regularly used media in their posts, linked outside the blog, referenced other peers’ posts, and perhaps most useful for the course’s writing instruction goals, self-consciously adopted a tone more informal than that employed in their academic papers. We specifically discussed that difference in our conversations about academic writing in multiple class sessions devoted to peer review. I also asked students to contemplate the particularities of expression enabled by their word processing software when writing their academic essays. For their second paper, I assigned students a relatively conventional comparison paper (analyzing texts from two different media), but with the additional stipulation that they manipulate their medium with something in addition to text. For most students this meant embedding images or video in their essays, but even this simple task helped them reflect on the content of their papers: rematerializing and denaturalizing digital objects. For example, one student writing about William Gibson’s Agrippa (1992) and Solaas’s Google Variations argues through an analysis of the two works “whether a user is forced to submit to a medium or is granted options, the mechanism through which one receives information dictates the interpretation of that information.” She writes that Google Variations “reminds users of their role on a search engine since every movement creates a new effect,” which in turn helps to erase the influence of Google itself: namely, that because of Google’s ubiquity, “the user forgets the mechanism, allowing the mechanism to have an influence without the user’s awareness.” By embedding in her essay screenshots of her manipulation of Google Variations, the student reinforced her argument visually and methodologically (Figure 1). In effect, her image of “Paint it Google” represents the kind of awareness of “the mechanism” she describes in the paper. Not only has she altered the page by using the cursor to deform Google’s logo, she has also typed in the search box, obscured but still legible, “Vanderbilt University First Year Writing Seminars,” of which our course was one. This moment of textual and visual play gets “captured” by her computer’s screen capture software, and then redeployed in its modified form by conscious manipulation of the software that enables her to compose her essay. The essay itself, a product of the course being queried in her altered Google, becomes another digital object subject to the conscious manipulation of media she describes in the paper’s argument and analysis.

Fig. 1 An image from a student’s paper. She created the image by taking a screenshot of her manipulation of Google Variations’ “Paint it Google” mod.

Entering into this assignment, and into the course more generally, I assumed that it would be valuable to adopt digital methods and tools since the course content was focused on new media. I came to realize more strikingly what I had only intuited to be true before: that such tools are valuable for the kinds of insight they produce, not simply because they exist and so must be worth adopting. Objects like Voyant’s text analysis software, Wordpress’s blog platform, and even Microsoft Word as a basic—and, some would say, poor—multi-media compositional tool all encouraged students to see their own practices with digital technologies in relation to the intellectual stance we were taking toward computational practices more broadly. Our discussions of digital culture’s ideology of disembodiment and immateriality helped to reorient the way students looked at digital objects, including their own work. The tools we used in producing and reflecting on that reorientation continued the process of rematerializing the digital that we began by close reading. Of course, such tools do not inherently encourage an awareness of materiality—they can just as readily obscure computational processes. Tools do not function transparently, and most of us lack the technological expertise required to conceive fully of their mechanisms. However, using the tools can produce understanding of a different sort. The re-presentation of digital objects in altered forms allows for and encourages imaginative knowledge of the relation between virtual and material. Romantic notions of imagination prove particularly useful to support this stance precisely because such theories of imagination insist on the material forms that communicate the seemingly immaterial nature of imaginative experience.

II. Imagining Matter

To connect more directly digital ideology with Romantic imagination, let me offer one further example of that ideology’s emphasis on immateriality. “The cloud” has become a ubiquitous term in the past few years, thanks in no small part to Apple’s honorific christening of its cloud-based service with the obligatory prefixed “i.” Essentially, cloud computing refers to the practice of remotely storing data which can be accessed through a network, as opposed to storing data on a local hard disk (like the one in a personal computer). Apple announced their iCloud service at the Apple Worldwide Developers Conference in June 2011.

In the keynote address, Steve Jobs playfully remarked, “Some people think the cloud is just a hard disk in the sky […] We think it’s way more than that, and we call it iCloud.” What distinguished iCloud from other cloud services (such as Dropbox), is that iCloud promised automatically to integrate storage across multiple devices and within various applications without the user having to make such changes actively (in Dropbox, for example, the user stores data through the same logic of files and folders that governs storage on a local disk). iCloud, in the words of Jobs at the keynote, “just works.” The implications for this development meant that computational devices would no longer function primarily as storage receptacles, but rather as access portals to data stored elsewhere and managed largely by someone (or something) else. As Nick Bilton put it on the New York Times’ Bits blog in response to Jobs’s keynote, with iCloud, “Apple is reiterating the irrelevance of the personal computer.” Furthermore, it is forwarding that irrelevance through immaterial rhetoric relating to digital data storage and retrieval.

As Apple’s iCloud promotional materials explain, photos, music, or other documents created or edited on one device get stored in the cloud, which then automatically “pushes” the objects to all other devices. The “push” is visually represented by Star Trek-esque blue rays, which connect the moment of inscription on one device, subsequent storage in the cloud, and the journey back to other devices. This is digital data unmediated by the old metaphors of computing, the now naturalized files, folders, and desktops—those pesky reminders that even digital objects are material (at both the “forensic” and “formal” levels, in Kirschenbaum’s schema).

Yet even as the cloud metaphor dematerializes the physical, political, and economic exigencies that make possible remote storage and retrieval (“it just works”), the sleek metallic image of the iCloud logo reminds us that Apple’s cloud is open only to those who possess sleek metallic devices to match.

The carefully machined aluminum comforts because it connects us to loved ones through near magical transactions that elide material considerations—like the mining of bauxite needed to produce the aluminum that makes the device possible.

The cloud, then, is a medium that erases its presence, even if we think of ontology in terms of “commands, addresses and data,” as Friedrich Kittler argues we should when concerned with technical media. Doing so eliminates, or at least deemphasizes, the material negotiations behind the transactions that occur between processes, transmission and storage. With cloud computing, for instance, storage still occurs on a physical server somewhere, typically in large data centers like the one Apple is currently building outside of Reno, Nevada or the recently completed one in Prineville, Oregon, which it built to help accommodate the storage demands of iCloud when it debuted in late 2011. The Oregon storage center neighbors a similar facility owned by Facebook, another company that stores massive amounts of data. Both companies benefit from a recent property tax law passed by the Oregon state legislature (SB 1532), which Senator Mark Haas claims “will allow the state to stay competitive while attracting additional high tech companies to Oregon” (“Oregon Senate OKs Facebook Tax Fix”). Similarly, the Apple data center in Nevada will benefit from 88 million dollars in tax exemptions (Harkinson). The representations of cloud computing, however—the image of little blue rays connecting your device to the cloud, the logo of the metallic cloud itself—obscure the very material, economic and political interactions which become reinscribed as processes that occur “Everywhere. Automatically… Just like that” (“Apple—iCloud”).

I focus on the “cloud” here since it is an image invoked frequently in the Romantic period, thanks largely to Luke Howard’s 1803 Essay on the Modifications of Clouds, the basis of our modern cloud classification system. Goethe wrote enthusiastically about Howard’s system, claiming that it “bestow[s] form on the formless and a system of ordered change on the boundless” (qtd. in Slater 120). In a poem praising Howard, Goethe writes that “He grips what cannot be held, cannot be reached, / He is the first to hold it fast” (qtd. in Badt 12). Howard, in other words, connects the material and immaterial realms, and through his systemic model encourages further imaginative insight through aesthetic representation. As John R. Williams writes in his biography of Goethe, the poet saw Howard’s work as demonstrative proof that “the disparate, the inchoate, the ephemeral and the apparently unstable can be grasped, intuited, and shaped by the ‘living gifts’ of the creative imagination” (119). Howard’s accomplishment, according to Goethe, was providing a systematic model through which imaginative thinking could operate on and reveal the matter of clouds. Similar to how digital tools helped my students reorient their understanding of what constitutes digital materiality, Howard’s scientific system enabled the further imaginative understanding of natural phenomena.

The cloud, which in the Romantic period provides evidence of the imagination’s capacity to act on external matter, gets translated back into a figure of immaterial communication in the rhetoric of digital technology. This turn is unsurprising given the long history of equating Romanticism more largely, and Romantic imagination in particular, with escape from social and material history. Recent scholars on imagination, however, have focused on the way that it operates in relation to materiality. Alexander Schlutz, for example, ascribes imagination’s problematic status in the history of philosophy to its “peculiarly liminal position,” poised between “mind and body, self and world, the ideal and the real” (5). Imagination challenges Enlightenment accounts of subjectivity precisely because of its connection to the senses and the body, and its mediation of the external world to internal understanding. In short, imagination exposes the illusion of “the mind’s freedom and autonomy from the vicissitudes of its physical embodiment” (4). Richard Sha similarly rematerializes imagination by situating it in the context of Romantic-era medical discourse. Sha notes that in Romanticist scholarship, imagination has been long maligned as a tool of ideology, the escapist faculty “on the side of the immateriality of consciousness” (198-9). His argument, however, suggests that imagination held such appeal to the Romantics because it was understood physiologically. Even though medical discourse warned of the imagination’s ability to disease the mind and body, that recognition paradoxically “made unassailable the imagination’s ability to transform matter” (199).

What the course’s attention to imagination in new media discourse revealed was that another way to rematerialize the imagination is to conceive of it as a medium.

Shelley’s poem “The Cloud,” for example, uses it as an image, like Apple’s, of storage and transmission. Similar to his “balloon laden with knowledge,” and to the west wind carrying “dead thoughts over the universe” (“Ode to the West Wind,” 63), Shelley’s cloud is a channel through which information may travel.

She carries “fresh showers for the thirsting flowers;” she “bears light shade for the leaves when laid / In their noon-day dreams” (“The Cloud,” 1, 3-4). Like the iCloud, she has a tenuous materiality, and can “pass through the pores, of the oceans and shores” (75). At the same time, she is “daughter of Earth and Water, / And nursling of the Sky,” and so unites heaven and earth, mind and body (73-4). Like imagination, she mediates between matter and spirit, functioning as a channel through which historical actors can “hold an unremitting interchange / With the clear universe of things around” (“Mont Blanc,” 39-40). In “A Defence of Poetry,” the job of imagination is to manage the “materials of external life” (531), which have been multiplying through developments in science and technology, like the classification of clouds, to the extent that “our calculations have outrun conception; we have eaten more than we can digest” (530). Instead of enabling escape from matter, imagination puts the body and spirit into proper relation to one another. Without the poetic, imaginative power, the “body […] become[s] too unwieldy for that which animates it” (531). For Shelley, language is an originary product of imagination, but the “materials, instruments and conditions of art” give us only secondary access, such that unmediated language is a “mirror which reflects” while expression through physical forms is “as a cloud which enfeebles.” Both unmediated conception and mediated expression, however, whether mirror or cloud, cast rays of light which are “the mediums of communication” (513). Shelley attempts to idealize language, poetry, and imagination apart from matter but keeps returning to the necessity for “portals of expression from the caverns of the spirit” (532). In other words, imagination functions only by manipulating the materials of existence, the dead leaves of thought, the enfeebling clouds that render our calculations conceivable, and of course the texts that come down to us. Even if they fail to some extent, the mediated forms of imagination provide the best and only way to communicate the experience of unmediated imaginative experience. Imagination is such a treasured mode of thought precisely because of its ability to link the realms of mind and matter, spirit and body, innocence and experience, and furthermore to communicate those relations through materialized forms of expression. Perhaps this view of the cloud, and of electronic media more broadly, as a material negotiation between processes, transmission and data storage helps “thicken the medium” (McGann Textual Condition 14) even as it represents itself as the absence of mediation.

John Keats’s thoughts on imagination posit it as a similarly mediating force, bridging the mind and body. A key word in his thinking is “ethereal,” which seemingly refers to immateriality but nonetheless often registers in the material realm.

Take, for instance, his statement of poetic purpose at the beginning of his tour of northern England and Scotland in the summer of 1818: “I shall learn poetry here and shall henceforth write more than ever, for the abstract endeavour of being able to add a mite to that mass of beauty which is harvested from these grand materials, by the finest spirits, and put into etherial existence for the relish of one’s fellows” (I, 301).

The work of poetry involves material processes like harvesting and increasing beauty’s “mass,” while also transforming that material into new forms that hover between mind and matter—the “etherial” things are “relished” in the mind and body. In a playful letter to Benjamin Bailey from a few months earlier, Keats divides “Ethereal things” into three divisions: “Things real—things semireal—and no things” (I, 242-3). Those of the second category, “Love, the Clouds &c […] require a greeting of the Spirit to make them wholly exist.” The sonnet he produces as an elaboration on his ideas represents “the mind of Man” following the progression of seasons, beginning in “lusty spring when fancy clear / Takes in all beauty with an easy span.” Like Coleridge’s distinction between secondary imagination and fancy, Keats puts the next stage of thinking into the creative realm: in summer the mind “chews the honied cud of fair spring thoughts, / Till, in his Soul dissolv’d they come to be / Part of himself” (I, 243). The more active role of imagination is to transform the materials of the external world into a part of the self, understood through the material processes of ingestion and digestion. As Coleridge elaborates his system, quoting from the Elizabethan poet, John Davies, “As we our food into our nature change,” so too does the imagination act upon physical materials (496).

The imagination, in these reflections, does not transport identity outside the body but rather reinstantiates it in a newly altered but still embodied presence. Keats’s anecdote about embodying a sparrow is instructive here: “if a Sparrow come before my Window I take part in its existince and pick about the Gravel.” He means this as an illustration of his constant focus on the present—“nothing startles me beyond the Moment”—but it comes in a letter reflecting on imagination (I, 186). In this letter he makes his well-known comparison of imagination to “Adam’s dream—he awoke and found it truth” (I, 185). Keats also suggests that imagination is the basis for what an afterlife might resemble, or “the redigestion of our most ethereal Musings on Earth” (I, 186). The ability to occupy another body, like the sparrow’s, is a product of imagination as a meeting of spirit and body. The poet fulfills this “negative capability,” of “being in uncertainties” (I, 193) of “continually […] filling some other Body” (I, 387). In this sense we can conceive of Keats’s embodied identity as virtual, as produced through an imaginative relation between experience, thought and sensation. Such virtuality does not erase materiality, but rather revises one’s felt experience of embodiment.

The imagination, then, as formulated by Shelley and Keats, offers a renewed conception of what it means to inhabit a body in a materially-bound existence. This insight, I realized from my experience teaching about digital culture, could apply as well to how we study new media and to how we ask our students to understand digital tools through classroom practice and critical orientation. Both the concepts and the practices renew our sense of materially embodied experience in the world, which is what digital tools should do for our students—help them come to know the ways in which they live as historical bodies in and of the world. To do so we brought imagination—rendered immaterial in new media discourse—back to matter.

III. The Matter of Texts, Digital and Otherwise

When we rematerialize imagination through media, we necessarily reimagine texts. In one of his long journal letters to his brother George and sister-in-law Georgiana, Keats writes: ‘our friends say I have altered completely—am not the same person—perhaps in this letter I am for in a letter one takes up one’s existence from the time we last met—I dare say you have altered also—evey man does—Our bodies every seven years are completely fresh-materiald […] We are like the relict garments of a Saint: the same and not the same: for the careful Monks patch it and patch it: till there’s not a thread of the original garment left. (II, 208)’ The letter becomes a textual body that Keats fills with his imaginatively produced, virtual identity. And like the physical body continually “fresh-materiald,” or like the holy patchwork garment, the reimagined textual self undergoes transformation through the negotiation of imagination and matter. This recognition disturbs as well as excites. Keats reflects that “’T is an uneasy thought that in seven years the same hands cannot greet each other again” (II, 209), a thought which can potentially threaten the stability of identity. Imagination, however, enables texts (or bodies) to communicate effectively: “All this may be obviated by a willful and dramatic exercise of our Minds towards each other” (II, 209). The imaginative “exercise” of mind relocates embodied identity in the shifting matter of existence: alternatively, in Keats’s formulation, bodies and texts across time and space.

In focusing on the imaginary processes Keats links with forms of mediation, I share Yohei Igarashi’s recent contention that “communicative mediation constitutes a significant, although still largely unremarked, concern of Keats’s poetry and letters” (173). And like Igarashi and several other Romanticists writing in the last decade or so, I also conceive of the Romantic era more broadly as crucially shaped and defined by its privileged place in “the history of mediation.”

Jerome McGann and Alan Liu have, in different ways, argued for the capacity of new media to help us “imagine what we know” about old media, as McGann puts it, borrowing from Shelley.

But we’ve also seen an increasing number of scholars attempt to recover “the conceptual breadth of early discussions of media,” as James Brooke-Smith describes some of the insights articulated by Kevis Goodman in Georgic Modernity and British Romanticism.

Celeste Langan and Maureen McLane locate in Romantic poetry such a sophisticated sensitivity to issues of mediation that they posit, “Romantic poetry might even serve as a synonym for what we mean by multimedia” (239). My experience of teaching new media suggested to me a similar reversal of the usual linear narratives of media history. As Siegfried Zielinski poses the issue in calling for a media archaeological method: “do not seek the old in the new, but find something new in the old” (3). To do so requires an openness to being in uncertainty about Romanticism and the history of mediation. My ultimate contention, then, is that the materiality of the Romantic imagination is that of a medium. Mediums imagine for us, and we imagine through them. Imagination communicates between mind and body, matter and spirit, and by doing so makes possible the affects of aesthetic experience that come through material forms like texts. Writing about Keats’s “La Belle Dame,” McGann claims that “Romantic imagination emerges with the birth of an historical sense, which places the poet, and then the reader, at a critical distance from the poem’s materials” (Romantic Ideology 79). By “materials” McGann means the ballad and romance traditions, mythological figures, and the particular perspective through which Keats revives them. I would add that the imagination emerges with a self-consciousness about the poem’s physical materials, its production, and the distance between conception, expression and reception. In imagining what a medium can do, Romantic writers mine the ontology of media, always aware in the end of the ineluctable limitations of communication. As Alexander Galloway, Eugene Thacker, and McKenzie Wark argue in their collaborative volume: “Every communication evokes a possible excommunication that would instantly annul it. Every communication harbors the dim awareness of an excommunication that is prior to it, that conditions it and makes it all the more natural” (10). For the Romantic writers, mediums function when they fail, as with Keats’s claim that in our embodied and textual forms, “We are like the relict garments of a Saint: the same and not the same” or Shelley's recognition that we necessarily rely on imperfect “portals of expression from the caverns of the spirit.” In an era of perpetual triumphalism for each new and improved shiny happy media machine, perhaps we need now to look to broken forms, dysfunctional devices, and the faultures of other decrepit things.

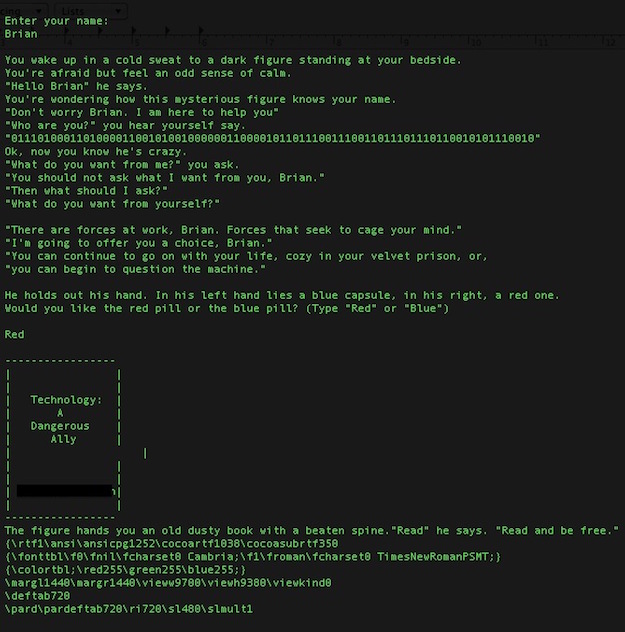

I’d like to conclude by sharing a final example of student work from the course, since this student demonstrated the kind of knowing, critical playfulness toward the history of mediation that can help to rematerialize our relation to the digital, and especially since he embraced the breaking points of media. I’ll call this student “Neo” since he was writing about The Matrix (1999) and showed some programming skill. As described above, the assignment asked students to write a comparison paper about two texts from different media, and to use multiple media forms in their papers. To meet the latter criteria, many students creatively employed video and image in their papers (as with the screenshots of Google Variations mentioned earlier). For his multimedia component, Neo wrote a computer program. He gave me instructions on how to compile the Java program on my computer, and when I eventually managed it, it produced the following. (Figure 2).

Fig. 2 A screenshot showing the narrative produced by my student’s Java program.

The program asks you to enter your name, and once you do, it produces this narrative, inspired by and loosely adapted from The Matrix. A mysterious figure offers you truth in the form of a red pill. Prompted again to type “red” of “blue,” the input “red” outputs the rudimentary image of a book, with Neo’s essay title on it. The final line of the narrative reads: “The figure hands you an old dusty book with a beaten spine. ‘Read,’ he says. ‘Read and be free.’” The program that has produced the narrative, also produces the content of the essay, the “book” that will lead to freedom. After the introductory narrative, the program outputs the entire essay text. (Figure 3).

Fig. 3 The end of the introductory narrative and the beginning of the student’s essay. In between are the formatting details from Word that the particular software environment cannot interpret.

With this creative representation, Neo recognized his remediated paper as part of a history of mediation. The green text on black screen recalls an earlier era in computing, inspired by The Matrix’s popularization of the green on black image, while the textual interface gestures toward text adventure games, or interactive fiction. The presence of his paper in the metafiction as “an old dusty book,” both suggests that old media continue to hold value (precisely because of their anachronism), and belies the separation of old and new (since the old book is being delivered simultaneously as Word document and script in a Java program). But even more significantly, as Neo wrote in his instructions to me, “the original manifestation of the piece [the essay as a word document with all its formatting details] is limited by the ASCII interpretation by the specific computer.” As a result, before the essay text is a long string of unreadable characters (for instance, “{\rtf1\ansi\ansicpg1252\cocoartf1038\cocoasubrtf350…”). These characters fail to signify to (most) human eyes, but also to the Terminal program, which cannot render the formatting instructions from Word into sensible form, and instead leaves them as inert code. Neo’s insight reminds us that all electronic media are not one, that we continue to experience new media through engagements with the old, and that the material specificities of such engagements can be rendered visible through informed representation. The mediated, mediating Romantic imagination, which appears so frequently disembodied in the evolution of digital discourse, can help us see the materials that make up that history.