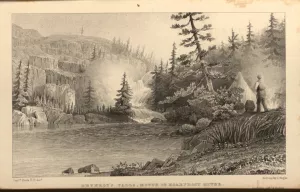

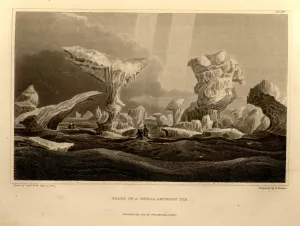

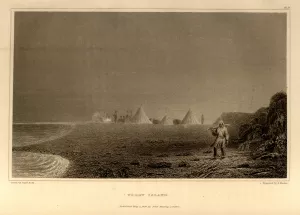

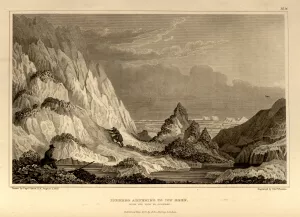

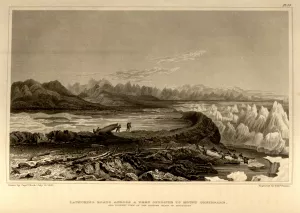

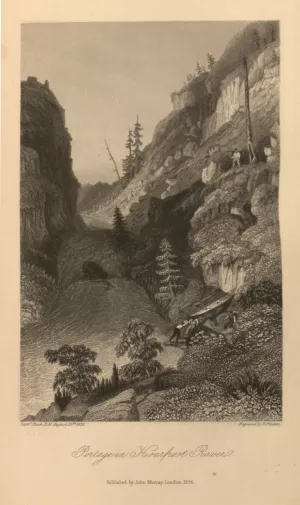

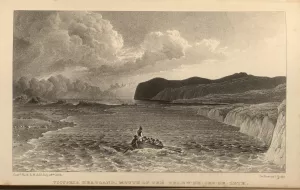

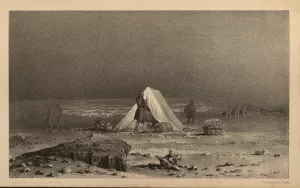

The artwork of Sir George Back, Royal Navy explorer of the Canadian Arctic, invites our reexamination of the paradigms of Romantic visual culture via its depiction of the “otherness” that the Arctic represented to the British during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as well as the difficulty of physically navigating that landscape. A compelling combination of the picturesque, sublime and “true-to-nature”—a combination sometimes found in just one image—Back’s artwork is almost equally aesthetically and scientifically driven, and as such walks a peculiar line that evades merely imperialist, picturesque, sublime or scientistic tropes. In walking this line, Back’s work offers an aesthetics of the pragmatic that anticipates John Dewey’s conception of art; in this configuration, art does not “create the forms” in a landscape, but rather employs “selection and organization in such ways as to enhance, prolong and purify the perceptual experience” (see Dewey's essay “Experience, Nature and Art” in John Dewey: The Later Works, 1925-53, Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1981; 292). Clearly, Back was not only aware of the necessary acts and extreme difficulties of an expedition, but also of the complex role undertaken by the artist-explorer, the issues surrounding the demystification of the Arctic, and the need to appeal to both the British public and the government who funded the expeditions. What he “selects” and how he “organizes” his images, therefore, is indicative of the complex requirements of his post but does not finally succumb to any single theory of landscape art. This exhibit argues that Back's refusal to force the Arctic into predetermined, singular aesthetic conventions reinforces this landscape's intrigue and its status as “other,” perhaps even more other than southern geographical subjects of imperialist exploration (see Robert David's argument to this effect in The Arctic in the British Imagination, New York: Manchester UP, 2000).