Creation Date

1828

Height

12 cm

Width

19 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

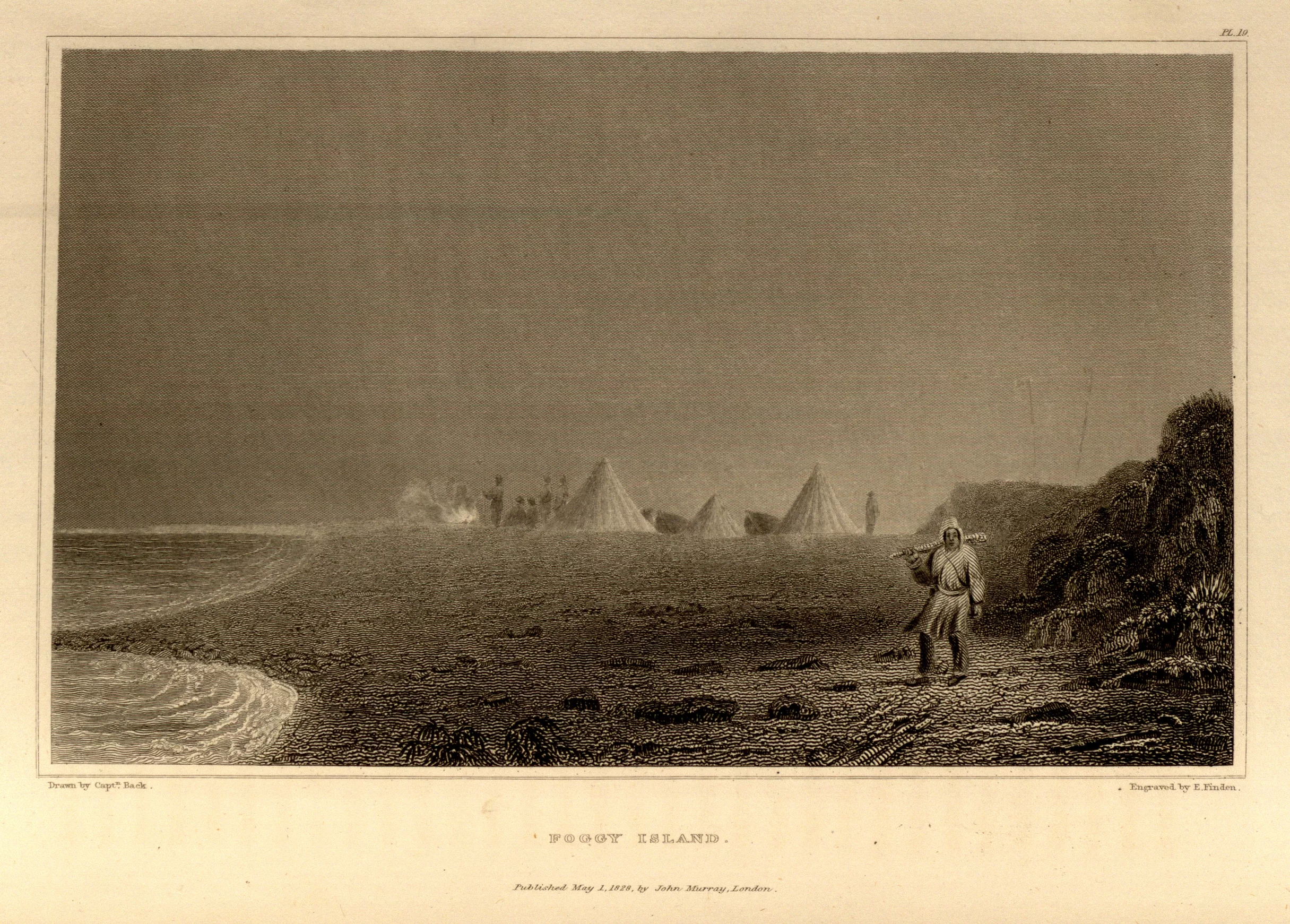

This image is primarily remarkable for its dissimilarity to other images by Sir George Back. "Foggy Island" is partially a realistic depiction of a certain stage of Franklin's journey, in which the team was caught in fog; partially a portrait of an anonymous man (unmentioned in the narrative) who seems to be an "Esquimaux"; and partially an example of what Russell Potter calls the "Arctic Sublime."

A man, apparently one of the “Esquimaux,” stands in the right quarter of the frame with a club on his shoulder, looking directly at the artist/viewer. He is on a beach. Against the foggy sky in the background there are dim images of teepees (or tents) and the hulls of boats; a few men stand around a fire. A vague pool of light illumines the man. A calm sea comes into shore on the left.

Stuart C. Houston notes that:

The world’s greatest naval power and its underemployed navy after the end of the Napoleonic Wars found the continued presence of large blank areas on the world map an irresistible challenge. John Barrow, the powerful second secretary to the Admiralty, had strong backing from the newly important scientific community to renew the search for the Northwest Passage after a long wartime hiatus. (xiv)

In addition to simply providing visual aids for a travel narrative, then, Back’s images must be seen as integral to the literal illustration of those “large blank areas” that Britain wanted to conquer. Expedition imagery during the Romantic period addressed other needs as well, including the translation of “otherness”—which the Arctic so easily exemplified in its comparatively uninhabited starkness—into a culturally understandable, and thus accessible, space for national expansionism and the application of identity. Furthermore, in ostensibly drawing accurate portrayals of the landscape (which Franklin frequently confirms), Back created scientific records designed to both titillate and inform the British public and scientific community.

More a portrait than anything else, “Foggy Island” defeats the picturesque convention of variation via the foggy atmosphere and plain setting, instead suggesting the sublime in the unknowability of the landscape—an effect emphasized by the obscurity of the fog. It is also another instance in which John Franklin refers directly to "The annexed sketch taken by Lieutenant Back," which, he says,

conveys a better picture of our encampment, and of the murkiness of the atmosphere, than any description of mine could do, and points out the propriety of designating this dreary place by the name of Foggy Island. As an instance of the illusion occasioned by the fog, I may mention that our hunters sallied forth, on more than one occasion, to fire at what they supposed to be deer, on the bank about one hundred yards from the tents, which, to their surprise, took wing, and proved to be cranes and geese. (Narrative 155)

In this case, the "illusion" is arguably an allusion (if not directly intended, still worthy of notice) to the Romantic obsession with phantasmagoria and the uncanny effects that such phenomena and corresponding artwork had on the viewer. The deer—a large, terrestrial animal—appears to transform and take wing when it is seen in its "true" form as a group of "cranes and geese." At the same time, this observation could also be interpreted as dry and didactic, in keeping with the rest of Franklin's writing: a record, merely, of the well-known problems inherent to hunting and navigating in a thick fog. Interestingly, Franklin completely ignores the man who is arguably the subject of the engraving, a fact which is all the more remarkable given how infrequently Back made images in which the subject's gaze meets that of the viewer/artist. The pool of light around the "Esquimaux" further heightens the strangeness of an already uncanny image.

Locations Description

Latitude and longitude indicate that Franklin led this expedition approximately 3-4 miles off the northeast coast of Alaska, passing through the appropriately-named Foggy Island Bay.

Publisher

John Murray

Collection

Accession Number

Thordarson T 1872

Additional Information

Bibliography

Ames, Van Meter. “John Dewey as Aesthetician.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 12.2 (1953): 145-68. Print.

Back, George. Arctic Artist: The Journal and Paintings of George Back, Midshipman with Franklin, 1819-1822. Ed. C. Stuart Houston. Buffalo: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1994. Print.

---. Narrative of the Arctic Land Expedition to the Mouth of the Great Fish River and along the Shores of the Arctic Ocean, in the Years 1833, 1834, and 1835. London: 1836. Print.

Broglio, Ron. Technologies of the Picturesque: British Art, Poetry, and Instruments, 1750-1830. Lewisburg: Bucknell UP, 2008. Print.

Canada Department of Mines and Technical Surveys, Geographical Branch. An Introduction to the Geography of The Canadian Arctic. Edmond Cloutier: Ottawa, 1951. Print.

Daston, Lorraine and Peter Gallison. Objectivity. New York: Zone Books, 2007. Print.

David, Robert G. The Arctic in the British Imagination. New York: Manchester UP, 2000. Print.

Dewey, John. “Experience, Nature and Art.” John Dewey: The Later Works, 1925-53. Ed. Jo Ann Boydston. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1981. 266-95. Print.

Dewey, John. “The Practical Character of Reality.” Pragmatism: The Classic Writings. Ed. H.S. Thayer. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1982. 275-289. Print.

Feldman, Jessica R. Victorian Modernism: Pragmatism and the Varieties of Aesthetic Experience. New York: Cambridge UP, 2002. Print.

Franklin, John. Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea, in the Years 1825, 1826, and 1827. London, 1828. Print.

Heringman, Noah, ed. Romantic Science: The Literary Forms of Natural History. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2003. Print. Suny Series in the Long Nineteenth Century.

---. Introduction. Heringman 1-22.

---. “The Rock Record and Romantic Narratives of the Earth.” Heringman 53-85.

Houston, C. Stuart. Introduction. Arctic Artist: The Journal and Paintings of George Back, Midshipman with Franklin, 1819-1822. By George Back. Ed. Houston. Buffalo: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1994. xiii-xxvi. Print.

Labbe, Jacqueline M. Romantic Visualities: Landscape, Gender and Romanticism. London: Macmillan, 1998. Print.

Levin, Jonathan. “The Esthetics of Pragmatism.” American Literary History. 6.4 (1994): 658-83. Print.

Maclaren, I.S. “Commentary: The Aesthetics of Back’s Writing and Painting.” Arctic Artist: The Journal and Paintings of George Back, Midshipman with Franklin, 1819-1822. By George Back. Ed. C. Stuart Houston. Buffalo: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1994. 275-310. Print.

Markham, Sir Clements R. The Lands of Silence: A History of Arctic and Antarctic Exploration. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1921. Print.

Meisel, Martin. Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-century England. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1983. Print.

Potter, Russell A. Arctic Spectacles: The Frozen North in Visual Culture, 1818-1875. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007. Print.

Price, Uvedale. “Essays on the Picturesque, as compared with the Sublime and the Beautiful; and on the Use of studying Pictures, for the Purpose of improving real Landscape (Vol. 1, 1810)." The Picturesque: Literary Sources and Documents. Vol. 2. Ed. Malcolm Andrews. Robertsbridge: Helm Information, 1994. 72-142. Print.

Rescher, Nicholas. Realistic Pragmatism: An Introduction to Pragmatic Philosophy. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2000. Print.

Steele, Peter. The Man who Mapped the Arctic. Vancouver: Raincoast Books, 2003. Print.

Twyman, Michael. “Haghe, Louis (1806–1885).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Web. 6 Apr. 2009.

Verner, Coolie. Explorers’ Maps of the Canadian Arctic 1818-1860. B.V. Gutsell: Toronto, 1972. Print.

Wilson, Eric. The Spiritual History of Ice. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. Print.

Woodring, Carl. Nature into Art: Cultural Transformations in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1989. Print.