Creation Date

1 November 1820

Height

14 cm

Width

23 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

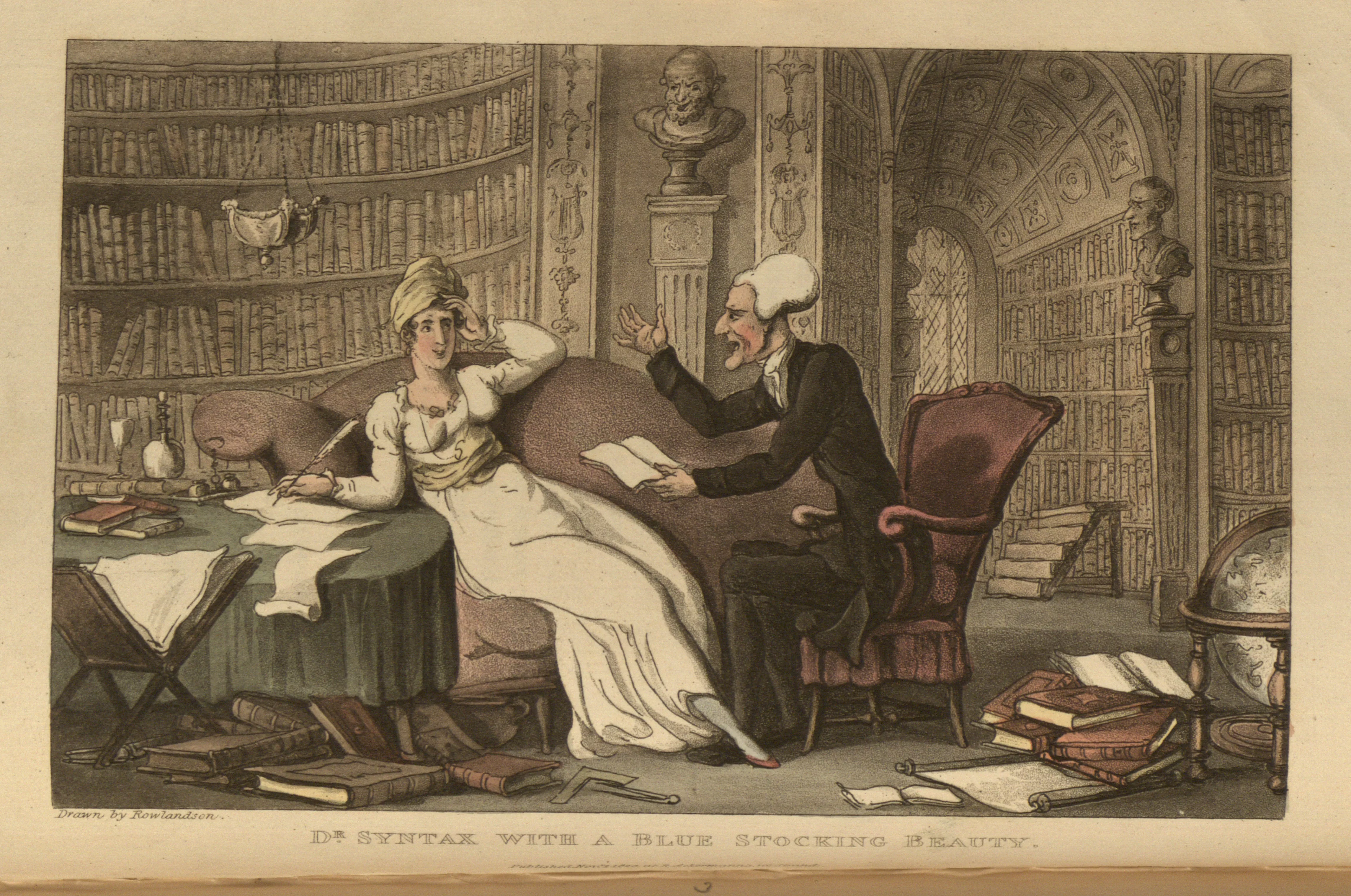

This print depicts the moment in Combe's text when Doctor Syntax makes a sexual advance towards his hostess, the beautiful bluestocking Mrs. Omicron. The piece employs and satirizes the figure of the "bluestocking," a woman who displayed or affected interest in intellectual subjects and who seemed to spurn marriage as a worthwhile pursuit.

This print depicts Dr. Syntax with his hostess, the beautiful bluestocking, Mrs. Omicron. She sits half reclined on a couch in a pose suggesting the famous portraits of Madame Recamier. Syntax reads a poem aloud while sitting on a chair in front of her. He raises his right arm and gesticulates with his hand; in this fit of passion, Syntax presses his left foot against Omicron’s leg. Apparently shocked by this outburst, she raises her left hand to her brow. Her other arm rests against the nearby table, and in her right hand she holds a quill-pen to paper as though she has been interrupted in the act of writing. Omicron wears a fashionable, white, long-sleeved and empire-waisted dress, bound at the waist with a sash, as well as a pale yellow turban. The outline of her torso and legs is clearly visible beneath the clinging fabric, as was fashionable at the time. The dress has slight ruffles at the neckline and cuffs, and Omicron wears a simple necklace. Her legs are clad in pale blue stockings and red shoes. Syntax is wearing his usual parson’s uniform: a plain black suit, stockings, and shoes; and a white cravat and wig. The pair sit in an elegant library with multiple alcoves of floor-to-ceiling shelves, crammed with books and interspersed with classical busts on elaborate, columnar pedestals. More books are strewn across the floor together with maps, a square angel, and a drafting compass. A chamber pot is visible underneath the couch. In the right foreground a large globe rests in a wooden stand. In the left foreground there is a wooden cradle for perusing looseleaf prints. Between this and the couch is the aforementioned table, hung with green baize cloth and topped with more books, an inkstand, a decanter, and a wine glass.

This print is part of a narrative that presents the bluestocking as an artistic type, linking her with the connoisseur and the fashionable woman. Mrs. Omicron is a “fair Lady” who combines “the beauties of the form and mind.” As a wealthy window, she has been much pursued by various suitors, but insists that she will only wed herself

To one with ancient learning fraught,

With all that modern science taught,

And in whose talents might be trac’d

The seeds of genius and of taste.

For one endued with such a mind (br/She’d leave exterior grace behind:

A scholar and a virtuous sage,

Whate’er his shape, whate’er his age,

Would her discerning heart engage.

(Combe 93)

Omicron herself possesses the “seeds of genius and of taste.” This is evidenced not only by her learning but also by her house, so that her supper “was in tasteful order set / In an adjoining cabinet, / Whose classic paintings like the rest, / The genius of the place confest” (99). She takes Syntax on a tour of her landscape gardens and collects classical statuary, but Omicron also creates herself as art through the medium of fashion:

She now appear’d in all the pride

Of figure and of ton beside:

Her form was fine, for plastic nature

Had work’d with pleasure on her stature.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

And though Old Time, that scurvy fellow,

Had brought her to be more than mellow;

Yet taste and art contriv’d to shade,

The inroads which his hand had made.

The Doctor view’d her too and fro,

And eye’d her form from top to toe;

Transfix’d he stood by wild surprize, [sic]

Told by his tongue and by his eyes,

And stammer’d, for he scare could speak

A line in Latin, then in Greek.

(Combe 104-105)

Omicron is pleased by Syntax’s obvious appreciation of her appearance, and in this sense she is just as vain as another feminine artistic type, the accomplished woman. Indeed, the bluestocking was often disparaged as displaying affectation rather than sincere intellectual interest (Myers 294).

Whereas the accomplished woman pursued drawing and music in order to attract a husband, the bluestocking pursued literature and scholarship for her own gratification, so that despite Omicron’s engagement with fashion and social life she seems fundamentally uninterested in marriage. The bluestocking’s egotistical pursuit of education is conveyed via Omicron’s self-absorption, which Syntax critiques in a letter he writes to his hostess protesting her cavalier treatment of him:

—And now, as I am taking leave,

Deign, my kind counsel to receive.

You laugh at others, and what then?

They may return the laugh again.

How ready’s your sarcastic word,

With She’s a fright, and He’s absurd!

But while at other’s faults you frown,

Think you, alas, that you have none?

‘Tis time, if I have eyes to see,

To quit your frisky mockery,

In five years you’ll be Forty-three!

(Combe 106)

The repeated references to Omicron’s advancing age enable Syntax to ridicule the figure of the bluestocking, suggesting that such women posed an intellectual and psychological threat to the patriarchy. The print and its surrounding narrative, however, ultimately present an ambiguous picture of the bluestocking. On the one hand, Syntax’s criticism of Omicron presents her as a failed artistic type, as someone who cannot successfully fashion herself as an enduring work of art. Yet Syntax’s criticism could also be taken as further evidence of his own foolishness; it is he, after all, who constitutes the book’s primary object of ridicule. Omicron may be refusing Syntax’s advances because her bluestocking identity is a sham and she does not sincerely want a man of intellect, or because she does desire an intellectual husband and the foolish Dr. Syntax falls far short of her requirements. Furthermore, although Omicron’s rejection of Syntax is represented in both the print and the accompanying text as self-conscious and exaggerated, her moral outrage is still in keeping with the bluestocking type. The British bluestocking appropriated the literary interests, luxury, and refined taste of Parisian hostesses, but imbued that salon tradition with a sense of distinct moral purpose (Eger, “Luxury, Industry, and Charity” 192).

Locations Description

This image is set in the library of a country house. Dedicated libraries were relatively new rooms in private residences of the early-nineteenth century. Their inclusion indicates the growth of print culture during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and the changing organization of country houses. Both books and prints were kept in libraries; the latter were usually framed in simple mats and kept in a cradle for easy browsing. A growing emphasis on informal social interaction encouraged the use of libraries as relatively casual spaces where hosts and guests of different ages and genders could interact. As a site where both men and women could come together to converse in the mutual pursuit of literary, intellectual, and artistic advancement, the library is highly suggestive of the bluestocking salons. As the nineteenth century progressed, however, libraries would become increasingly gendered as masculine spaces and grouped with billiard and smoking rooms in the patriarchal domain of the Victorian country house.

Publisher

Rudolph Ackermann

Collection

Accession Number

Thordarson T 576

Additional Information

Bibliography

"bluestocking, adj. and n." OED Online. June 2013. Oxford UP. 20 August 2013.

Bodek, Eevelyn Gordon. “Salonières and Bluestockings: Educated Obsolescence and Germinating Feminism.” Feminist Studies 3 (1976): 185-99. Print.

Brink, J.R., ed. Female Scholars: A Tradition of Learned Women before 1800. Montreal: Eden Press Women’s Publications, 1980. Print.

Combe, William. The Third Tour of Dr. Syntax: In Search of a Wife: a Poem. London, 1821. Print.

Eger, Elizabeth. “Luxury, Industry and Charity: Bluestocking Culture Displayed.” Luxury in the Eighteenth Century: Debates, Desires and Delectable Goods. Ed. Maxine Berg and Elizabeth Eger. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. Print.

Eger, Elizabeth, et. al., eds. Women, Writing, and the Public Sphere, 1700-1830. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2001. Print.

Ferguson, Moira, ed. First Feminists: British Women Writers, 1578-1799. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1985. Print.

Ford, John. Ackermann, 1783-1983: The Business of Art. London: Ackermann, 1983. Print.

Gilbert, Sandra M., and Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. New Haven: Yale UP, 1979. Print.

Heller, Deborah. “Bluestocking Salons and the Public Sphere.” Eighteenth-Century Life 22 (1998): 59-82. Print.

Martin, Jane Roland. Reclaiming a Conversation: The Ideal of the Educated Woman. New Haven: Yale UP, 1985. Print.

Myers, Sylvia Harcstark. The Bluestocking Circle: Women, Friendship, and the Life of the Mind in Eighteenth-Century England. Oxford: Claredon, 1990. Print.

Nussbaum, Felicity A. The Limits of the Human: Fictions of Anomaly, Race, and Gender in the Long Eighteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

Purvis, June. “Towards a History of Women’s Education in Nineteenth-Century Britain: A Sociological Analysis.” Westminster Studies in Education 4 (1981): 52-71. Print.

Rizzo, Betty. Companions Without Vows: Relationships Among Eighteenth-Century British Women. Athens: U of Georgia P, 1994. Print.

Spencer, Jane. The Rise of the Woman Novelist: From Aphra Behn to Jane Austen. Oxford: Blackwell, 1986. Print.

Spender, Dale. Women of Ideas and What Men Have Done to Them: From Aphra Behn to Adrienne Rich. London: Routledge, 1982. Print.

Williamson, Marilyn L. “Who’s Afraid of Mrs. Barbauld? The Blue Stockings and Feminism.” International Journal of Women’s Studies 3 (1980): 89-102. Print.