Creation Date

1 May 1812

Medium

Genre

Description

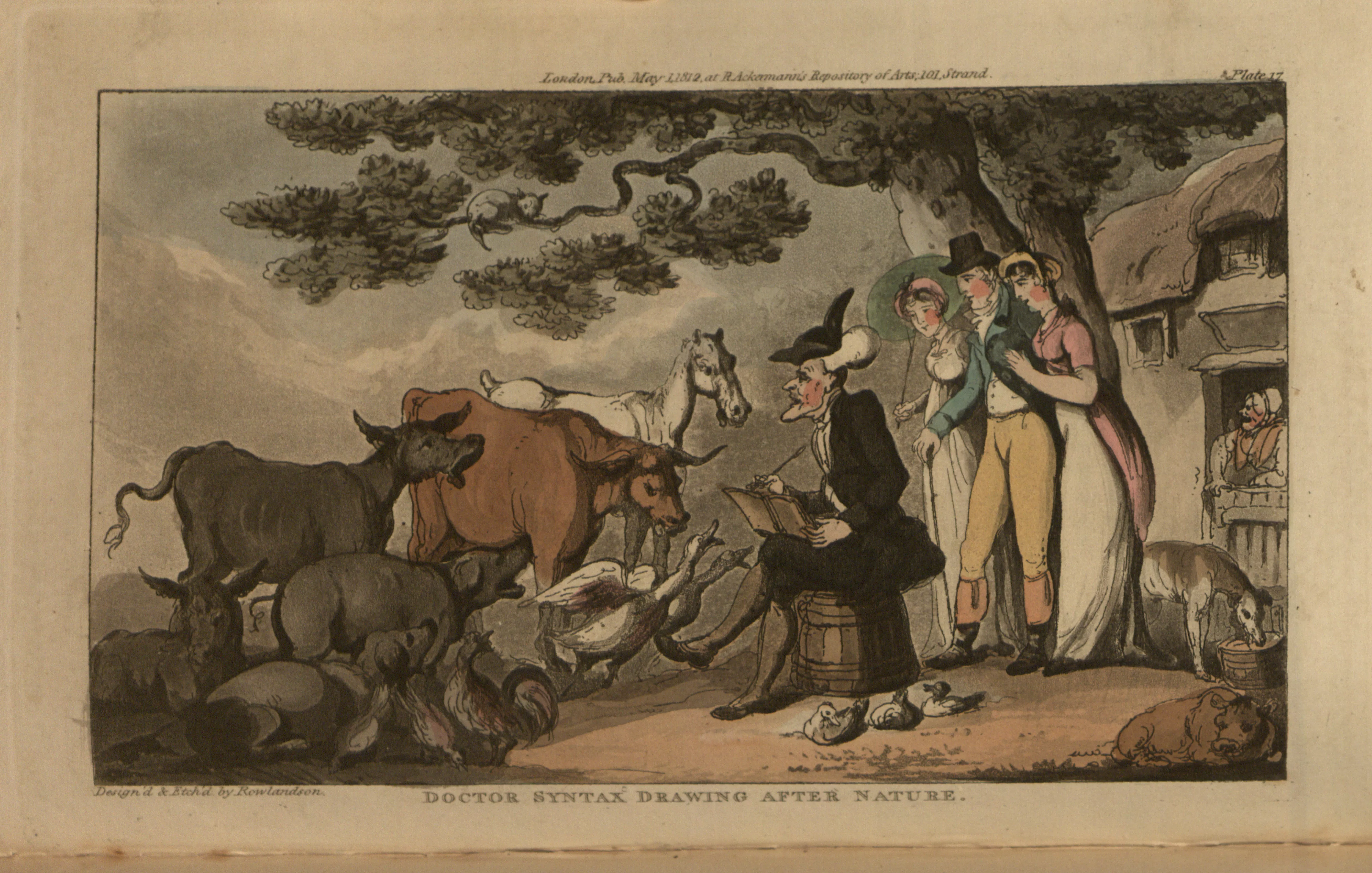

This print accompanies a chapter in which Dr. Syntax meets a country squire and announces that only farm animals would be proper subjects for his picturesque drawings. The squire invites Syntax back to his country house, introduces him to his wife and sister, and the group goes to the squire’s home farm where Syntax can sketch domestic animals from life. Syntax is in the center of the print, surrounded by the farm animals he draws, and he is observed by the country squire, the two ladies, and a farm woman. It is the presence of this last person that provides the key to the main satire of the piece: Syntax's decision to sketch domestic animals not only pokes fun at his apparent lack of "taste," but also belittles the activities and preoccupations of the picturesque tourist in contrast with the poverty and hard work of the propertyless tenants.

Dr. Syntax is in the center of the print, sitting on an overturned washtub and drawing in his sketchbook. In front of him to the left are a bevy of farm animals, including Syntax’s own donkey, Grizzle, a cow and calf, another donkey, a pig, a sheep, geese, chickens, and ducks. The squire stands behind Syntax with a lady on each arm, a tree arching over them. A thatched-roof cottage borders the right edge of the print; a woman, presumably a laborer on the squire’s farm, leans out of the half-open doorway. She wears an uncolored dress and bonnet, with a tan shawl over her shoulders. Syntax is dressed in his usual parson’s uniform: a plain black suit and shoes, dark stockings, a white shirt and cravat, and an old-fashioned wig with a black tricorn hat. The squire wears fawn-colored trousers and tall leather boots; a white waistcoat, shirt, and cravat; a blue coat, and a black top hat. He carries a walking stick. The ladies are wearing fashionable, white, empire-waist dresses. The lady on the left also wears a pink turban and carries a green parasol, while the lady on the right wears a pink overdress and straw bonnet.

This print is part of a series in William Combe and Thomas Rowlandson’s collaborative work satirizing the picturesque tour. The picturesque tour served as a domestic replacement for the Grand Tour during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars made continental travel difficult. As a result, the picturesque tour emphasized British sites, buildings and monuments as well as “natural” scenery. The usual object was recreational amusement and aesthetic enjoyment, but Dr. Syntax hopes to publish an account of his own tour, complete with sketches, that will make his fortune. This depiction of the commercialization of the picturesque tour indicates the extent to which the practice was implicated in the nascent tourism industry.

This image draws a contrast between the aesthetic categories of the picturesque and the beautiful as well as between the gentry and working classes who inhabited the same rural landscapes. Dr. Syntax is an amateur artist obsessed with the picturesque as a precisely defined aesthetic category, and so he dismisses those sites that might rather fall into the aesthetic category of the beautiful. Consequently, when the squire’s sister asks him to draw her portrait, he replies:

In vain, fair maid, my art would trace

Those winning smiles, that native grace.

The beams of beauty I disclaim;--

The picturesque’s my only aim:

My pencil’s skill is mostly shown

In drawing faces like my own,

Where Time, alas, and anxious Care,

Have plac’d so many wrinkles there.

(Combe 121)

The young lady, described as “a laughing elf,” is clearly poking fun at Syntax and is conscious of her own superior taste. Unlike the landed gentry, Syntax has no true taste for the beautiful, and thus his status as an artistic type is questioned and parodied.

Syntax’s myopic view of the picturesque farm animals, to the exclusion of the potential beauties of the surrounding countryside, also suggests that he is incapable of exercising proper political authority. Syntax’s inability to take in the broad view figuratively marks him as vulgar: it is precisely the landowner’s ability to view an entire prospect—that is, to think in general terms and extract abstract ideas from concrete experience—that, presumably, justifies his claim to political power (Barrell). If landowners like the squire pictured in this print were perceived as proper political leaders because they were thought to have an inherent interest in the public good, then Syntax represents the bourgeois individual whose private interests and desire for personal profit make him unfit for leadership in the public sphere. That Dr. Syntax is a minister whose object is to make a fortune from publishing an account of his picturesque tour adds to the satirical edge, implying that ministers care less for their public duties than for their own private income.

Though Syntax is rendered ridiculous in his vulgarity and self-interestedness, the print arguably represents the aesthetic warfare between the amateur artist and his hosts as yet more absurd. Their banter and superficial concerns, the petty occupations of the leisure class, seem insignificant when compared to the life of the female farm laborer represented on the print’s right-hand margin. Though implicated in the privilege and uselessness of such debate, Syntax traverses a potentially liminal space as a tourist. As a gentleman traveler, Syntax is more or less in the same class as the squire and his family, yet he has just as little legal claim to the local landscape as the squire’s employee. Further pushing this interesting parallel between the minister and the laborer, Syntax, perhaps unwittingly, privileges the values of rural life over upper-class tastes when he chooses farm animals as the subject of his picturesque drawing. This print thus suggests how the picturesque tourist could negotiate the boundary between country life, as lived by the landed gentry, and rural life, as lived by their tenant farmers and laborers: the relative freedom of the tourist to move between differently classed spaces speaks to the possibilities of tourism as a practice for the formation of autonomous individual identity.

Locations Description

This image depicts the home farm of a country squire. Country landowners usually owned various farms, operated by tenants, in addition to a single home farm that produced food for the direct consumption of the squire and his family. Such farms were usually worked by hired laborers who might be longstanding employees but who did not have any lease or indirect ownership of the land they worked. Although in France the home farm was often directly adjacent to the chateau in the basse-cour (the farmyard), in Britain it was usually placed well away from the big house so as not to interfere with either the squire’s residence or his picturesque landscape gardens.

Publisher

Rudolph Ackermann

Collection

Accession Number

Thordarson T 574

Additional Information

Bibliography

Andrews, Malcolm. The Search for the Picturesque: Landscape Aesthetics and Tourism in Britain, 1760-1800. Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1989. Print.

Barbier, Carl Paul. William Gilpin: His Drawings, Teaching, and Theory of the Picturesque. Oxford: Clarendon, 1963. Print.

Barrell, John. The Birth of Pandora and the Division of Knowledge. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1992. 41-61. Print. New Cultural Studies Series.

Bermingham, Ann. Learning to Draw: Studies in the Cultural History of a Polite and Useful Art. New Haven: Yale UP, 2000. Print. The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

---. “System, Order, and Abstraction: The Politics of Landscape Drawing around 1795.” Landscape and Power. Ed. W.J.T. Mitchell. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1994.

Casid, Jill H. Sowing Empire: Landscape and Colonization. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2005. Print.

Combe, William. The Tour of Dr. Syntax: In Search of the Picturesque: a Poem. London: Ackermann's Repository of Arts, 1812. Print.

Copley, Stephen. “Gilpin on the Wye: Tourists, Tintern Abbey, and the Picturesque.” Prospects for the Nation: Recent Essays in British landscape, 1750-1880. Ed. Michael Rosenthal, Christiana Payne, and Scott Wilcox. New Haven: Yale UP, 1997. Print. The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

Copley, Stephen and Peter Gartside, eds. The Politics of the Picturesque: Literature, Landscape, and Aesthetics since 1770. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1994. Print.

Fabricant, Carole. “The Aesthetics and Politics of Landscape in the Eighteenth-Century.” Studies in Eighteenth-Century British Art and Aesthetics. Ed. Ralph Cohen. Berkeley: The U of California P, 1985. Print.

---. “The Literature of Domestic Tourism.” The New Eighteenth Century. Ed. Felicity Nussbaum and Laura Brown. New York: Methuen, 1987. Print.

Ford, John. Ackermann, 1783-1983: The Business of Art. London: Ackermann, 1983. Print.

George, M. Dorothy. Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires in the British Museum. Vol. 8. London: by order of the Trustees, 1947. Print.

---. British Museum Satires. 1809 ed. Catalog nos.11507-11516. London: by order of the Trustees, 1809. Print.

British Museum Satires. 2nd Vol. Catalog nos. 11672-11689. London: by order of the Trustees, 1810-1811.

Gilpin, William. Three Essays: --on Picturesque Beauty; --on Picturesque Travel; and, on Sketching Landscape: to which is added a Poem, on Landscape Painting. London, 1792. Print.

Girouard, Mark. Life in the English Country House: a Social and Architectural History. New York: Penguin, 1980. Print.

---. Life in the French Country House. New York: Knopf, 2000. Print.

Harris, John. The Artist and the Country House: A History of Country House and Garden View Painting in Britain, 1540-1870. London: Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1979. Print.

Moir, Esther. The Discovery of Britain: The English Tourists 1540-1840. London: Routledge, 1964. Print.

Price, Uvedale. An Essay on the Picturesque, as Compared with the Sublime and the Beautiful; and, on the Use of Studying Pictures, for the Purpose of Improving Real Landscape. 2 vols. London, 1810. Print.

Sha, Richard C. The Visual and Verbal Sketch in British Romanticism. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania UP, 1998. Print.

Standring, Timothy J. “Watercolour Landscape Sketching During the Popular Picturesque Era in Britain.” Glorious Nature: British Landscape Painting, 1750-1850. New York: Hudson Hills, 1993. Print.

Stebbins, Robert A. Amateurs, Professionals and Serious Leisure. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1992. Print.