Creation Date

c.1808–09

Height

11.1 cm

Width

15.6 cm

Medium

Description

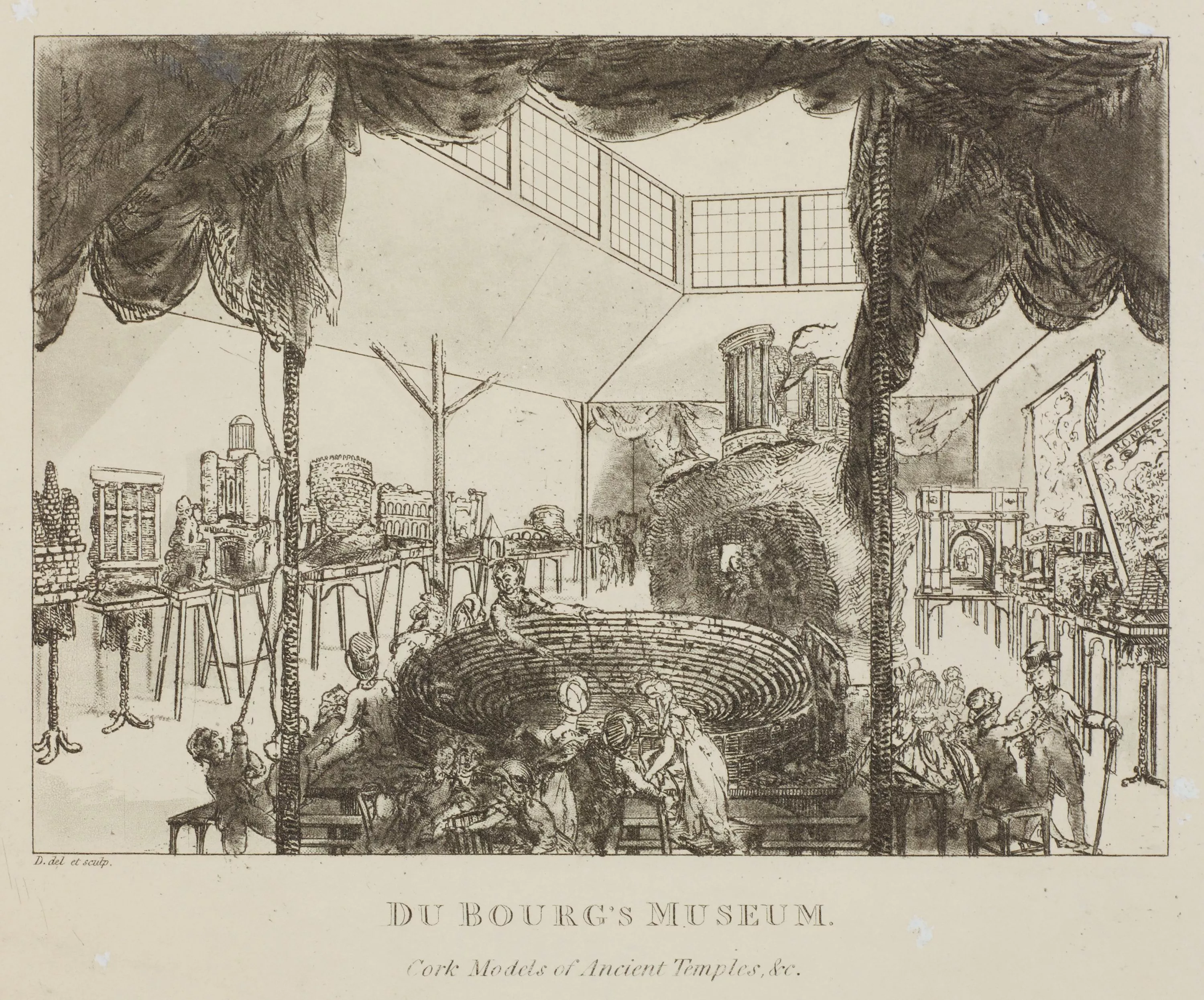

This engraving depicts Richard Du Bourg’s collection of cork models, which at the time of this image’s creation (1808-9) was housed at 68 Grosvenor Street, London. While a few of the models lining the perimeter of the exhibition room represent Gothic or Greek architecture, the vast majority of the twenty-eight on display replicate Roman buildings from sites in Italy and southern France, a theme completed by a map of the ancient city of Rome, visible on the right-hand wall. The two central exhibits, illuminated by a set of clerestory windows set in the ceiling, are models of the amphitheater at Verona and the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli. In the immediate foreground of the image, a suspended curtain is being raised by what appears to be a young man or child, possibly an assistant to Du Bourg (see Arnott-Davies 2–3). With a true showman’s flourish, Du Bourg suggests that the scene here is being revealed the very moment the viewer gazes at the engraving.

A crowd of mixed ages and sexes surrounds the model of the amphitheater at Verona, attending to a lecture led by Du Bourg himself (seen here gesturing with a baton to a particular feature of the model). The imposing model of the Temple of Vesta sits on a large rock, creating a facsimile of the terrain—including a mock tree—on which the original temple is situated. Although it is difficult to discern, each model was set within, or upon, a simulation of its ‘real’ environment, using various materials such as sand and moss to create naturalistic effects. Two curtained spaces in the rear corners of the room were reserved for Du Bourg’s “multimedia” exhibits, which were staged hourly. One was a model of the “Sybil’s Temple and Cascade of Tivoli” (complete with an actual waterfall), while the other replicated “a view of Vesuvius erupting and threatening the town of Portici in 1767 and the dramatic cataract of lava and fire in the eruption of 1771” (Gillespie, “Richard Du Bourg’s ‘Classical Exhibition,’” 262). The latter exhibit involved special effects created by sound, light, and burning sulpher, as vividly described in the account of the visiting American scientist Benjamin Silliman:

We were conducted behind a curtain where all was dark, and through a door or window, opened for the purpose, we perceived Mount Vesuvius throwing out fire, red hot stones, smoke and flame, attended with a roaring noise like thunder; the crater glowed with heat, and, near it, the lava had burst through the side of the mountain, and poured down a torrent of liquid fire… (Silliman, vol. 1, 199–200)

The wondrous as well as didactic appeal of such carefully contrived exhibits is most likely what incites the spectators’ apparent enthusiasm. They do not simply shuffle past the models; rather, they crowd, jostle, point, and talk to one another.

Du Bourg’s exhibitions of classical models were a prominent feature of London’s museum landscape for nearly fifty years. They passed through various locations in the years between 1775 and 1785, including at his own residence in Duke Street and in rented rooms at Spring Gardens. Newspaper accounts convey how well these early exhibitions were received:

[the models] are all executed in cork, stained and done in such an exact manner, as conveys to the beholder the most lively idea of the originals; the mouldering of the stones, the crevices in the walls, &c. are executed with the greatest nicety, the very moss on the buildings, and on the ruins which are scattered about them, are finished to the greatest minutiae of exactness . . . There was a very genteel company there; among whom was a Gentleman just come from Rome, who declared he thought it impossible for human art to copy so closely the originals. (Morning Post and Daily Advertiser, 5 May 1779)

It is believed that in 1785 much of Du Bourg’s collection was destroyed, in a tragic turn of fate, in a fire caused by an earlier iteration of the Vesuvius model. However, a model of the Roman Colosseum appears to have survived and is now in the collections of Museums Victoria. Du Bourg eventually established a more permanent exhibition in new premises in Lower Grosvenor Street, which were open to visitors from 1799 until the collection was finally sold in 1819. Cork models such as Du Bourg’s were sought after by wealthy collectors, and his exhibitions attracted a wide and diverse audience—from royalty, to merchants, to children. This engraving was used on a handbill advertising the show (Gillespie, “Richard Du Bourg’s ‘Classical Exhibition,’” 262). As the only surviving illustration of Du Bourg’s collection of models, it furthers our understanding of the history—and display—of architectural modeling in Romantic-era London.

The true value of Du Bourg’s museum was that he brought the Classical world to Londoners who otherwise had to rely on the comparatively uninspiring images found in books. Du Bourg’s models were more accessible (and much more transportable) than the originals, and therefore served as important educational tools. By traveling to Italy (he had first acquired his skills in cork modeling while in Rome in the 1760s), carefully measuring classical Roman buildings, and then scaling them down himself (or, in some cases, by using the measurements recorded by other traveling scholars of architecture, such as John Soane), Du Bourg could offer a tangible and informative experience of the classical world without incurring the expense of a Grand Tour. Through their accuracy, novelty, and theatricality, Du Bourg’s models reflected— and satisfied—a desire to “restore a lost third dimension to those flat images that had served as an introduction to the material culture of classical antiquity” (Arnott-Davies 22). Cork, moreover, was a well-suited material for recreating ruins because of its texture and resilience.

In addition, Du Bourg’s engraving allows us to trace the origins of display strategies employed by other antiquarians of the Romantic period. In an earlier iteration of his museum, Du Bourg experimented with lighting techniques, using cleverly-placed lanterns to dramatically illuminate his collection. Having attended one of these displays in 1785, the architect and antiquarian John Soane was inspired to adopt a similar approach when he mounted a public display of the alabaster sarcophagus of Seti I some 40 years later (Arnott-Davies 14). What’s more, when commissioned by Soane to conceptualize the Dome Area of his house-museum before it was constructed, artist Joseph Gandy included at the center of his painting a model of the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli—likely the one purchased by Soane in 1804 (Gillespie, “Rise and Fall,” 125). Soane’s own collection of architectural cork models, still on display in the Model Room at the John Soane Museum in London, is a notable survivor of their fall from fashion in later nineteenth-century collections.

Associated Persons

Copyright

"Du Bourg’s Museum" by Richard Du Bourg, image © London Metropolitan Archives (City of London)

Collection

Accession Number

SC/GL/PR/W2/GRO/STR/p5416254

Bibliography

Altick, Richard. The Shows of London. Belknap/Harvard UP, 1978.

Arnott-Davies, Rees. “Rome in London: Richard Du Bourg, Cork Modelling, and the Virtual Grand Tour.” Romanticism on the Net (Special issue on “Recollecting the Nineteenth-Century Museum,” ed. Sophie Thomas), no. 70, 2018, pp. 1–26. https://ronjournal.org/articles/n70/.

Du Bourg, Richard. Mr. Du Bourg’s Exhibition of Large Models cut in Cork, of the Remains of Capital Buildings, in and near Rome and in England, to be seen At the Great Room, Spring Gardens, Late Cox’s Museum. 1785.

———. Descriptive Catalogue of Du Bourg’s Museum, No. 68, Lower Grosvenor-Street. Watts & Bridgewater, 1809.

Gillespie, Richard. “Richard Du Bourg’s ‘Classical Exhibition’, 1775-1819.” Journal of the History of Collections, vol. 29, no. 2, 2017, pp. 251–69.

———. "The Rise and Fall of Cork Model Collections in Britain." Architectural History, vol. 60, 2017, pp. 117–46.

Leigh, Samuel et al. Leigh's New Picture of London: Or A View of the Political, Religious, Medical, Literary, Municipal, Commercial, and Moral State of the British Metropolis; Presenting a luminous guide to the stranger on all subjects connected with general information, business, or amusement. To which is adjoined a description of the environs. Printed by William Clowes, 1827.

Lukacher, Brian. Joseph Gandy: An Architectural Visionary in Georgian England. Thames & Hudson, 2006.

Silliman, Benjamin. A Journal of Travels in England, Holland and Scotland, and of two passages over the Atlantic, in the years 1805 and 1806. 3 vols., 1810.

Squibb and Son (Auctioneers) and R Dubourg. A Catalogue of the Celebrated Cork Models of Mr. R. Dubourg: Forming the Exhibition at No. 68 Lower Grosvenor Street and Comprising Correct Representations of Some of the Mose Distinguished Remains of Antiquity in and near Rome Naples and the South of France. 1819.

Du Bourg’s Museum of Cork Models © 2024 by Sophie Thomas, Rhys Jeurgensen, Erin McCurdy, and Romantic Circles is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0