Exhibit

Creation Date

1839

Height

3cm

Width

4cm

Medium

Genre

Description

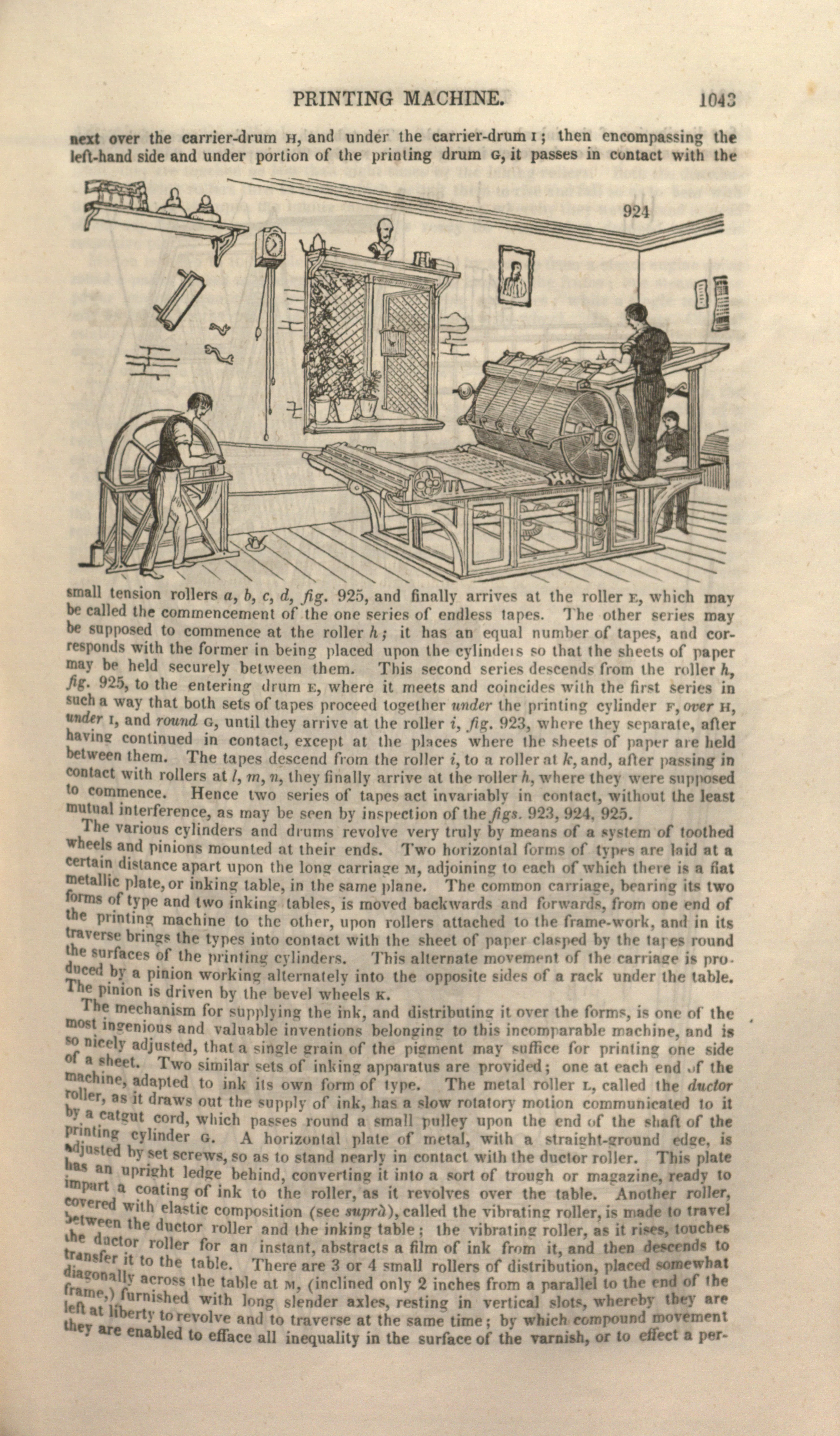

In this drawing of a printing machine patented by “Messrs. Applegath and Cowper,” two men work at the press while one man operates a fly-wheel pulley system. The figure at the back of the machine piles sheets of paper while

the boy, who stands on the adjoining platform, takes up one sheet after another and lays them upon the feeder, which has several linen girths passing across its surface, and round a pulley at each end of the feeder; so that whenever the pulleys begin to revolve, the motion of the girths carries forward the sheet, and delivers it over the entering roller. (Ure 1042)

This illustration is meant to depict the inking process after the machine has been inked and prepared:

The table thus evenly smeared, being made to pass under the 3 or 4 proper inking rollers N, fig. 924, imparts to them a uniform film of ink to be immediately transferred by them to the types. Hence each time that the forms make a complete traverse to and fro, which is requisite for the printing of every sheet, they are touched no less than eight times by the inking rollers. Both the distributing and inking rollers turn in slots, which permit them to rise and fall so as to bear with their whole weight upon the inking table and the form, whereby they never stand in need of any adjustment by screws, but are always ready for work when dropped into their respective places. Motion is given to the whole system of apparatus by a strap from a steam engine going round a pulley placed at the end of the axle at the back of the frame; one steam-horse power being adequate to drive two double printing machines; while a single machine may be driven by the power of two men acting upon a fly-wheel. (Ure 1044-45).

The factory itself is depicted as a small room with wood floors and a central, latticed window, open. The walls are decorated with printed materials (l.), a portrait of a man, a wall-mounted clock showing the time at 10:35, and a shelf with what looks like statues and books (r.). The lower window ledge supports three potted plants, and the upper ledge supports a bust and possibly books. A birdcage hangs in the open window.

Between 1811 and 1814, Frederick Koenig invented the first steam-powered printing press, which Ure calls a “printing automaton” (1040). Edward Cowper and Augustus Applegarth made several improvements to this technology and patented several steam printing presses, including a four-cylinder newsprint press in 1827 that could print up to five thousand sheets per hour. This print is meant to illustrate one of their machines.

Andrew Ure’s The Philosophy of Manufactures (1835) is Ure’s most famous work and echoes many of the sentiments expressed in the Dictionary, and this entry in particular. (This entry, moreover, includes several illustrative figures in addition to the featured image.) Ure’s work contributed to “a new literary genre” in the 1830s, that of “factory guide books” (Edwards 17). As Edwards makes clear, the book’s “fantasy of labour helped shape the industrial series and its inverse—the socialist imaginary,” as it was interpreted and read by Marx in Das Kapital (17).

This illustration of a partially steam-powered printing press is taken from an entry on “The Printing Machine” in Andrew Ure’s A Dictionary of Arts, Manufactures, and Mines (11th ed., 1847). Identifying narratives of progress, Ure’s text draws explicit parallels between popular automata and industrialization.

Rich technological, economic, social, and cultural genealogies have been made for the printing press, both in the Romantic era and in the history of printing presses and industrialization more broadly. In terms of this gallery’s focus, however, this specific representation of an automatic printing press, along with Ure’s accompanying description, offers an overt link between the production and technology of Romantic-era automata and industrialization accomplished by means of self-acting machines. In the entry on “automaton,” Ure defines the term to mean "every mechanical construction which . . . can carry on, for some time, certain movements more or less resembling the results of animal exertion, without the aid of external impulse,” and then tellingly argues that “[i]n this respect, all kinds” of machines and industrial technologies “may be denominated automatic" (83). Interestingly, the printing press depicted here still relies on human labor to power and assist its mechanism. Ure depicts the factory as an open-air room associated with learning, culture, and art. However, the workers themselves, in their performance of repetitive functions, become limbs of the machine.

Ure’s willingness to overlay “automatic” with the mimetic implications of “automata” in the above quote deconstructs the argument he wants to make. In others words, rather than depicting a progression whereby an automaton swan gives way to an automatic printing press, Ure’s text encourages us to see the printing press and the whole “factory as a vast automaton that was itself the subject of the productive process” (Edwards 20). As Marx understood in Das Kapital, Ure viewed technologies like the self-acting printing press and the automatic loom not simply as replacements for human labor, but as simulations of human labor and bodies. The Dictionary and The Philosophy of Manufactures repeatedly describe machines in bodily terms, calling attention to their hands and hearts, as if machines resembled as well as replaced human bodies (Edwards 22-23).

If we can see Ure’s printing factory in this print as a “vast automaton,” then it becomes like Kempelen’s chess player, a hybrid automaton, in which human bodies are drawn into the machine’s processes, complicating the direction of mimesis. As caricatures such as Shaving by Steam show, the automatic machine and the automatic body become increasingly intertwined and self-reflexive in the nineteenth-century, subverting the very narrative of progress that texts like Ure’s attempt to narrate.

Copyright

Copyright 2009, Department of Special Collections, Memorial Library, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI

Collection

Accession Number

Cole Coll C 997

Additional Information

Bibliography

Altick, Richard. The Shows of London. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP Belknap P, 1978. Print.

Edwards, Steve. “Factory and Fantasy in Andrew Ure.” Journal of Design History 14.1 (2001): 17-33. Print.

Greater London Council Public Relations Branch. John Joseph Merlin: The Ingenious Mechanick. London: Greater London Council, 1985. Print.

Landes, Joan. “The Anatomy of Artificial Life: An Eighteenth-Century Perspective.” Genesis Redux: Essays in the History and Philosophy of Artificial Life. Ed. Jessica Riskin. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2007. 96-116. Print.

Riskin, Jessica. “The Defecating Duck, or, the Ambiguous Origins of Artificial Life.” Critical Inquiry 29.4 (2003): 599-633. Print.

Wosk, Julie. Breaking Frame: Technology and the Visual Arts in the Nineteenth Century. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1992. Print.