Creation Date

1774

Height

15 cm

Width

13 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

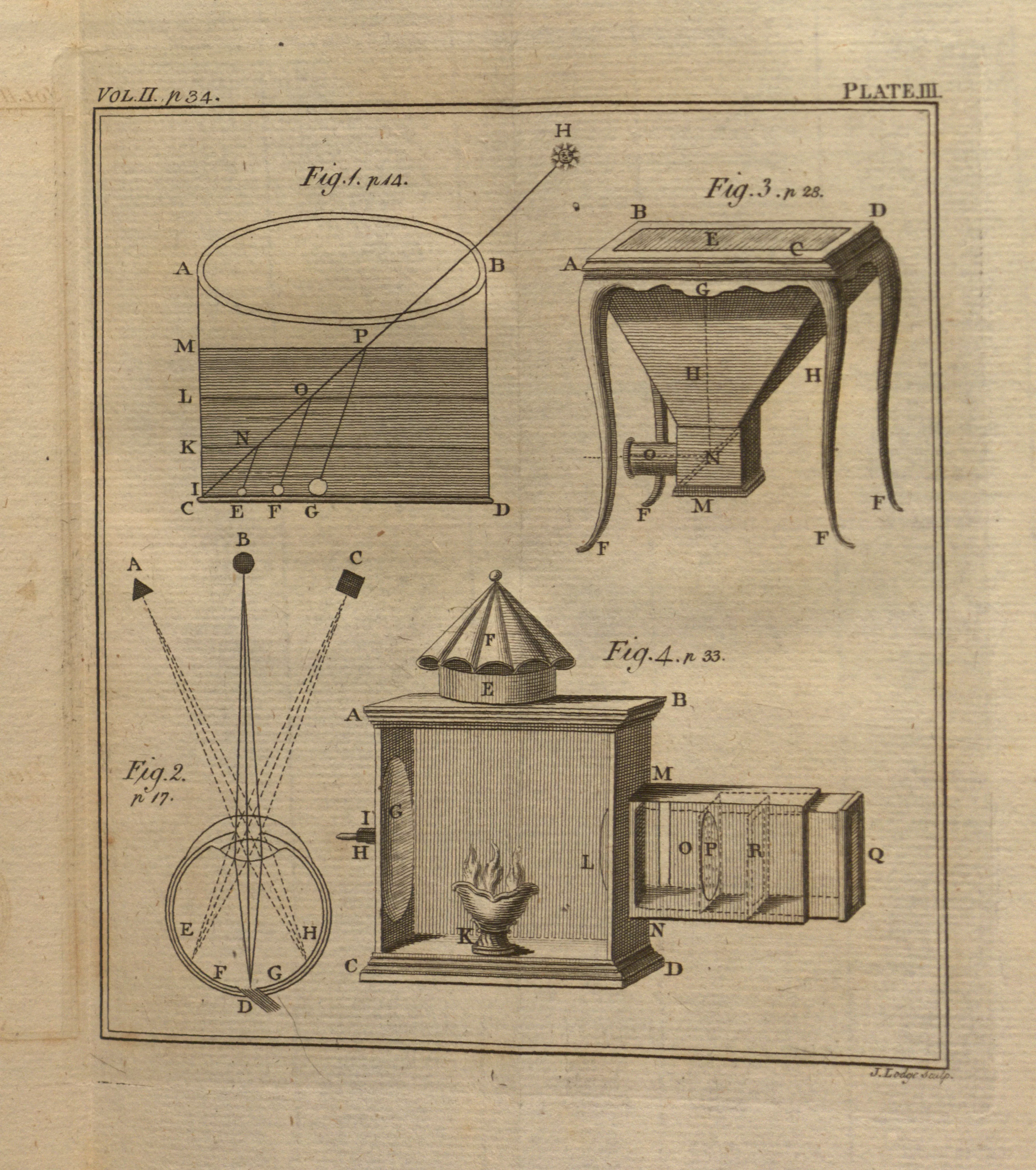

Hooper's text and its images describe how to create optical instruments for recreational scientific experiments.

“Plate III” features four illustrations of rational recreations involving optics and illusions. Figure 1 illustrates the refraction of light through water in a vessel. Figure 2 diagrams alterations in human vision based on the optic nerve receptors. Figure 3 is a portable camera obscura much like the one illustrated by Guyot in Nouvelles récréations. Figure 4 is a magic lantern. The plate accompanies instructions in the text describing how to create these optical devices and illusions.

The connection between M. Guyot’s Nouvelles recreations of 1772 and Hooper’s subsequent Rational Recreations is clearly stated in the latter author’s text and is “indicative of the later eighteenth-century tendency to publish in multiples” for particularly popular genres (Stafford 58). Hooper credits Guyot with the invention of the portable camera obscura (Figure 3), and copies the illustration of the elegant, furniture-like design from the French author almost exactly (Hooper 28). The table-like camera obscura, with the lens and mirrors hidden beneath the projection surface, evokes Barbara Maria Stafford’s conception of “furniture-to-think-with,” drawing room pieces constructed to be useful for both socialization and education in the Romantic period (Stafford, “Revealing Technologies/Magical Domains” 11). The side table style apparatus challenges Jonathan Crary’s argument that the camera obscura serves to interiorize or decorporealize vision by isolating the viewer within the apparatus. Although composed of the same basic elements as other types of camera obscura—including the focusing lens, glass mirror, and glass pane—camera-obscura-as-furniture quite literally becomes a parlor trick for group entertainment, rather than a space of isolated viewing (Crary 39).

Unlike some texts on rational recreations from this period, Hooper emphasizes the re-creative imaging potentials of the camera obscura, writing that the apparatus “affords the most perfect model for painters, as well for the tone of colors, as that degradation of shades, occasioned by the interpolation of the air, which has been so justly expressed by some modern painters” (Hooper 24). In re-creating Guyot’s original text on scientific recreations, Hooper not only reiterates the correlation between optics and illusions but also maintains the continuity of the forms and subjects of inquiry begun in the Enlightenment and carried into the Romantic period.

Collection

Accession Number

Thordarson T1990

Additional Information

Bibliography

Crary, Jonathan. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990. Print.

Groth, Helen. “Domestic Phantasmagoria: The Victorian Literary Domestic and Experimental Visuality.” South Atlantic Quarterly 108.1 (2009): 147-69. Print.

Hooper, William. Rational Recreations: In which the Principles of Numbers and Natural Philosophy are Clearly and Copiously Elucidated, by a Series of Easy, Entertaining, Interesting Experiments. London, 1774. Print.

Riskin, Jessica. “Amusing Physics.” Science and Spectacle in the European Enlightenment. Ed. Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent and Christine Blondel. Burlington: Ashgate, 2008. 43-64. Print.

Stafford, Barbara Maria. Artful Science: Enlightenment, Entertainment, and the Eclipse of Visual Education. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994. Print.

--- . “Revealing Technologies/Magical Domains.” Devices of Wonder: From the World in a Box to Images on a Screen. Ed. Barbara Maria Stafford and Frances Terpak. Los Angeles: Getty, 2001. 1-115. Print.