Exhibit

Creation Date

23 January 1815

Height

11 cm

Width

20 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

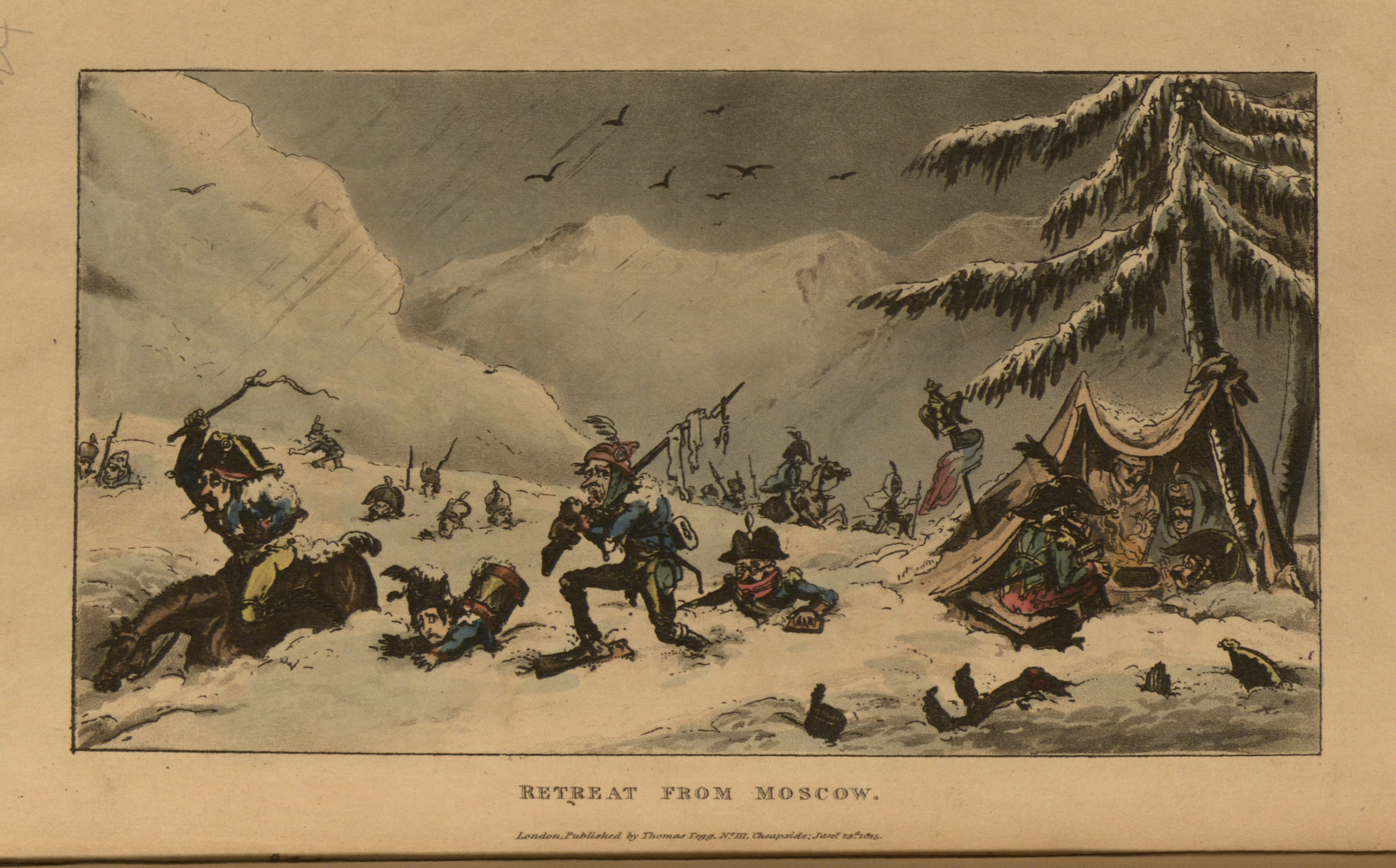

This image depicts the retreat of Napoleon and his forces from Moscow, with particular emphasis on the harsh and nightmarish conditions of their journey.

A great amount of snow covers the ground in this image. Many soldiers are partially or completely buried by it, and one soldier sits atop a horse whose legs are also buried. Each soldier wears an expression of terror. To their right, four men huddle in an open tent around a fire, a pot resting beside it. One of them is buried up to his neck in snow, and one is completely shrouded in a blanket. The only sign of plant life is a large pine tree behind the tent. One French flag remains flying near the tent.

On top of the French flag, which is flying lower than in the book's previous images, is an eagle. The eagle is a symbol of imperialism. Because Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow was the sour turning point in the Napoleonic Wars, this symbol is loaded with irony. Like the majority of the objects in the image, the flag and the eagle are stuck in the snow: imperialism has failed.

The governor of Moscow, Fyodor Rostopchin, ordered the city to be burned by convicts after the Russians defeated the French in order to ensure that the French did not seize it. He also hoped that the French who remained would be forced to fight fire and criminals. Another problem soon arose, for the areas that were not damaged were quarrelled over by the soldiers. Fortunately for the French, food and alcohol were not the only goods left in the city; weaponry was also left behind (R. Asprey, Rise and Fall 337).

The function of this image is to satirize Napoleon and his troops’ departure from Moscow. Its purpose is to incite humor, which is effected by the men’s entrapment in the snow. Additionally, its function is to portray Napoleon as a greedy and selfish leader, as he is safe and warm inside a tent.

“Following naturally from the Romantic fascination with the old and exotic was an attraction to the supernatural, bizarre, or nightmarish” (N. King, Romantics 10). Being trapped in the snow, as the soldiers in the image are, is precisely that: nightmarish. Again, the sublime is a driving force in this image; however, terror is the predominant emotion it invokes. Birds are lurking above the men and the viewer can only see grayness in the distance. Although it was believed during the Romantic period that “to be alone in wild, lonely places was for the Romantics to be near to heaven,” this scene is far from the divine (N. King, Romantics 8).

Locations Description

To Alexander I, Moscow was only the “holy” capital; St. Petersburg was the empire’s capital. While the city was set ablaze, Napoleon safely waited in the Kremlin, the city’s citadel (S. Englund, Napoleon: A Political Life 377).

Publisher

Thomas Tegg

Collection

Accession Number

CA 8938

Additional Information

Bibliography

Asprey, Robert. The Rise and Fall of Napoleon Bonaparte. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

Combe, William. The Life of Napoleon: A Hudibrastic Poem in Fifteen Cantos. London: T. Tegg III, 1815.

Englund, Steven. Napoleon: A Political Life. New York: Scribner, 2004.

Herold, C. The Age of Napoleon. New York: American Heritage Publishing Co., 1963.

King, Neil. The Romantics: English literature in its historical, cultural, and social contexts. New York: Facts on File, Inc., 2003.