Exhibit

Creation Date

1829

Height

5 cm

Width

8 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

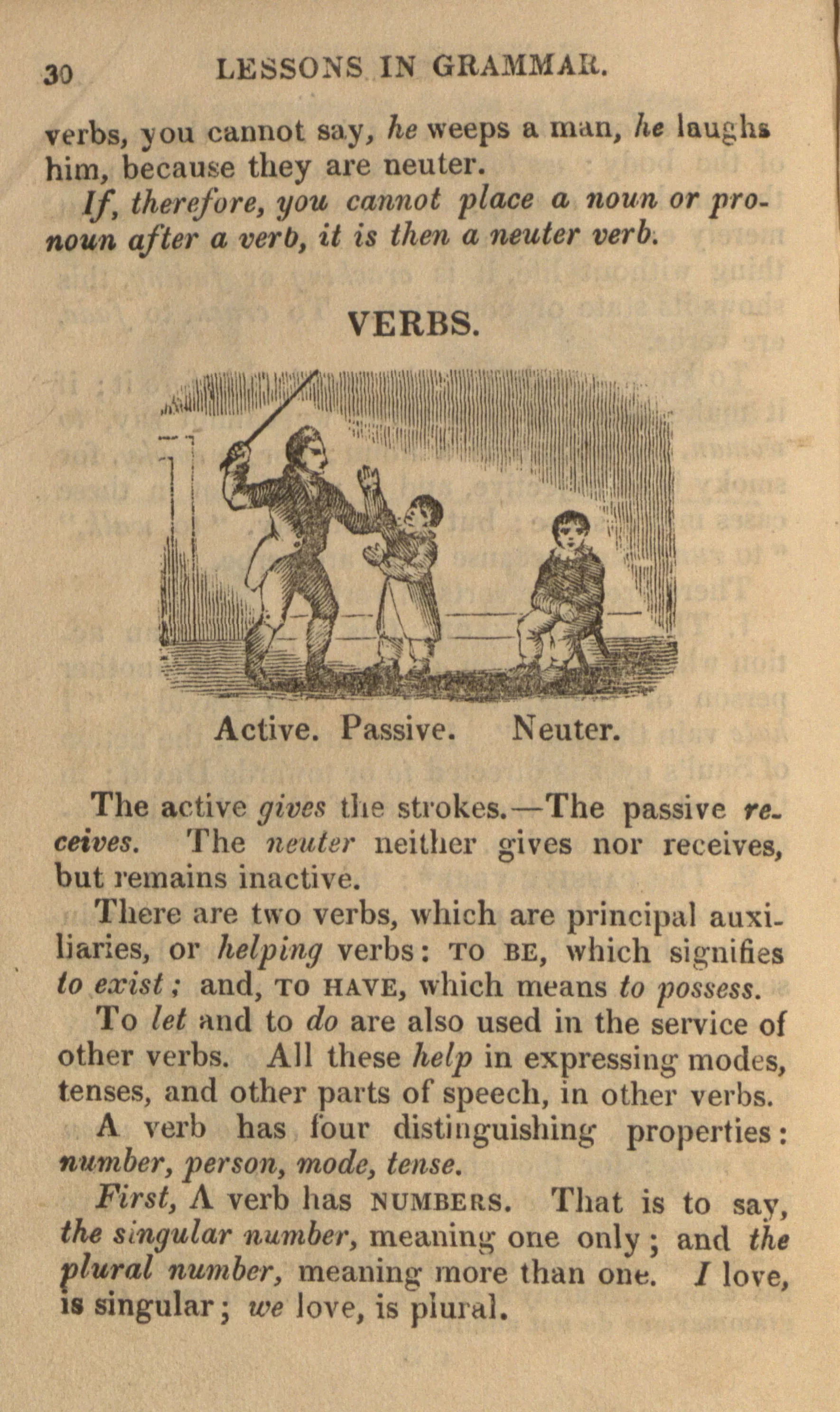

This image serves to visually illustrate and explicate a lesson plan in a grammar book. The accompanying text appears to be a lesson plan regarding verbs and their "properties." The image depicts three figures, each of which represents a different "voice" of verbs.

The image is set in what appears to be a schoolroom. The master holds a stick above his head, preparing to give "strokes" to the young boy he grips by the elbow. The boy, dressed in a long coat and pants, looks up at the master. To their right, another boy sits in a chair, looking out in the direction of the viewer. The master is labeled "Active," the boy he intends to hit, "Passive," and the seated student, "Neuter"; the image's title, "Verbs," appears in capital letters above the scene.

Sarah Trimmer’s influential periodical, The Guardian of Education, was first published in 1802, with its last edition published in 1806. Like many of her contemporaries, Trimmer was firmly against Rousseau’s educational philosophies, believing that it was essential for children to be taught moral and religious values by properly trained adults. The Guardian’s reviews reflected this position, but they also reflected her push for the use of images in instructional contexts (Kinnell 50).

Though nearly all educational philosophies of the time encouraged the use of images in some context, not all agreed that the information associated with them should be conveyed solely by adults. Andrew Bell’s monitor system, which was first used in London in 1789, advocated the use of brighter students as tutors for their peers, with several adult “monitors” to ensure that things proceeded smoothly. Furthermore, though Bell’s system did allow a use of the visual, his strict rejection of physical punishment would have rendered this particular image unsuitable (Blackie).

Joseph Lancaster developed a similar system independently. Lancaster’s system differed from Bell’s, however, in its use of three student monitors rather than one—one to teach, one to maintain discipline, and one to inspect, with all three answerable to an adult monitor. Lancaster also did not share Bell’s rejection of humiliation as punishment, freely assigning punishments when he felt they were due (Doheny 329).

Images in children’s textbooks of the period were intended to provide students with an example of the concept or subject being addressed.

Ingram Cobbin’s illustration demonstrates the way in which visual methods were being used to fix multiple ideas in children’s minds; while the stern content of the image was not explicitly referenced in their theories, both Locke and Rousseau approved the notion of engaging the visual in pedagogical practices. While Locke advocated a merging of instruction with entertainment, and Rousseau believed that instruction should be direct and unadulterated, both agreed that images had the potential power to make a deeper impression on children than texts (Ferguson 217; Bator 54).

This image also shows the continued partnership between visual pedagogy and associationism. In its most basic form, associationism “offers intimations of the viewer's close coupling of simplified forms to the complex material and immaterial experiences they conjure up" (Stafford 319). Many children’s authors, William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft among them, followed Locke’s example by embracing the theory’s relevance to education (Ruwe 5). Though this image would, according to that theory, provide a mental association between the verb forms and their appropriate subjects, it would also form a negative association between learning and physical punishment, a practice Locke was against.

Collection

Accession Number

CA 9566

Bibliography

Bator, Robert. “Out of the Ordinary Road: John Locke and English Juvenile Fiction in the Eighteenth Century.” Children’s Literature 1 (1973): 46-53. Print.

Blackie, Jane. “Bell, Andrew (1753–1832).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Web. 1 May 2009.

Doheny, John. “Bureaucracy and the Education of the Poor in Nineteenth Century Britain.” British Journal of Educational Studies 39.3 (1991): 325-39. Print.

Ferguson, Frances. “The Afterlife of the Romantic Child: Kant and Rousseau Meet Deleuze and Guattari.” South Atlantic Quarterly 10.1 (2003). Print.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Emile. Trans. Barbara Foxley. London: Tuttle Publishers, 1993. Print.

Ruwe, Donelle. "Guarding the British Bible from Rousseau: Sarah Trimmer, William Godwin, and the Pedagogical Periodical." Children's Literature 29 (2001): 1-17. Print.

Schnorrenberg, Barbara Brandon. “Trimmer, Sarah (1741–1810).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Web. 1 May 2009.

Stafford, Barbara. “Romantic Systematics and the Genealogy of Thought: The Formal Roots of a Cognitive History of Images.” Configurations 12.3 (2004): 315-48. Print.