Creation Date

16 November 1807

Height

40 cm

Width

31 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

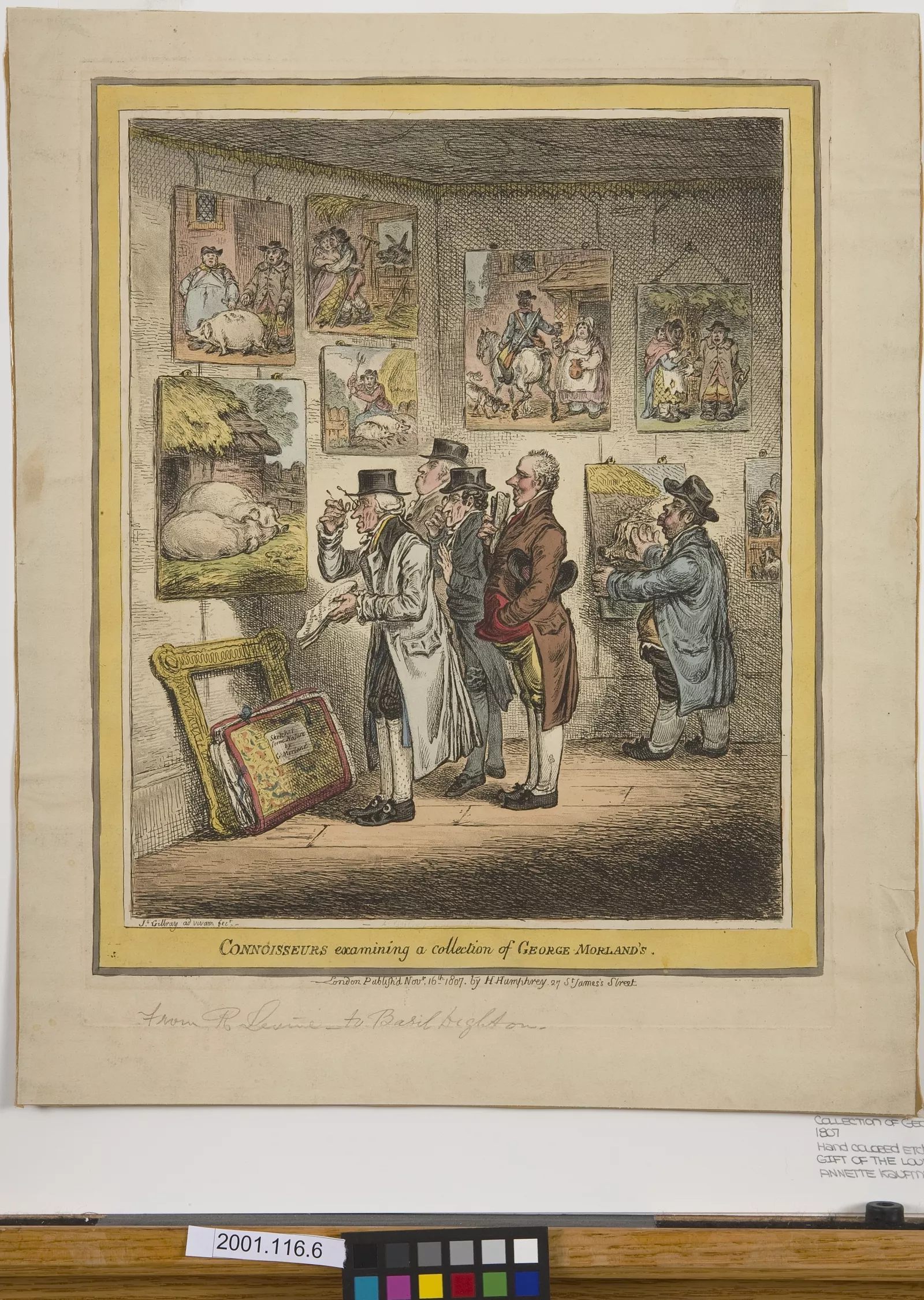

In this print, a group of connoisseurs examines several paintings. Given that these paintings depict rural subjects, a topic of which the connoisseurs can have little knowledge, the print questions the competency of these professed experts and so satirizes the role of the connoisseur. This satire is furthered by the unappealing renderings of the paintings; their grossness, together with the fact that this was considered "popular" art of the period, suggests that the connoisseurs are being led by public opinion rather than refining it.

In the corner of a room, five men examine the paintings hung on the two visible walls. On the right, a coarse figure identified at Mr. Mortimer, an art dealer and restorer, spits on one of the paintings and rubs it with his hand. The other four men are identified as well-known connoisseurs. The figure on the left, either Captain Baillie or J.J. Angerstein, holds a pamphlet with the words “Catalog of Pictures by Morl . . .” on the cover; with his right hand, he peers through a pair of eyeglasses held upside down. The figure in the middle also holds a glass up to his eye, while the right-most figure in the group holds a paper on which can be read “Pigs.” The connoisseurs appear to range from middle to old age; they are dressed well, but sloppily. The paintings on the walls satirize the rural scenes of George Morland, depicting grossly fat butchers, farmers, and women; raggedly dressed, rural inhabitants engaged in cruel or licentious behavior; and ignoble farm animals. The paintings are unframed, though one large gilt frame leans against the wall at the connoisseurs’ feet. In front of this frame is a portfolio bulging with papers and labeled “Sketches from Nature by G. Morland,” which may refer to Morland’s practice of reproducing his sketchbooks in volumes of etchings that were sold to the public.

This print depicts the practice of viewing art in dealers’ galleries, which arose in London in the eighteenth century. At this time collecting art became more popular with the middle classes, and the art market expanded considerably, as is evidenced by the establishment of auction houses in mid-eighteenth century London and the regular sale of artworks at auctions. In the nineteenth century both private and institutional collecting increased and dealers' galleries multiplied. Viewing art in privately owned (and many publicly owned) galleries was usually a commercial experience, as the works were for sale and because viewers often had to pay a fee to enter the gallery. Consequently, the increase in dealers' galleries is one example of the commercialization of visual culture in the Romantic period, and is evocative of the shift from a system of private art patronage to a public art market.

The humor of this print lies chiefly in the pictures depicted on the walls, whose subjects parody the rural genre scenes for which Morland was most famous. These paintings of unattractive farm animals and laborers are comically inappropriate objects of interest for the so-called connoisseurs. As well-dressed gentlemen in the urban setting of a commercial art gallery, it seems unlikely that they possess an expert's knowledge of the rural scenes before them; furthermore, their catalogs and eyeglasses suggest that undue interest is being paid to these scenes of relentlessly everyday life. Because the connoisseurs’ interest does not seem warranted by the paintings themselves, the print suggests that it has instead been sparked by the popularity of Morland’s work in a growing art market. It is fitting, then, that the gaze of the connoisseurs seems to be directed by the commercial figure of the art dealer on the right, whose crassness equals that of the paintings he sells. Although the source of a connoisseur’s knowledge and pleasure is his gaze—a comparative gaze that evaluates the works before him in relation to those produced by the same artist or school—the connoisseurs in this print are figuratively blind: they are insensitive to the inappropriate oddity of such coarse rural scenes being used as signs of refinement for the urban art consumer.

This print also speaks to the tensions developing between the private and public roles of art during the Romantic period. Though it failed to meet the standards for public art set by the Royal Academy and exemplified by history painting and grand manner portraiture, connoisseurs were known for promoting Dutch genre painting, preferring the private content and intimate pleasures of the rural or mundane scene. The esoteric opinions of the connoisseurs still managed to occasionally influence public opinion, however, as when J.J. Angerstein extolled the early work of David Wilkie. His favorable comments were soon repeated by critics in the public press and helped contribute to the enormous popularity of Wilkie’s work at the Royal Academy exhibition (Solkin). In contrast, this print emphasizes the potential for herd mentality and hypocrisy among the connoisseurs as a group, suggesting that they are influenced as much by the popular taste of their peers as by their own educated sensibilities. Furthermore, by depicting the social act of viewing art in a private gallery, this print operates as a dialectic between public and private aesthetics. The rural scenes on view exemplify a more popular genre of painting, but they are still oil paintings and would have been considered cabinet pictures: appropriate for hanging in the semi-public or informal areas of a house, or even in the main reception rooms of smaller bourgeois townhouses. However, the paintings are also being represented here in a satirical print that would have been exhibited, not on the wall, but in cradles or portfolios kept in private cabinets, libraries, and informal living areas, easily accessible for casual viewing by individuals or intimate groups. And yet, a print such as this one could have hung in the window of a print shop or in a gallery like that which is depicted, viewed for commercial purposes and circulated as an object in the very practices being satirized. Consequently, the print asserts that supposedly private aesthetic tastes are both socially constituted and publicly displayed, while also representing relatively public artworks and viewing practices in a less formal and arguably more private form.

Locations Description

This scene is presumably set in the commercial gallery of Mr. Mortimer, an art dealer and restorer portrayed on the right, during a temporary exhibition of George Morland’s work. Several commercial art galleries of the time were devoted to Morland's pieces. In 1792, the dealer Daniel Orme opened an extremely successful Morland Gallery in Bond Street, London, with over one hundred of Morland’s works on sale. Around 1793 Mr. Smith also opened a temporary Morland Gallery in London, issuing a catalog of 36 paintings that he planned to reproduce in engravings and publish by subscription (Belsey and Rosenthal).

Publisher

Hannah Humphrey

Collection

Accession Number

2001.116.6

Additional Information

Bibliography

Allen, Brian. Towards a Modern Art World. New Haven: Yale UP, 1995. Print. Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

Allan, D. G. C.. “Whitefoord, Caleb (1734–1810).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Online ed. Ed. Lawrence Goldman. Jan. 2008. Web. 19 Aug. 2013.

Barrell, John. The Birth of Pandora and the Division of Knowledge. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1992. Print. New Cultural Studies Series.

---. The Dark Side of the Landscape: the Rural Poor in English Painting, 1730-1840. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1980. Print.

Belsey, Hugh and Michael Rosenthal. "Morland." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford UP. Web. 19 Aug. 2013.

Bermingham, Ann. Landscape and Ideology: The English Rustic Tradition, 1740-1860. Berkeley: U of California P, 1986. Print.

---. “The Aesthetics of Ignorance: The Accomplished Woman in the Culture of Connoisseurship.” Oxford Art Journal 16.2 (1993): 3-20. Print.

Brewer, John. “ ‘The Most Polite Age and the Most Vicious:' Attitudes Towards Culture as a Commodity, 1660-1800.” Consumption of Culture, 1600-1800: Image, Object, Text. Ed. Ann Bermingham and John Brewer. New York: Routledge, 1995. Print.

---. The Pleasures of the Imagination: English Culture in the Eighteenth Century. London: Farrar, 1997. 252-87. Print.

Brown, David Blayney. "Angerstein, John Julius." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford UP. Web. 19 Aug. 2013.

“connoisseur, n.” Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. OED Online. June 2013. Oxford UP. 19 Aug. 2013.

Clark, Michael and Nicholas Penny. The Arrogant Connoisseur: Richard Payne Knight, 1751-1824. Exhibition Catalogue. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1982. Print.

George, M. Dorothy. Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires in the British Museum. Vol. 9. London: by order of the Trustees, 1949. 570-71. Print.

Hemingway, Andrew. Landscape Imagery and Urban Culture in Early-Nineteenth Century Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1992. Print.

Lippincott, Louise. Selling Art in Georgian London: The Rise of Arthur Pond. New Haven: Yale UP, 1983. Print.

Miller, Elizabeth. "Baillie, William." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford UP. Web. 19 Aug. 2013.

Mount, Harry. The Reception of Dutch Genre Painting in England, 1695-1829. Diss. Cambridge University, 1991. Print.

Pears, Ian. The Discovery of Painting: The Growth of Interest in the Arts in England, 1680-1768. New Haven: Yale UP, 1988. Print.

Solkin, David H. “Crowds and Connoisseurs: Looking at Genre Painting at Somerset House.” Art on the line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780-1836 Ed. Solkin. New Haven: Yale UP, 2001. 157-71. Print. The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

---. Painting for Money: The Visual Arts and the Public Sphere in Eighteenth-Century England. New Haven: Yale UP, 1993. Print. The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

Waterfield, Giles, et al. Palaces of Art: Art Galleries in Britain, 1790-1990. London: Dulwich Picture Gallery, 1991. Print.