Creation Date

November 1818

Height

24 cm

Width

32 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

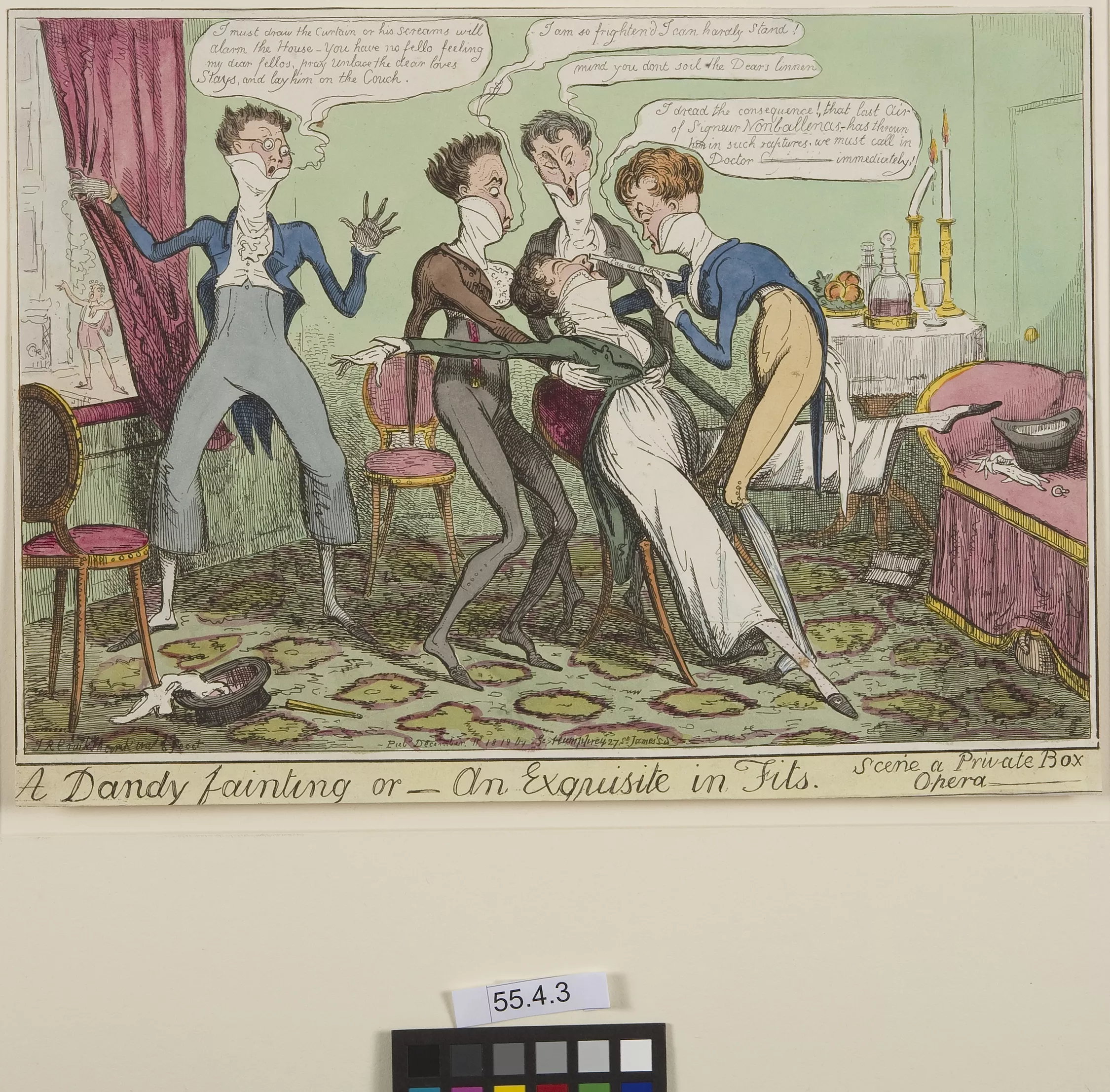

This print depicts a dandy, emotionally overcome by the performance of a castrato opera singer, fainting in the company of his friends, four other dandies. The piece satirizes the effeminacy and performed exaggerations of the "dandy" as a type, and strengthens associations between the pursuit of fashion, the cultivation of art and aesthetic experience, and femininity or transgressive sexuality.

A dandy has fainted and leans back in a chair with his limbs straight out, while three other dandies support him and a fourth closes a curtain. Beyond the curtain we can see a castrato opera singer gesturing and performing on stage, as well as some of the other boxes. The dandy closing the curtain says, “I must draw the curtain or his screams will alarm the House—you have no fello feeling my dear fellos, pray unlace the dear loves Stays, and lay him on the Couch.” Two of the supporters say, “I am so frighten’d I can hardly stand!” and, “Mind you don’t soil the Dear’s linen.” The third supporter holds a bottle of “Eau de Cologne” to the fainter’s nostrils and says, “I dread the consequence! that last Air of Signeur Nonballenas has thrown him in such raptures, we must call a Doctor—immediately!” The opera box is strewn with hats, gloves, white silk scarves, and a fan. A chamber pot is visible beneath the couch. On the table are peaches, a decanter of wine, an empty decanter, two glasses, and two candles, one of which dips towards the other.

This print connects dandies to artistic commodification, effeminacy, and homosexual desire. The dandies are men who value art, both the performing arts and the sartorial arts of their own persons. The conflation of the dandy and the opera-lover in this print suggests that dandies not only use fashion to create themselves as works of art, but that they also liken themselves to the artists they admire on stage. This is most pronounced in the dandy on the left, whose gesturing arms and widespread hand mirror the pose of the opera singer. Yet the opera singer is not a typical performing artist; he is a castrato, a eunuch who represents effeminate and enfeebled masculinity at its height. The castrato is both a monstrous form of masculinity—associated with luxury, enervation, and sodomy—and a highly sought after commodity whose voice is a prized rarity (Nussbaum 34-5). By modeling himself after the castrato, the dandy similarly becomes an exceptional commodity that is both prized for its artistry and denigrated for its anomaly.

This print’s emphasis on dandies as a group whose admiration for the castrato is taken to the extreme counters the dominant interpretation of the dandy as an excessively autonomous and stoic individual, a figure who makes himself an artwork so successfully that he can be neither imitated nor commodified (Garelick). This print depicts dandies not as self-created, idiosyncratic individuals, but as a social unit formed from a shared desire for artistic commodities. A homogenous group of opera lovers, these dandies display many of the characteristics associated with London’s sodomite sub-cultures, such as effeminacy, secrecy, and hyper-sexuality (Trumbach). Each dandy is feminized by both his hysterical behavior and his sartorial appearance. Their cinched waists, the high waistlines of their pants and jackets, and their exaggerated chests liken them to contemporary women in empire-waist dresses, while the fan on the floor in the foreground is also a highly feminized accessory. As the text emphasizes, it is the performance of a castrato opera singer, aptly named “Signeur Nonballenas,” who has thrown one of the dandies into “raptures,” a word that conjures sexual ecstasy, and has caused him to faint. The other dandies also refer to the fainter with terms of endearment, such as “dear” and “love,” while the three dandies who support the fainter stand between his legs and grasp his chest. Like the opera singer, each dandy is both male (a “Signeur”) and emasculated (“Nonballenas”), representing homosexual desire as a contradiction. The two candles on the table also register as phallic symbols, one phallus leaning towards the other, while the chamber pot under the couch alludes to bodily functions. Finally, the closing of the curtain signals that this opera box in the public theater is about to become a private space, one in which illicit activity could occur unseen.

Locations Description

The action depicted in this print takes place in a private opera box, reserved for those patrons who bought subscription tickets to the entire season. Each box was consequently associated with a particular person or family, and Opera-box directories, books specifying which boxes had been taken by which subscribers, were published at the beginning of each season. Although these boxes were a part of public theaters, they could be quite luxurious, quasi-domestic spaces, as depicted here: the box includes a carpet, a sofa, a table laid with food and drink, chairs, and a curtain that can be closed to ensure privacy.

Publisher

G. Humphrey

Collection

Accession Number

55.4.3

Additional Information

Bibliography:

Burnett, T.A.J. The Rise and Fall of the Regency Dandy: The Life and Times of Scrope Berdmore Davies. London: John Murray, 1981. Print.

Campbell, Colin. The Romantic Ethic and the Spirit of Modern Consumerism. Oxford: Blackwell, 1987. Print.

“dandy, n.1 (and a.).” The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. OED Online. June 2013. Oxford UP. 19 August 2013.

“dandy, dandi, n.3.” The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. OED Online. June 2013. Oxford UP. 19 August 2013.

Donald, Diana. Followers of Fashion: Graphic Satires from the Georgian Period. Exhibition Catalogue. London: Hayward Gallery, 2002. Print.

Garelick, Rhonda K. Rising Star: Dandyism, Gender, and Performance in the Fin de Siècle. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1998. Print.

George, M. Dorothy. Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires in the British Museum. Vol. 9. London: by order of the Trustees, 1949. 846-47. Print.

Koestenbaum, Wayne. The Queen’s Throat: Opera, Homosexuality and the Mystery of Desire. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993. Print.

Kowaleski-Wallace, Beth. “Shunning the Bearded Kiss: Castrati and the Definition of Female Sexuality.” Prose Studies 15.2 (1992): 153-70. Print.

Moers, Ellen. The Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm. London: Secker and Warburg, 1960. Print.

Nussbaum, Felicity A. The Limits of the Human: Fictions of Anomaly, Race, and Gender in the Long Eighteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

Nobel, Yvonne. “Castrati, Balzac, and Barthes’ S/Z.” Comparative Drama 31.1 (1997/1998): 28-41. Print.

“opera, n.1.” Oxford English Dictionary. March 2009. OED Online. 5 April 2009.

Peschel, Enid and Richard. “The Castrati in Opera.” Opera Quarterly 4.4 ( 1986-87): 21-38. Print.

Shapiro, Susan C. “ 'Yon Plumed Dandebrat': Male ‘Effeminacy’ in English Satire and Criticism.” RES 39.155 (1988): 400-12. Print.

Stanton, Domna C. The Aristocrat as Art: A Study of the Honnete Homme and the Dandy in Seventeenth- and Nineteenth-Century French Literature. New York: Columbia UP, 1980. Print.

Trumbach, Randolph. “London Sodomites: Homosexual Behaviour and Western Culture in the 18th Century.” Journal of Social History 11.1 (1977): 1-33. Print.