Creation Date

1782

Height

11 cm

Width

17 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

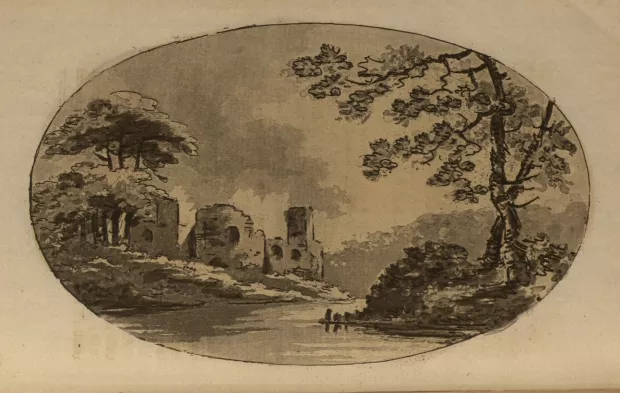

Grand Woody Banks near Ross-on-Wye was originally sketched in the travel journal of William Gilpin. This and other sketches were eventually published in the printed version of Gilpin’s journal. Gilpin first made the journey down the Wye in 1770, but his book was not published until 1782, due in large part to his resistance to publishers’ inability to accurately recreate the watercolor-and-wash sketches Gilpin made in his original travel journal (Andrews, In Search of the Picturesque 86). In the first published edition of Gilpin’s Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales, etc. Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; Made in the Summer of the Year 1770, the sketches were reproduced by an unusual combination of etching and aquatint techniques. However, starting with the publication of the second edition in 1789, only aquatinting was used. This recreation is an aquatint.

During the Romantic period in England, Gilpin helped popularize picturesque tourism—that is, sightseeing centered on experiencing the Romantic notion of the picturesque: a natural object, like a stone, tree, etc., that stood out in stark contrast to its surroundings and often impressed the viewer with a feeling of the sublime. In this work, picturesque elements can be recognized in the organization of nature and vegetation, as well as the juxtaposition of the human world (the ruins) and the natural world (the trees overrunning the ruins). Hints of the sublime also can be found in the nebulous border between the distant wooded banks and the horizon. As is typical of picturesque landscape drawing, there is no effort made to represent the landscape accurately; instead, Gilpin was more concerned with creating harmonious drawings that incorporated elements of the picturesque and sublime. For example, it is likely that Gilpin invented the ruins near the center of the sketch in order to embellish the landscape, and it is probable that he removed any trees, shrubbery, etc. that he found unsightly. Consequently, Gilpin used his sketches to convey to readers what he saw as reinvented by his own mind, and to encourage them to pursue similar views. However, the boatmen that acted as de facto tour guides on the Wye scoffed at Gilpin’s (mis)representations, and advised tourists familiar with Gilpin’s guidebook not to bother looking for the scenes “recreated" there since they did not, in fact, exist (William Mason, qtd. in Barbier 71). "Grand Woody Bank near Ross-on-Wye," an aquatint recreation of a sketch in Gilpin's travel journal, illustrates Gilpin's editing of natural scenery and serves as an example of a "picturesque" landscape. This was one of the first scenes a tourist witnessed on the Wye Tour.

Robert Bloomfield, famous for his semi-autobiographical poem The Farmer’s Boy (1800), took a ten day tour of the Wye Valley during a period in his life marked by personal and professional turmoil. The tour rejuvenated him, and the versification of his travel journal eventually became The Banks of Wye: a Poem in Four Books (Kaloustian). The poem is primarily significant for two reasons. First, and most obviously, it addresses the scenery and spectacles of the Wye Tour, giving the reader a good idea of what to expect on such a tour. Second, it follows the decidedly Wordsworthian example of examining the effects of that scenery on the self. Passages like the following endow the scenery with the ability to affect humans:

Till bold, impressive, and sublime,

Gleam’d all that’s left by storms and time

Of GOODRICH TOWERS. The mould’ring pile

Tells noble truths,—but dies the while.

(Bloomfield 1.149-52)

Note how the ruins of Goodrich Castle are capable of telling “noble truths,” a direct interaction that Gilpin et alia would have either not noticed or summarily dismissed. Other passages focusing on the direct effect of natural images on the viewer include the following:

Then CHEPSTOW’S ruin’d fortress caught

The mind’s collected store of thought,

A dark, majestic, jealous frown

Hung on his brow, and warn’d us down.

(Bloomfield 2.315-18)

and

TINTERN, thy name shall hence sustain

A thousand raptures in my brain;

Joys, full of soul, all strength, all eye,

That cannot fade, that cannot die.

(Bloomfield 2.131-34)

The first of these passages features not only personification of Chepstow Castle, but also describes the ruins’ ability to catch “the mind’s collected store of thought,” as well as its capacity to “warn” viewers. This warning is likely related to mortality, given the nearby mention of the “setting sun” (Bloomfield 2.313), a typical symbol of waning life. The second passage also utilizes one of the Wye Tour’s most famous spectacles (Tintern Abbey) to illustrate scenery’s ability to influence the viewer. The mere name of the Abbey is enough to call to the poet’s mind “a thousand raptures,” some of which included “priest[s] or king[s]” (2.124), “some BLOOD-STAIN’D warrior’s ghost” (2.125), or “grass-grown mansions of the dead” (2.114). The capacity of Nature to wreak such significant alterations in a viewer’s psyche runs diametrically opposed to the strictly evaluative eye of the picturesque tourist, and embodies a decidedly post-“Lines” worldview.

The popularity of the Wye Tour, a picturesque tour through the England-Wales border down the River Wye, increased exponentially during the 1780s and the decades that followed (though the Wye river was a popular site for at least twenty-five years before Gilpin’s tour); this was due in large part to the tour guide-book Observations on the River Wye, written by the Reverend William Gilpin and published in 1782. The tour focused on the natural beauty of the Wye Valley, especially the part of the Valley that fit Gilpin’s idea of the “correctly picturesque”—usually characterized by a natural object (e.g., a tree, a stone, cliffs; anything not human-made) which stood out in stark contrast to its surroundings and was often in close proximity to people or human-made objects (factories, bridges, and the like). The tour lasted two to three days by boat (the most common form of travel for tourists) or carriage (used only by the very wealthy), and significantly longer by foot; William Wordsworth and his sister, Dorothy, took a walking tour of the Wye Valley in 1798 (see William Wordsworth’s memorial poem “Lines composed a few miles above Tintern Abbey on Revisiting the banks of the Wye Valley during a tour, July 13, 1798”). The most common form of travel was by pleasure boat, which featured a canopy to shield tourists from the wind, sun, and rain; a handful of tables for writing or drawing; and several oarsmen who acted as de facto tour guides and cost three to four guineas for two days' employment (Moir 125). The tour extended, as Gilpin noted, “To [Chepstow] from Ross, which is a course of near 40 miles” and featured “a succession of the most picturesque scenes” (Gilpin 7). Highlights included Ross-on-Wye, Goodrich Castle, Symond’s Yat, Monmouth, Tintern Abbey, Piercefield, Chepstow Castle, and, finally, the junction of the Rivers Wye and Severn at Chepstow.

Picturesque tourism as an industry was largely popularized by the publication of Gilpin’s Observations on the River Wye in 1782. Tourists of the "picturesque" traveled to Scotland, North and South Wales, the Wye Valley, and the Lake District (in northwest England) in search of scenery manifesting this ideal. Oftentimes, tourists brought watercolors to quickly paint or sketch the scenes that most captivated them, in the fashion of Gilpin. These tourists, and their dogged pursuit of the picturesque, would later be lampooned by caricaturists in the early years of the 1800s, but picturesque tourism maintained significant popularity until the mid-nineteenth century.

Associated Works

Locations Description

The Wye River

The Wye River rises on Plynlimon Mountain in Wales and flows southeast for 130 miles. The last forty miles of the river, beginning at Ross-on-Wye, made up the Wye Tour during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Gilpin described its beauty as related primarily to its “mazy course” and “lofty banks” (Gilpin 7). The river winds along the English-Welsh border until it empties into the River Severn at Chepstow, and features the ruins of several castles, abbeys, and the like along its banks.

Ross-on-Wye

The launching point for the Wye Tour, Ross-on-Wye, was not a large town during the latter part of the eighteenth century. However, it was famous as the hometown of the philanthropist John Kyrle (Andrews, In Search of the Picturesque 90). Its fame grew exponentially when picturesque tourism was in vogue. At the peak of the Wye Tour’s popularity, there were eight to ten pleasure boats that ferried passengers between Ross and Chepstow during the summer months. Picturesque tourists would arrange their own transportation to Ross, perhaps stay the night, and then set out for Chepstow the following morning, taking special note of the beautiful forests and hills just a few minutes downriver from Ross (Andrews, In Search of the Picturesque 89).

Copyright

Copyright 2009, Department of Special Collections, Memorial Library, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI

Collection

Accession Number

RPZN G42 W Cutter

Additional Information

Andrews, Malcolm. “Gilpin, William (1724–1804).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Ed. Lawrence Goldman. Oxford: OUP, 2004. 28 Mar. 2009.

---. In Search of the Picturesque. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1989. Print.

Barbier, C.P. William Gilpin. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1963. Print.

Bloomfield, Robert. The Banks of Wye: a Poem. In Four Books. London, 1811. Print.

Gilpin, William. Observations on the River Wye. 1782. Oxford: Woodstock Books, 1991. Print. Revolution and Romanticism, 1789-1834.

Kaloustian, David. “Bloomfield, Robert (1766–1823).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Ed. Lawrence Goldman. Oxford: OUP, 2004. 21 Aug. 2013.

Michasiw, Kim I. "Nine Revisionist Theses on the Picturesque." Representations 38 (1992): 76-100. Print.

Moir, Esther. The Discovery of Britain; The English Tourists. London: Routledge & K. Paul, 1964. Print.