Exhibit

Creation Date

1836

Medium

Genre

Description

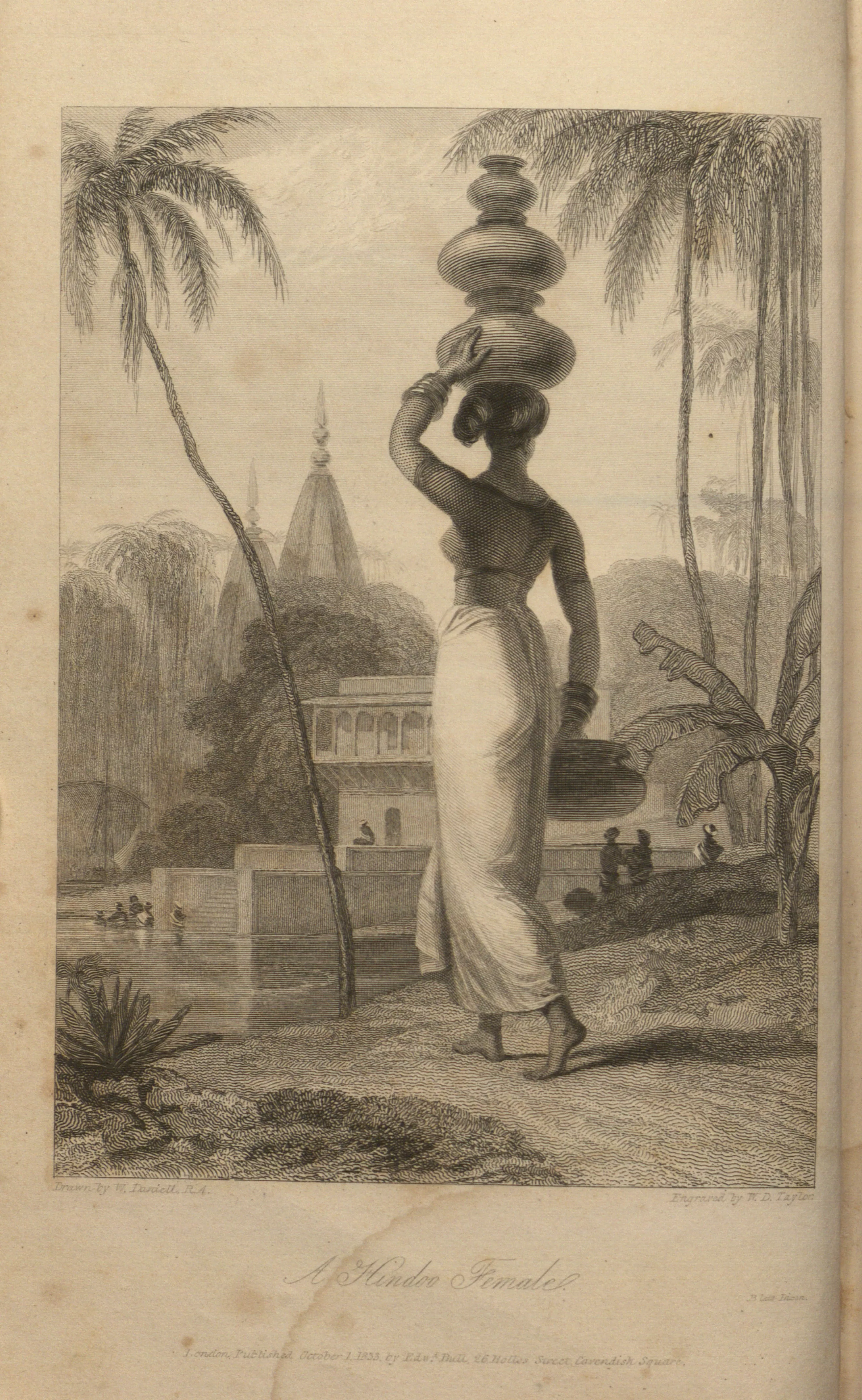

In this engraving, which depicts a woman in relief against distant temple spires, William Daniell combines techniques of the picturesque with elements of erotic Indian art to produce an image that is at once a site of the sacred and of the profane.

A native “Hindoo” woman is portrayed carrying three pots of water on her head as she descends down to the river. The viewer is presented with a voyeuristic gaze of her backside; the implied motion of her figure is graceful and seductive. The foreground is composed of a path covered with lush plants, and a single palm tree juts up from the ground, mimicking the voluptuous curves of the woman’s body. The middle ground contains a white walled temple that opens onto a sacred bathing area. Just behind this temple are two temple peaks that emerge like mountains behind the dense foliage. Consequently, this image juxtaposes the profane, seductive woman with sacred space (the temples). This trope is a common one employed in native Indian painting, sculpture, and architecture.

The Oriental Annual, or Scenes in India constituted a combination of fictional and instructional manuals that were widely distributed and read; many book reviews regarding The Oriental Annual are found in periodicals of the time.

At the age of fourteen, William Daniell accompanied his uncle Thomas Daniell, a landscape painter trained at the Royal Academy, on a journey to India from 1786 to 1794. The first two years were spent in Calcutta preparing Views of Calcutta. After the first two years they traveled to the Punjab Hills and then back to Calcutta in 1971. They began a second tour in 1792, working their way through Mysore and Madras. After staying in Madras from 1793 to 1794 they finally returned to England. Drawings made during these trips were engraved in books and prints (some of which were exhibited at the Royal Academy).

The Daniells arrived in India during a period of political transition, just after the departure of Warren Hastings and prior to the instatement of Charles Cornwallis (1738-1805), the new Governor-General of India. Cornwallis was the first Governor-General appointed under the new India Act of 1784 (passed during William Pitt's term as British prime minister). The act was passed in part as a means of reigning in the Hastings style of government, which was seen as “too indigenous, free-wheeling and popular, too benevolent and multi-national and not British enough” (De Almeida 168). Hastings became known for incorporating native Indians as administrators, financers, and civil servants. The India Act proceeded to centralize Company administration: a six-member Board of Control was created which controlled the Company’s possessions abroad, and the Governor-Generalship was made a Crown appointment with full control over other governors and presidencies in India. Additionally, the act created a centralized British military in India.

Charles Cornwallis (1738-1805) gained experience in the military while serving in America, and was employed to carry out England’s imperialist vision in India. His strategic military victories on land (for example, in Mysore with Tipu Sultan) not only extended England's rule, but also provided sepoys that could be recruited and kept on reserve for the Napoleonic Wars. Additionally, Cornwallis’ belief that “every native of Hindoostan is corrupt” gave way to a purging of Indian natives from administrative positions and forbid mixing or socializing between races. A purification and segregation process, in which hybridity was especially scorned, took place under Cornwallis’s rule (De Almeida 168). Dalrymple claims that “these new racial attitudes affected all aspects of relations between the British and Indians” (Dalrymple 41). Prior to Cornwallis’s strict racial segregation, many British officials were integrated into Indian society by learning the language, adopting Indian dress and mannerisms, and marrying Indian women (bibis). The decline of this integration became apparent with the declining rates of bibis on wills; by the mid-nineteenth century no records of bibis on wills exist (Dalrymple 1). Even though these changes brought about tension between the British and Indians, many British officials continued to be patrons of Indian art (Archer 1-15).

The Daniells were trained in the picturesque, which

. . . emphasized the composition of the painting in terms of the three areas which were of concern in planning a garden prospect: the ‘foreground’, which ought to include arresting, natural features or artifacts or figures of people or animals; the ‘middle ground’, which was supposed to depict the main subject of interest of an architectural subject, a house or monument; and the ‘background’ which was suppose to represent the distant setting of forest, hills, or mountains against the sky. (De Almeida 168)

In A Hindoo Female, the female body initially becomes the site of interest on account of its size, which, relative to the surrounding space, is significantly large. Grounded in this primary impression, the human figure becomes a substitute for the architectural form, performing a structural presence of intense beauty that taunts a desire of possession.

A Hindoo Female and subsequent engravings that were produced by the Daniells were widely circulated in England, and they fed the English imagination with ideas of the beautiful and exotic to be found in India. The picturesque, in turn, was affected by its contact with Indian artistic traditions. Even though William Daniell does not mention his familiarity with this erotic Indian female, his sketches in 1792 of the voluptuous, bare breasted women on the façade of the temple Karli attest to his encounter with erotic Indian sculptures (Archer 144). The voluptuous, erotic women depicted on many Indian temples most likely inspired the seductive qualities of the women in the Daniells' engravings.

Locations Description

The East India Company was formed to trade with East and Southeast Asia and India and was instituted by royal charter on Dec. 31, 1600. Although it started as a monopolistic trading company, it soon became involved in politics and acted as an instrument of British imperialism in India from the early eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth century. The company was founded with the hope of dominating the East Indian spice trade. This trade had been a monopoly of Spain and Portugal until the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 gave England the opportunity to appropriate the lucrative market.

Publisher

Bull and Churton (or Bull and Co)

Accession Number

AY 13 O7 1834

Additional Information

Bibliography

Archer, Mildred. Early Views of India: The Picturesque Journeys of Thomas and William Daniell, 1786-1794: The Complete Aquatints. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1980. Print.

Daniell, William and Hobart Caunter. The Oriental Annual, or Scenes in India. Vol. 3. London, 1836. Print. 7 vols. 1834-40.

De Almeida, Hermione and George H. Gilpin. Indian Renaissance: British Romantic Art and the Prospect of India. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005. Print.

Sutton, Thomas. The Daniells; Artists and Travellers. London: Bodley Head, 1954. Print.