Creation Date

c. 18th century

Width

33 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

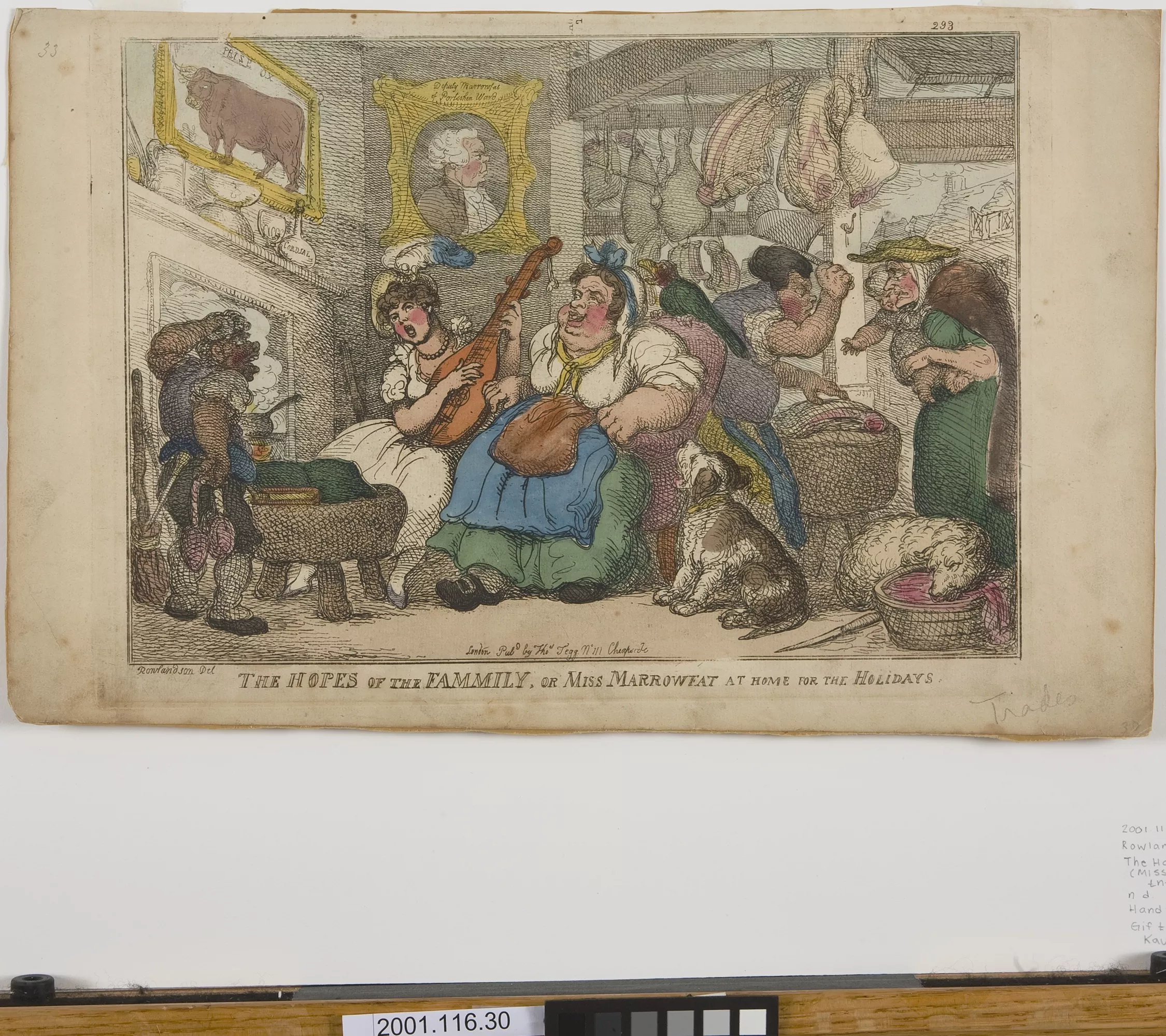

In this busy scene, the young Miss Marrowfat entertains the family (and whoever else may happen to enter the butcher shop, apparently) with the musical "skills" she has acquired at boarding school. The opposition between Miss Marrowfat's fashionable accomplishments and her grubby commercial surroundings (her origins) serve to satirize her pretensions to the former; as a result, the image produces an interesting commentary on class distinctions and social mobility.

The scene of this print is a butcher’s establishment, understood as the shop and residence of the Marrowfat family. In the center of the scene, the butcher’s daughter sits by the fire playing a lute. She wears an elegant white dress with an empire waist, a necklace and earrings, and a hat or turban with a large feather. On the wall above Miss Marrowfat is a portrait in an elaborate gold frame depicting a well-dressed man in profile that is labeled “Deputy Marrowfat of Portsoken Ward.” This may be the father of the family and the same man as the butcher on the right. Another picture of a “Prise Ox” hangs in a gold frame above the mantel, on top of which sits a decanter of “Cordial” and a glass. These fine objects contrast starkly with the beer stein on the mantel and the rest of the surroundings. Mrs. Marrowfat sits in an armchair next to her daughter, dressed in much humbler clothing. Miss Marrowfat's sheet music is propped on top of a low butchers’ block; a short dark figure, presumably the butcher's apprentice who has been interrupted in his work by the noise, stands beside it, scratching his head. A dog and parrot sit next to Mrs. Marrowfat and appear to be howling and squawking in protest. Behind them the butcher cuts up meat for a customer, an old stooped crone with a baby on her hip. In the lower right corner a sheep, its throat cut, bleeds into a tub. Cuts of meat hang from the rafters in the background, and we can see out into the street beyond.

This print satirizes the figure of the accomplished woman and the role of artistic skills in upward mobility. As an "accomplished woman," Miss Marrowfat represents her family's hope of moving upwards in society: by going to a female boarding school and acquiring a fashionable education, she may be able to marry above her station. Performing her accomplishments—dressing well and playing music for others—is the only means at her disposal to attract a well-off husband. Style and art are thus used to refashion Miss Marrowfat as an artistic commodity in the marriage market. The success of this refashioning, however, is questionable, and Miss Marrowfat’s accomplishments are satirized by means of two main contradictions. The first is that her musical skills are questionable. She plays a lute, which was not considered a genteel instrument by the late-eighteenth century and was instead associated with marginalized populations of southern Europe. Her gaping mouth and ruddy complexion suggest that she is laboring unnecessarily, and the strain of her own noise appears to be accompanied by the sounds of the open-mouthed dog and parrot; the whole scene produces the impression of an unfortunate cacophony. The second contradiction consists in the discrepancy between Miss Marrowfat's carefully stylish appearance and her gritty surroundings, the bloody interior of the butcher's shop. The French style of her costume and the Italian associations of the lute contradict the characteristically English occupation of butchering. Miss Marrowfat’s white dress and skin, highlighted by her brightly flushed cheeks, are particularly contrasted with the darkened figure in the foreground. Although there are other signs of middle-class pretension in the room, such as the gilt-framed pictures, Miss Marrowfat seems to have turned herself into a commodity that no one who would normally visit this establishment would want to buy: the haggard female customer on the right is the polar opposite of an attractive potential husband. Finally, because this quasi-domestic space is open to public commerce and the street, Miss Marrowfat is constructed as putting herself too far forward into the public sphere. Her fashionableness and artistic accomplishments register as showiness that is inappropriate for both her class and her gender.

Locations Description

The butcher’s establishment in this print may be set in Portsoken Ward, as “Portsoken Ward” is written on the portrait frame hung on the back wall. This was a district located in the eastern part of London near Aldgate, outside the former London Wall, and would have been considered an unfashionable area in the early-nineteenth-century.

Although the setting for this image is a butcher’s establishment, the print also references female boarding schools: Miss Marrowfat is home for the holidays from one of these schools, which sprang up at the end of eighteenth century. They originally taught practical skills—such as arithmetic, bookkeeping, English, natural history and needlework—for flat fees that ranged from forty to two hundred guineas a year. For ten to fifty guineas more, a student could also be taught French, drawing, dancing, and music, but these extra subjects soon became the core curriculum. However, many criticized these skills as impractical and argued that they prevented women from gaining the education they needed to become good wives and mothers.

Publisher

Thomas Tegg

Collection

Accession Number

2001.116.30

Additional Information

Bibliography

Bermingham, Ann. “The Aesthetics of Ignorance: The Accomplished Woman in the Culture of Connoisseurship.” Oxford Art Journal 16.2 (1993): 3-20. Print.

---. Learning to Draw: Studies in the Cultural History of a Polite and Useful Art. New Haven: Yale UP, 2000. Print. The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

Kowaleski-Wallace, Elizabeth. Consuming Subjects: Women, Shopping, and Business in the Eighteenth Century. New York: Columbia UP, 1997. Print.

Miller, P.J. “Women’s Education, 'Self-Improvement' and Social Mobility—a Late Eighteenth-Century Debate.” British Journal of Educational Studies 20 (1972): 302-15. Print.

Pointon, Marcia. Strategies for Showing: Women, Possession, and Representation in English Visual Culture, 1665-1800. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1997. Print.

Pullan, Ann. Fashioning a Public for Art: Ideology, Gender and the Fine Arts in the Englsih Periodical c. 1800-1825. Diss. U of Cambridge, 1994. Print.

Rauser, Amelia. “The Butcher-Kissing Duchess of Devonshire: Between Caricature and Allegory in 1784.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 36.1 (2002): 23-46. Print.

Theobald, Marjorie R. “The Accomplished Woman and the Property of Intellect: A New Look at Women’s Education in Britain and Australia, 1800-1850.” History of Education 17 (1988): 20-31. Print.