Creation Date

1819-1820

Height

23.5 cm

Width

19 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

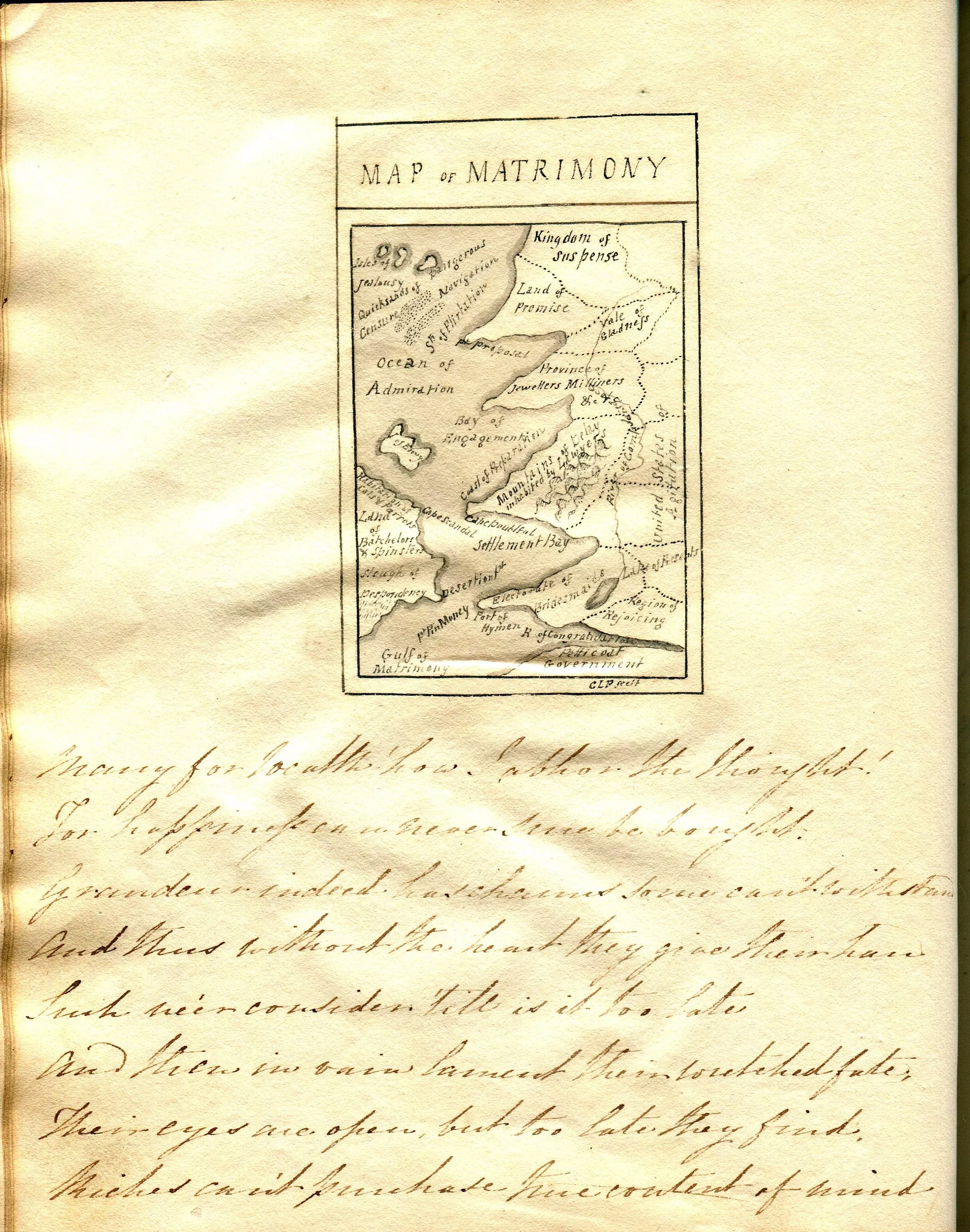

Across the upper half of this album page a map has been created in black ink and brown wash. Identified at the top of the page as a “Map of Matrimony,” it charts the imaginary terrain that must be traversed by the traveler who wishes to enter the married state. That journey would, in the allegorical language deployed here, take a traveler from the “Land of Batchelors and Spinsters,” across the “Gulf of Matrimony,” to the “Land of Promise” and the “Vale of Gladness.” The map also identifies the obstacles that might impede aspirants to marriage. These include, just beyond the “Coast of Preparation,” the “Mountains of Delay inhabited by Lawyers” (here the map-maker gives a nod to the conflicts over marriage settlements that nineteenth-century lawyers might well exacerbate as a way to increase their fees). They also include, in the map’s top left-hand corner, the area that is identified with the warning “Dangerous Navigation”: the journey toward conjugality might come to a premature end should the voyage take the traveler among the “Quicksands of Censure” (malicious gossip) or the “Isles of Jealousy.” At the bottom of the map is a domain named “Petticoat Government”: the term applied, comically and misogynistically, to families where wives wielded more power than husbands. The inclusion of this domain suggests that unhappiness is just as much the custom of the country in the land to the east of the “Gulf of Matrimony” as it is in “Land of Batchelors and Spinsters” to the west, even though the latter encompasses (in this map-maker’s nod to the allegorical landscape of sin depicted in John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress) a “Slough of Despondency.” A frame has been drawn in ink around the map, with the artist’s signature placed inside it: “C.L.P. fecit [made it].”

In including lands inhabited by Jewellers and Milliners (who dwell in the Province at the map’s center) as well as by Lawyers, this “Map of Matrimony” acknowledges candidly the commercial transactions that marriage involves. That account of marriage is offset, however, by the more idealist view adopted by the verses, written out in a messy hand, which occupy the lower half of this same album page. They read:

Marry for Wealth! How I abhor the thought!

For happiness can never sure [?] be bought

Grandeur indeed has charms some can’t withstand

And thus without the heart they give their hand

Such ne’er consider till is it [sic] too late

And then in vain lament their wretched fate

Their eyes are open but too late they find

Riches can’t purchase true content of mind.

The verses, which are unsigned, continue onto the facing page of the album:

Thus from indifference they proceed to hate

Then how unhappy is the marriage State!

Whene’er I wed true love shall guide my way

And when I love I’m sure I can obey

Then inclinations will with duty join

And every wish of his will then be mine

By the time this album was assembled in 1819 (the date stamped on its cover) and 1820 (the date that accompanies some of the content inscribed on its pages), allegorical maps had been part of Anglo-American and European print culture for more than a century and a half. This cartographic tradition began in 1654 when a map entitled the Carte [Map] de Tendre (generally attributed to the engraver François Chauveau) was included in the first volume of Madeleine de Scudery’s novel Clélie. (Notably enough, this founding example of the genre –much imitated and sometimes parodied—omits, in its charting of the land of love, any reference to the married state.) In 1772, the English poet and essayist Anna Letitia Barbauld collaborated with the publisher Joseph Johnson to produce, as a visual accompaniment to a poem that Barbauld had addressed to her husband, an engraved map titled A New Map of the Land of Matrimony, Drawn from the Latest Surveys. It is easy to imagine how these cartographic exercises, both the sort disseminated in print and those that were instead confined to hand-drawn pages in albums, might have been valued as drawing-room entertainments. Think of the flirtatious conversations that they could spark: did Julia Powys and her friends pore over this page and joke about exactly where on this map they would plot their own life journeys?

The uncertain provenance of this album, now owned by the New York Public Library, makes the identity of the Julia Powys whose name is stamped in gilt on the book’s front cover a matter of guesswork. It is possible that the compiler of this album may indeed be identified with the Julia Barrington Powys who lived in Hardwick House in Whitchurch on Thames in Oxfordshire, and who through her marriage became a family connection of Jane Austen’s (her husband’s sister was married to Austen’s cousin, Rev. Edward Cooper). If this identification is correct, this Julia Powys had been married only two years when she and her acquaintance commenced filling up the pages of her book—something they did, sometimes, by collecting humorous material about courtship and marriage and ill-sorted married couples and placing it alongside the volume’s more sentimental content. On one page in this album we find, for instance, a handwritten poem titled “A Lady’s Objections to Matrimony”; turn the leaf over and we find an “Answer to the Lady’s Objections”.) If this identification is correct, it also makes the humor and outright cheekiness of many of the materials that this album assembles rather poignant: this Julia Powys died young, four years into her marriage, at age 25.

Collection

Accession Number

Pforz. BND-MSS