Exhibit

Creation Date

1820

Height

24 cm

Width

15 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

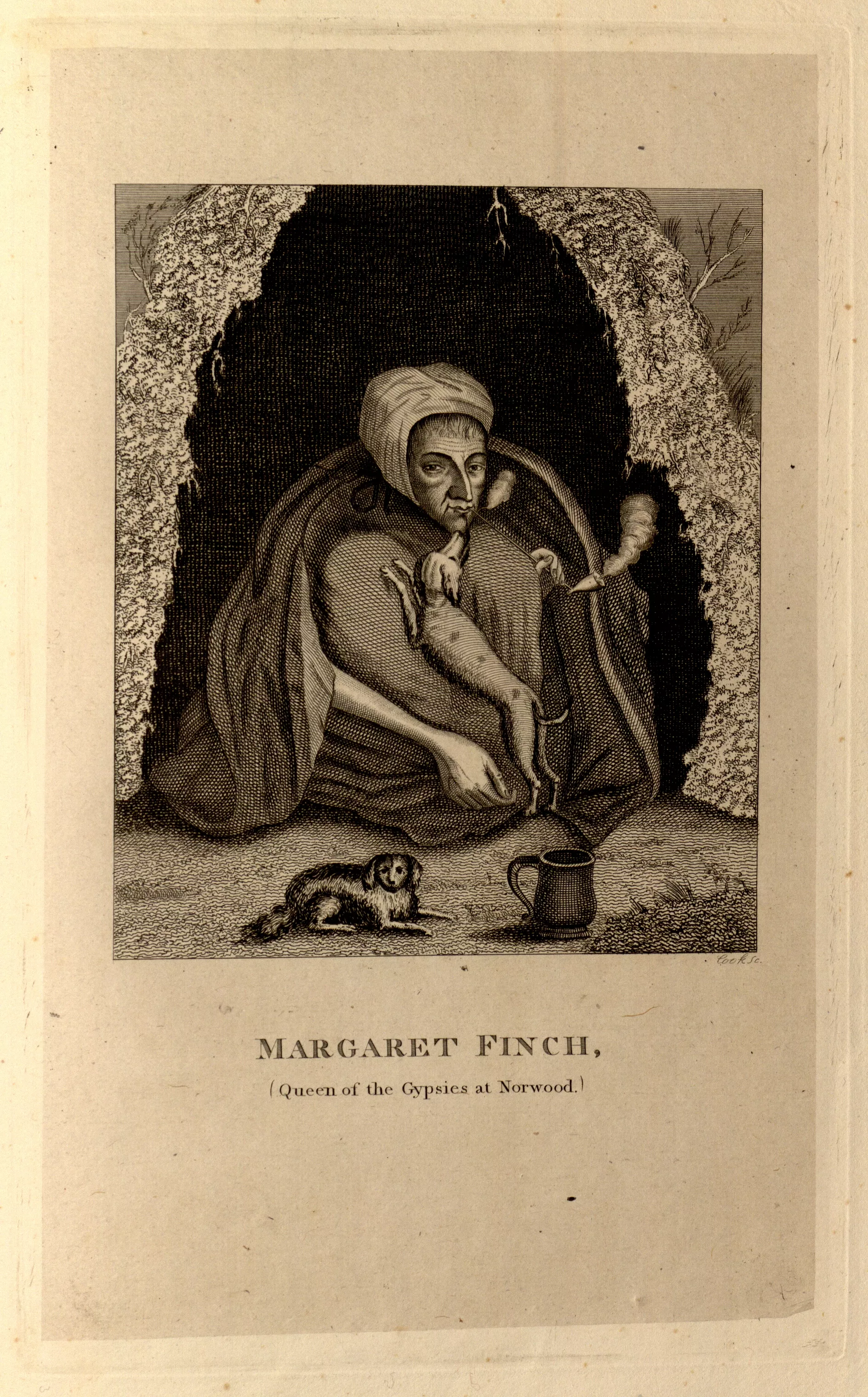

In a small, dark, cave-like dwelling, a woman with a creased brow and elongated nose sits crouched with her knees to her chest. She wears a white bonnet and large cloak, and she smokes a slender clay pipe. A dog, standing on its hind legs, licks her chin, and a second canine companion lies in the foreground beside a scroll-handled mug.

Ethnographic images such as these strove to classify gypsies as an identifiable racial group and to differentiate between particular types of gypsies (such as the rugged, Amazonian gypsy woman and the decrepit and elderly gypsy hag). Such images were included in both encyclopedic volumes of novel persons, which attempted to archive eccentric types, and more focused scholarly treatises on the supposed cultural and biological differences of England’s domestic other.

Margaret Finch’s status as “Queen of the Gypsies” contributes to a common construction of Romanie culture as organized along a separate, but parallel hierarchy that mimics and perverts the authority of the English crown.

Margaret Finch is said to have lived during the reign of George II, the period in which vagrancy laws directed at gypsies began to proliferate. The 1744 Vagrancy Act mandated that gypsies, beggars, strolling actors, peddlers and gamblers refusing to work for usual or common wages could be whipped or imprisoned by local magistrates (Mayall 258). In this way, any person refusing to participate in a wage-based system of labor was deemed criminal. The 1810 Licensing Act required the licensing of vagabonds, gypsies, hawkers and peddlers (Hawkes 13). This system of identification contributed to the surveillance of wandering persons and helped to enforce local ordinances specifying the maximum stay of non-residents in a town or its outskirts. Illustrative of local laws that upheld the 1744 Vagrancy Act, this resolution stated that “all persons pretending to be gipsies, or wandering in the habit or form of Eqyptians, are by law deemed to be rogues and vagabonds, punishable by imprisonment and whipping” (Mayall 258). The 1822 Turnpike Roads Act imposed “a fine of 40s on any Gypsy encamping on the side of a turnpike” (Hawkes 13).

Under George IV, vagrancy measures were aimed more specifically at “anyone pretending to tell fortunes by palmistry” and more generally at anyone “wandering abroad and lodging under any tent or cart, not having any visible means of subsistence, and not having a good account of himself” (Hawkes 14). Throughout this period legal settlement remained a prerequisite for poor relief, meaning that the illegally settled, unsettled or wandering poor were routinely excluded from community or church-based assistance (Lloyd 117). Through the so-called “Speenhamland system,” parishes subsidized wages according to the parishioner’s need, determined by the cost of bread and number of dependents (Lloyd 115). In this way, most discussions of poverty revolved around the adequacy or inadequacy of earnings, and thus excluded those who did not participate in a wage-based economy.

Margaret Finch’s status as “Queen of the Gypsies” contributes to a common construction of Romanie culture as organized along a separate, but parallel hierarchy, which mimics and perverts the authority of the English crown. This parallel aristocracy is thought to be laughably squalid, thus solidifying their status as “domestic others” who shadow but misinterpret the structures of English society (Nord 5). The insistence on this alternative social structure also underscored the belief that gypsies did not qualify for any assistance from the crown, as they existed entirely outside of its purview. Of course, they were not likewise excused from the courts or laws established by the crown.

Aside from the predictable advice regarding work, religious devotion and frugality in The Times article (see "Associated Texts") we find a curious preoccupation with dogs as signifiers of excess. Dogs are presented as luxuries that may be afforded by the rich, but are so impractical for the poor that their retention disqualifies their owners from charitable assistance. A character like Margaret, Queen of the Gypsies, would have been understood as violating almost all of the stipulations set out by The Times, yet, her violation of more abstract obligations, such as civility toward superiors, are comparatively difficult to image. The presence of not just one, but two dogs (neither of which seem engaged in a “useful” activity) solidifies Margaret’s status as undeserving of, and even defiant toward, charitable aid. The scroll-handled mug, which suggests the possibility of Margaret receiving alms, is thus undermined by the presence of her superfluous canines.

In the early years of the nineteenth century, Michael Kramp argues that the “English conception of the gypsy as a threat to heterosexual and labor (re)production” is reconceptualized through the figure of the deformed and repulsive gypsy hag (Kramp 1339). The old fortune-teller, the “antithesis of sexual allure,” neither endangers heteronormativity nor poses the threat of miscegenation. Whereas late-eighteenth-century depictions of gypsy femininity emphasized their aggressive sexuality, Margaret Finch, in her decrepit and static state, becomes an attraction rather than an attractor.

Collection

Accession Number

Thordarson T 510 v. III

Additional Information

Bibliography

Caulfield, James. Portraits, Memories and Characters of Remarkable Persons. London: H.R. Young and T.H. Whitely, 1820. Print.

Gregory, James. “Eccentric Biography and the Victorians.” Biography (2007): 342-376. Print.

Hawkes, Derek and Barbara Perez. The Gypsy and the State: The Ethnic Cleansing of British Society. Oxford: Alden P, 1995. Print.

Kramp, Michael. “The Romantic Reconceptualization of the Gypsy: From Menace to Malleability.” Literature Compass (2006): 1334-50. Print.

Lloyd, Sarah. “Poverty.” An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age: British Culture 1776-1832. Ed. Iain McCalman, et al. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. 114-125. Print.

Mayall, David. Gypsy Identities 1500-2000: From Egipcyans and Moon-men to the Ethnic Romany. New York: Routledge, 2004. Print.

Nord, Deborah Epstein. Gypsies & the British Imagination, 1807-1930. New York: Columbia UP, 2006. Print.

Olsen, Kirstin. Daily Life in 18th-century England. Westport: Greenwood P, 1999. Print.