Creation Date

1830

Height

8 cm

Width

11 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

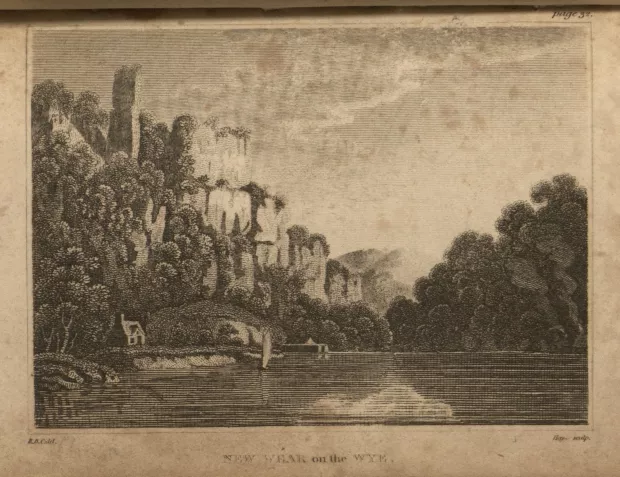

Cliffs, presumably near New Weir (spelled “New Wear” in the title), stretch upward, taking up most of the left half of the print. In the foreground, at the foot of the cliffs, is a small house. A sailboat floats on the river. To the right of the boat and further downstream, the wharf of the ironworks extends into the water. The river cuts around a patch of trees that provides the background for the wharf, and apparently doubles back on itself after passing more trees. A forest, with two plumes of smoke, takes up the right margin of the print, two plumes of smoke rising from the tops of the trees. At the horizon, two or three hills, possibly wooded, meet the sky. Some clouds hang from the topmost border of the print. New Wear on the Wye was first published July 20, 1811, bound in book form as an accompaniment to the first edition of Robert Bloomfield’s The Banks of Wye: a Poem in Four Books.

New Wear on the Wye features the ironworks at New Weir ("New Wear"). It was completed circa 1813, fifteen years after the 1798 publication of William Wordsworth's "Lines Composed a few miles above Tintern Abbey, on revisiting the banks of the Wye Valley during a tour, July 13, 1798" and the subsequent "new phase in man's relationship to the natural world" (Andrews 90). Given its relatively late creation date, it is not surprising that the piece, rather than focusing on the picturesque, instead investigates the effects of the natural scene on the human viewer.

The primary significance of the piece as it relates to Romantic culture as a whole is in its depiction of the picturesque. The picturesque, which captivated and engaged Romantic viewers, was composed primarily of contrast—contrast in textures, colors, sizes, and shapes. During the late 1700s and the first half of the 1800s, the Wye River Valley, especially the stretch of river from the town Ross-on-Wye to the city of Chepstow, was a favorite spot for British tourists to observe the picturesque. Recreations such as these only furthered public desire to witness the “succession of nameless beauties” described and portrayed in works like Robert Bloomfield’s The Banks of Wye (1811) and William Gilpin’s Observations on the River Wye (1782). The focus on the personal significance of the natural scene indicates what Malcom Andrews calls the “new phase in man’s relationship with the natural world” (86) that began in the years following the publication of Wordsworth’s “Lines composed a few miles above Tintern Abbey on revisiting the banks of the Wye Valley on a tour, July 13, 1798.”

Thematically, the work is similar to most representations of the picturesque landscape. The placement of man-made objects (the cottage, the boat, the dock) in direct juxtaposition with the massive cliffs provides the contrast central to a properly picturesque scene. The plumes of smoke, whose source is unclear, filter through the canopy of the forest, manifesting yet another level of contrast in the interaction of the human and natural worlds. Moreover, the entire scene coheres in a diverse variety of contrasting textures: the smooth sail and the rough cliffs, the bunched leaves, the calm river and the silky smoke. In keeping with the later Romantic emphasis on the interior state of the viewer, the work also suggests a more personal theme: the solitary house amidst the massive cliffs and hills imbues the work with a sense of solitude, drawing the viewer into empathy with the unseen, human inhabitants of the picturesque scene. This empathy in turn works to invoke the sublime, as the magnificent size of the cliffs dwarfs the cottage whose imagined community we, as fellow viewers, have seemed to join.

The popularity of the Wye Tour, a picturesque tour through the England-Wales border down the River Wye, increased exponentially during the 1780s and the decades that followed (though the Wye river was a popular site for at least twenty-five years before Gilpin’s tour); this was due in large part to the tour guide-book Observations on the River Wye, written by the Reverend William Gilpin and published in 1782. The tour focused on the natural beauty of the Wye Valley, especially the part of the Valley that fit Gilpin’s idea of the “correctly picturesque”—usually characterized by a natural object (e.g., a tree, a stone, cliffs; anything not human-made) which stood out in stark contrast to its surroundings and was often in close proximity to people or human-made objects (factories, bridges, and the like). The tour lasted two to three days by boat (the most common form of travel for tourists) or carriage (used only by the very wealthy), and significantly longer by foot; William Wordsworth and his sister, Dorothy, took a walking tour of the Wye Valley in 1798 (see William Wordsworth’s memorial poem “Lines composed a few miles above Tintern Abbey on Revisiting the banks of the Wye Valley during a tour, July 13, 1798”). The most common form of travel was by pleasure boat, which featured a canopy to shield tourists from the wind, sun, and rain; a handful of tables for writing or drawing; and several oarsmen who acted as de facto tour guides and cost three to four guineas for two days' employment (Moir 125). The tour extended, as Gilpin noted, “To [Chepstow] from Ross, which is a course of near 40 miles” and featured “a succession of the most picturesque scenes” (Gilpin 7). Highlights included Ross-on-Wye, Goodrich Castle, Symond’s Yat, Monmouth, Tintern Abbey, Piercefield, Chepstow Castle, and, finally, the junction of the Rivers Wye and Severn at Chepstow.

Picturesque tourism as an industry was largely popularized by the publication of Gilpin’s Observations on the River Wye in 1782. Tourists of the "picturesque" traveled to Scotland, North and South Wales, the Wye Valley, and the Lake District (in northwest England) in search of scenery manifesting this ideal. Oftentimes, tourists brought watercolors to quickly paint or sketch the scenes that most captivated them, in the fashion of Gilpin. These tourists, and their dogged pursuit of the picturesque, would later be lampooned by caricaturists in the early years of the 1800s, but picturesque tourism maintained significant popularity until the mid-nineteenth century.

Associated Works

Locations Description

The Wye River

The Wye River rises on Plynlimon Mountain in Wales and flows southeast for 130 miles. The last forty miles of the river, beginning at Ross-on-Wye, made up the Wye Tour during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Gilpin described its beauty as related primarily to its “mazy course” and “lofty banks” (Gilpin 7). The river winds along the English-Welsh border until it empties into the River Severn at Chepstow, and features the ruins of several castles, abbeys, and the like along its banks.

New Weir

Generally accepted as the “second grand scene of the tour,” the ironworks at New Weir (identified as “New Wear” by Hayes) exemplify the picturesque qualities created by the interaction of the industrial and natural worlds (M. Andrews, In Search of the Picturesque 93). Andrews effusively writes that “the natural scene itself is awesome, and therefore positively enhanced by the presence of industry” (Andrews 93); this sentiment is echoed by Thomas Whateley, another traveler on the Wye, who at New Weir observed with awe “a path, worn into steps narrow and steep, winding among the precipices,” and noted how “the sullen sound from the strokes of the great hammers in the forge . . . deadens the roar of the waterfall” (qtd. in Andrews 93). Gilpin confirms that “the contrast of all this business, the engines used in lading, and unlading, together with the solemnity of the scene, produce all together a picturesque assemblage” (Gilpin 22).

Copyright

Copyright 2009, Department of Special Collections, Memorial Library, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI

Collection

Accession Number

PR4149 B6 B3 1813

Additional Information

Bibliography

Andrews, Malcom. In Search of the Picturesque. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1989. Print.

Bloomfield, Robert. The Banks of Wye: a Poem. In Four Books. London, 1811. Print.

Gilpin, William. Observations on the River Wye. 1782. Oxford: Woodstock Books, 1991. Print. Revolution and Romanticism, 1789-1834.

Kaloustian, David. “Bloomfield, Robert (1766–1823).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Ed. Lawrence Goldman. Oxford: OUP, 2004. 21 Aug. 2013.

Moir, Esther. The Discovery of Britain; The English Tourists. London: Routledge & K. Paul, 1964. Print.