Exhibit

Creation Date

1830s

Height

17 cm

Width

10 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

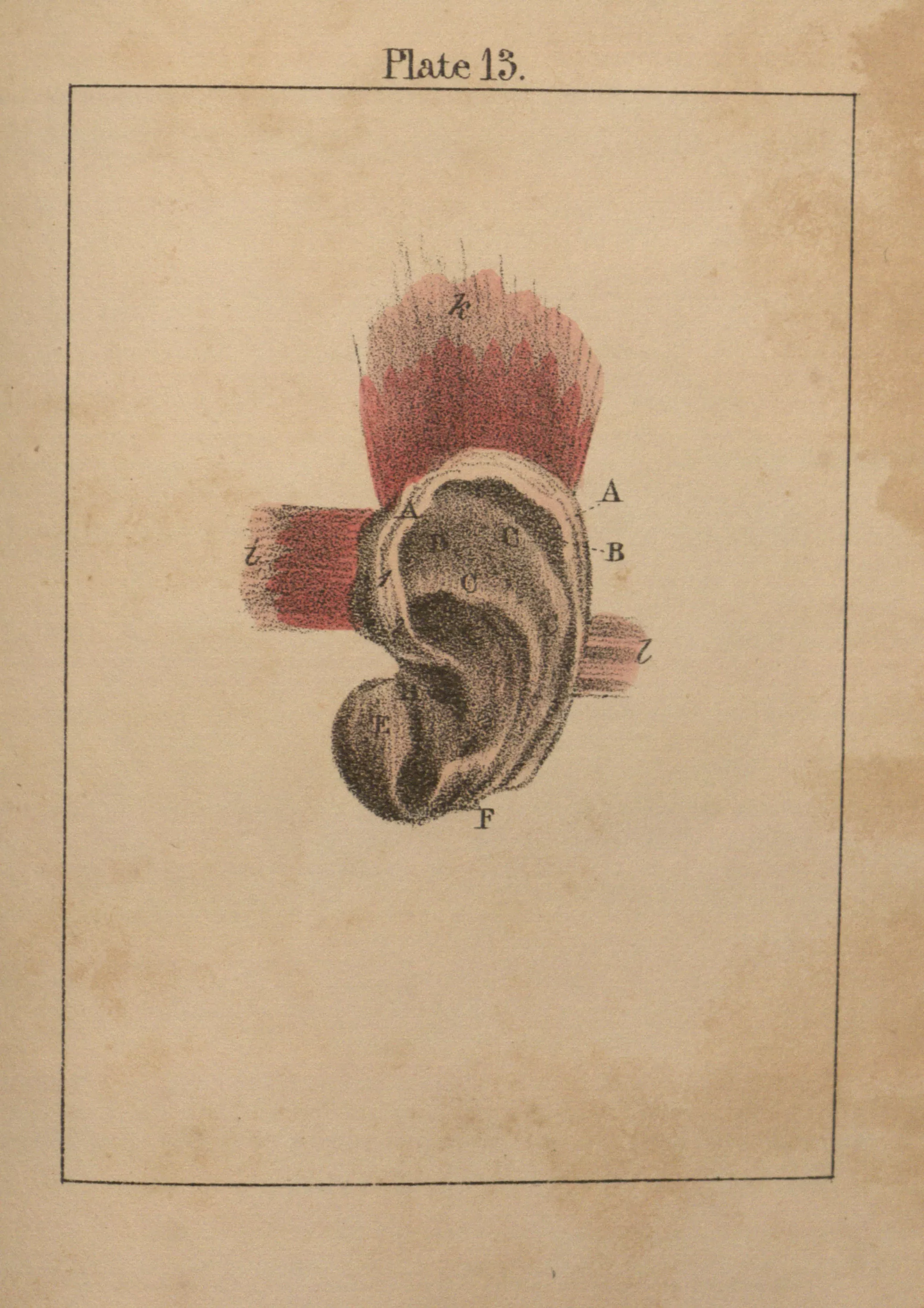

The series of plates given in this gallery depicts the ear and how it works. This image, Plate 13 of Bell's illustrations, depicts the ear without the skin. The numbers and their labels are given below:

A: the helix

B: the unnamed cavity

C: the antihelix

D: its cavity, called the scapha

E: the tragus

F: the antitragus

G: the concha, or great cavity

Bell further describes the image in the accompanying text:

At the part H is the tube called the external auditory passage, which is cartilaginous at its outer portion, but its inner end is formed by a channel to the temporal bone. From the skin lining this passage, many small hairs stand across: and underneath it, is a set of small glands, which secrete the wax of the ear, and send it through their little ducts into the passage. This wax, which is viscous and bitter, guards the internal parts from insects.

Another helpful text, from Chambers's Edinburgh Journal, is given below, demonstrating what was known about the ear at the time:

The external ear is the natural ear trumpet. It is spread out for the collection of sound, and is formed of a substance named cartilage, which holds an intermediate existence between bone and flesh. In this we observe a purpose: from bone, vibrations of sound would be reverberated, and by flesh they would be absorbed, while such a substance as cartilage is calculated to avoid either reverberation or absorption. It is covered with a very thin skin, and has several channels or depressions, which all lead into one cavity, in which the passage to the drum commences. These channels need not be particularly described, their general purpose of collecting sound being all that is worthy of note. ("The Ear" 410)

In 1828, Bell accepted the Professorship of Physiology and Surgery at the newly opened University of London (Gordon-Taylor). Even after the college incorporated the Middlesex Hospital School and Bell was able to practice surgery there in 1835, his alma mater, Edinburgh, wooed him back to be Chair of Surgery. The estimated publication date of this text makes it likely that the text was written during his time at one of these two schools, which may indicate that the text was either a reference book for beginning medical students in anatomy or an informal way of introducing anatomy to the public. Bell was interested in producing texts that were useful to both scientists and artists. One of his better known texts, Anatomy of Expression, was “justly a favorite of students of anatomy and students of drawing”: in this text, Bell analyzed drawings by Hogarth and others through “the aid of anatomical science, and [demonstrated] how precisely true to nature are the highest delineations of genius” (F. A. 92). It is likely that his own experience and facility with drawing influenced this desire to combine science with art. As an additional influence, however, there was at the time an ongoing discussion concerned with the possible ways in which anatomy influenced human expressions. This conversation, connected to the Romantic fascination with physiognomy, contributed to painters’ and artists’ ability to convey emotion through anatomical verisimillitude and a burgeoning understanding of the function of the muscles and nerves in the face itself (Delaporte).

Bell’s understanding of the ear and the specificity and function of the bundling of different types of nerves (such as auditory nerves) significantly increased scientists’ ability to study acoustics and sound theory in the early nineteenth century. As he noted to his brother, “I consider the organs of the outward senses as forming a distinct class of nerves from the other. I trace them to corresponding parts of the brain totally distinct from the origins of the other” (F. A. 95).

By providing a more explicit account of how nerves connected to the senses—such as the aural—worked, he reduced some of the mystery surrounding the hearing process. Bell’s illustrations dovetail with his text in a way that aligns the visual and the aural: what he describes, we see, even though he is attempting to explain the ineffable process of making sense of sound. Though Romantic culture seemed to give primacy to the sense of sight, this did not necessarily result in the primacy of what was visible; the fascination with the visible carried with it a silent twin, the lure of the invisible. Acts such as looking at ruins or allegorical portraits required moments of memory and reflection—a tracing of what was visible in an invisible realm. Sophie Thomas notes:

. . . an important part of this history . . . is related to how visual and literary culture in the period engages with what is inherently imaginative, and with what borders on the invisible. And more pointedly, with how the epistemology of the invisible functions as a secret counterpart to the visible, structuring it, conditioning it, even doubling it. (7)

Part of the allure of Romantic spectacles such as the phantasmagoria was created by the trappings of illusion and the accompanying uncertainty about what was seen and how it was being seen. Bell participates in this work—which both elevates and unsettles the trustworthiness of the eye—by seeking to lay bare the underlying mechanisms that make hearing possible: to bring the invisible interior to light, and to make it visible, even though sound itself was ephemeral and fleeting. Work like Bell’s strengthened parallels that were frequently drawn between the functions of eye and ear, such as the comparison between spectacles and ear trumpets. In addition, since scientists and philosophers in the Romantic period were just as invested in the way the observer experienced phenomena as they were in the causes and effects of the phenomena themselves, Bell’s text provides an accurate and concise sketch of how the aural senses of the observing body were perceived.

Bell’s "Initial Introduction" is given below:

As rays of light dart forth in all directions from a luminous body, so rays of sound, as they may be termed, issue in every direction from a sonorous body… Sounds obey the laws of reflexion, and although no part of the ear is adapted absolutely to bring them into focus, still its external cartilages are understood by their form and slight motion, to have the power of collection the vibrations and reflecting them onwards to the tympanum. Neither the outward ear, nor the tympanous membrane are essential to sound. Air is essential to sound, though not to light: sound is in fact the vibration of the air communicated to the brain.

This introduction sets up the confluence between the ways of understanding sight and sound that were common at the time Bell was writing; like objects observed by the eye, which were not accurately represented through photography until later in the nineteenth century, sound was similarly impossible to accurately preserve. As Jonathan Sterne notes in The Audible Past, “before the invention of sound-reproduction technologies, we are told, sound withered away. It existed only as it went out of existence” (Sterne 1). Sound had to be described in visual terms because there was no capacity to replay or recreate sounds; what was spoken, sung, or played was truly lost forever, which only began to change with the introduction of new devices like the telephone and the phonograph. This gallery looks at sound during a time when it was not as commodified or industrialized as it was later in the nineteenth century. However, the way that Romantic individuals had to visualize sound shaped the way that recording technology developed, as the Romantic imagination envisioned the possibility of sound made concrete and accessible for repeated listening. These kinds of mindsets paved the way for machines like the ear phonautograph, an early ancestor of the telephone and the phonograph, which was “an excised human ear attached by thumbscrews to a wooden chassis . . . [that] produced tracings of sound on a sheet of smoked glass when sound entered the mouthpiece” (Sterne 31). The way that the ear itself was understood, as well as the visual register in which sound had first been “recorded,” made the ear phonautograph an understandable, if grisly, foray into sound reproduction.

Locations Description

University of London. Middlesex Hospital School. Edinburgh.

Collection

Accession Number

RE26 O6 B45 074

Additional Information

Bibliography

Bell, Charles. The Organs of the Senses Familiarly Described. London: Harvey and Co., 1803. Print.

DeLaporte, Francis. Anatomy of the Passions. Stanford UP, 2008. Print.

F. A., "Sir Charles Bell." Fraser's Magazine Jan. 1875: 88-100. Print.

Gordon-Taylor, Gordon. Sir Charles Bell: His Life and Times. Edinburgh: E. & S. Livingstone Ltd., 1958. Print.

Sterne, Jonathan. The Audible Past. Durham: Duke UP. 2003. Print.

"The Ear." Chambers's Edinburgh Journal Jan. 1837: 410-411. Print.

Thomas, Sophie. Romanticism and Visuality. New York: Routledge, 2008. Print.