Exhibit

Creation Date

1800

Height

15 cm

Width

10 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

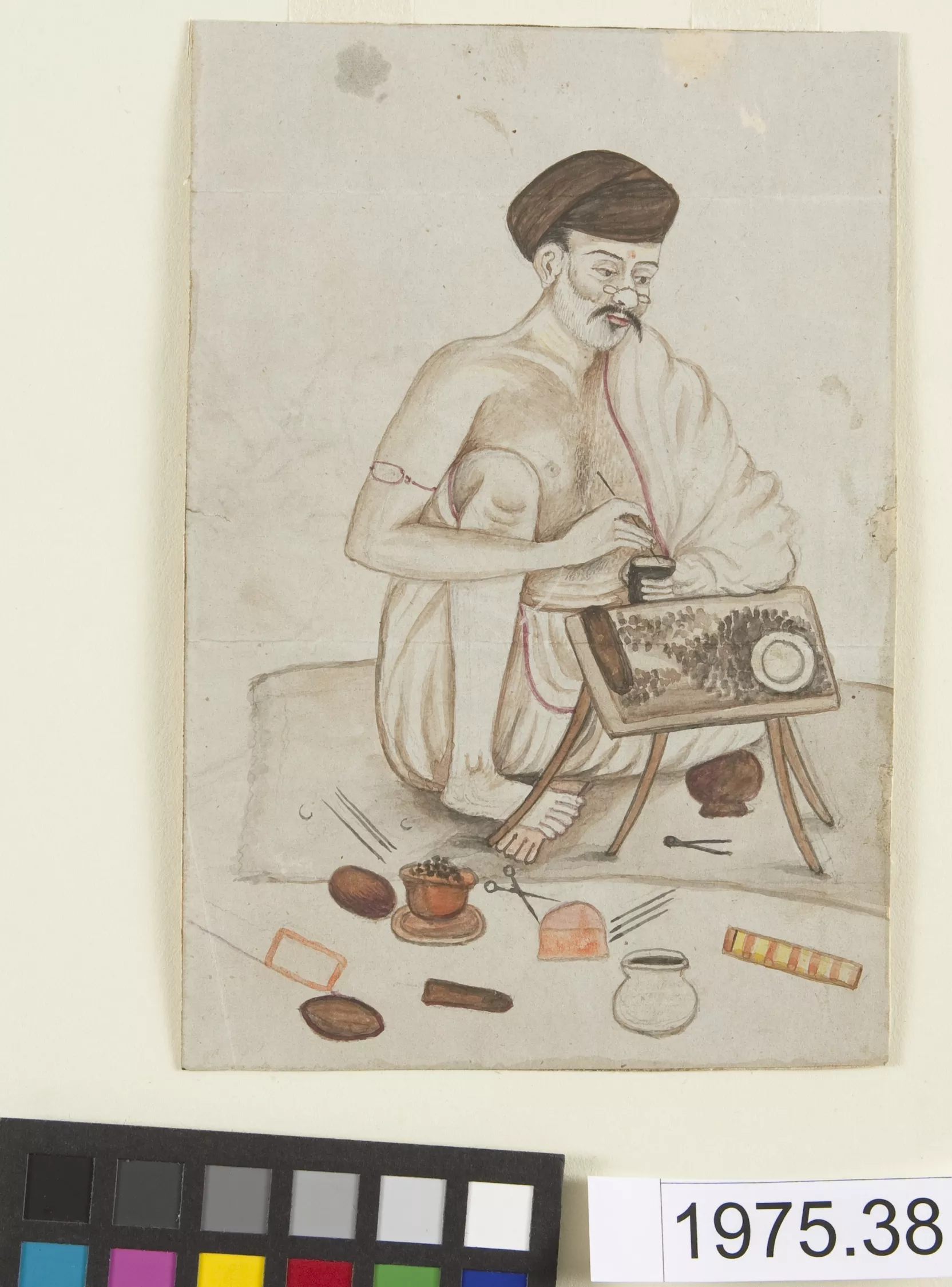

The art historian Pramod Chandra describes the subject of this image as follows:

A painter wearing a pince-nez and surrounded by vials of paint, brushes, and other tools is busy at work on a painting which he has placed on a stool. Series of paintings called firkas, illustrating the various professions, trades and crafts were in great demand by British residents. (49)

The painter’s pince-nez, made up of cloth wrapped around the artist’s head, is a type of turban (pugri) worn by many men in India in the mid to late nineteenth century. The painter’s costume is similar to that of the subject in Maker of Bangles: both artisans are adorned with arm bands across their right biceps and wear a short loincloth (langoti). In the mixed Muslim-Hindu society which the British colonized, clothing (especially the type of headdress) delineated religious affiliation, social status, regional locale, and caste (Tarlo 26). Indian artists, acutely aware of these costume differences, incorporated them into their images.

With a shawl (chadar) draped across his left shoulder, the painter-subject of the image reminds the viewer of early (first to second century) portrayals of Buddha in which the latter's left shoulder is covered with a transparent cloth (samghati). In making this historical connection between the painter and the Buddha, the artist evokes the Islamic-Hindu philosophies that associate artistic creation with divine creation. This association is evidenced by the Hindu ritual—still practiced today—in which an artist uses a golden needle or a final brushstroke to symbolically open the eyes of a divine image (Eck 172). Additionally, artists evoke the gods prior to embarking on their artistic journey by holding the brush to their forehead and muttering ‘Hail to the god Ganapati’ (M. Chandra 38)

Given the close attention to clothing in this image, we can conclude then that this painting (probably produced for a European patron) engaged in the visual classification of Indians common to artistic works of the period. However, the subject's likeness in costume to early images of the Buddha suggests that the artist not only drew on Indian religious beliefs, but that he also claimed a higher status for himself by portraying the artist "type" as divine.

During the time this image was created, Britain established a centralized government in India. Because it is unknown who the artist was and where he was located during the execution of the work, it is unclear what types of cultural interactions may have occurred between the artist and his patron. Mildred Archer states that Company paintings were made for and marketed to European patrons that were employed by the East India Company (Archer 1-19). However, sultans and princes under British rule may also have been patrons of Company-style paintings, as many Indian princes and rajahs in the late eighteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries were patrons and collectors of European art (Sutton 15-17). This trans-cultural contact through the exchange of art had an early precedent in the reigns of the Mughal rulers. One of the earliest recorded accounts occurred in 1580, when Akbar (r. 1556-1605) invited Portuguese Jesuits living in Goa to stay at his palace in Delhi. The exchange of engravings, manuscripts, and books led to the production of a panoply of Christian images that adorned Akbar’s court (Bailey 24-5).

The visual classification of "types" of Indian people is a consistent motif in Company style paintings. This gallery includes several examples of such paintings: The Painter at Work, The Indian Fruit Seller, The Bangle Maker, and The Nobleman Listening to Music. A large collection of Company paintings that depict various types of people—from “The potter firing pots on a small kiln,” to “A man block-printing on cloth,” to a “Prostitute reclining on a couch”—are housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum and in the India Office Library in London (Archer 106).

As one such example of the Company style, A Painter at Work reflects the type of visual classification that came to dominate interactions in India during the Romantic and Victorian periods. Developing scientific theories such as social Darwinism, phrenology, physiognomy, and anthropology augmented the need to hierarchically classify human beings. (Ryan 156-71). In addition to the racial typing that occurred throughout the nineteenth century, the classification of types by profession appears to stem from the social segregation prominent in the caste system. Rather than determining or identifying social status by means of specific bodily features, the caste system distinguishes status according to the professional class one inherits at birth: Brahmins are priests or teachers, Kshatriyas are rulers, Vaishyas are farmers, and Shudras are artisans (Mitter 41). These distinctions were made visible in the types of clothing, especially the types of headdress, which Indians wore.

The caste system, Bayly articulates, was a fluid system that enabled migration into different social spheres through land ownership, marriage, and political conquest. With colonization, however, the caste system was made static through the implementation of “Hindoo Law” and the subsequent categorizing of people in courts and ethnographic surveys. Fixing the caste system served as a way for the British colonizers to regulate and govern a foreign land (Bayly 138).

After the Indian rebellion in 1857 and the introduction of photography into India, an anthropological photographic work, The People of India, was undertaken by the India Office. This album, edited by John William Kaye and J. Forbes Watson, contains 468 photographs of Indian types. These groups of people were categorized by tribe, facial and body features, costume, and, most importantly, what kind of threat they posed to the government as deduced from their role in the Mutiny of 1857 (Ryan 155).

We see then that, after 1857, the Company shifted its focus from classifying Indian bodies in order to regulate trade and commerce to racially typing groups as a way to minimize threats to imperial rule. Company style paintings that depicted artisans did not simply record facial types as did later colonial photographic projects; instead, these initial depictions based their typing on the categories of the caste system.

Locations Description

The East India Company was formed to trade with East and Southeast Asia and India and was instituted by royal charter on Dec. 31, 1600. Although it started as a monopolistic trading company, it soon became involved in politics and acted as an instrument of British imperialism in India from the early eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth century. The company was founded with the hope of dominating the East Indian spice trade. This trade had been a monopoly of Spain and Portugal until the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 gave England the opportunity to appropriate the lucrative market.

Accession Number

1975.38

Additional Information

Bibliography

Archer, Mildred. Company Paintings: Indian Paintings of the British Period. London: Victoria and Albert Museum in association with Mapin Publishing, 1992. Print.

Bailey, Alexander Gauvin. “The Indian Conquest of Catholic Art.” Art Journal 57.1 (1998): 24-30. Print.

Bayly, C. A. Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1990. Print.

Chandra, Moti. The Technique of Mughal Painting. Lucknow: U. P. Historical Society, 1949. Print.

Chandra, Pramod. Indian Miniature Painting; the Collection of Earnest C. and Jane Werner Watson. Madison: Elvehjem Art Center, University of Wisconsin; distributed by the U of Wisconsin P, 1971. Print.

Eck, L. Diana. “Diana L. Eck from Darshan.” Religion, Art and Visual Culture: A Cross Cultural Reader. Ed. S. Brent Plate. New York: Palgrave, 2002. 172-75. Print.

Mitter, Partha. Indian Art. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2001. Print.

Ryan, James R. Picturing Empire: Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire. London: Reaktion Books, 1997. Print.

Sutton, Thomas. The Daniells; Artists and Travellers. London: Bodley Head, 1954. Print.

Tarlo, Emma. Clothing Matters: Dress and Identity in India. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1996. Print.

Vajrā cā rya, Gautamavajra. Watson Collection of Indian Miniatures at the Elvehjem Museum of Art: A Detailed Study of Selected Works. Madison: Elvehjem Museum of Art, 2002. Print.