Exhibit

Creation Date

1835

Medium

Genre

Description

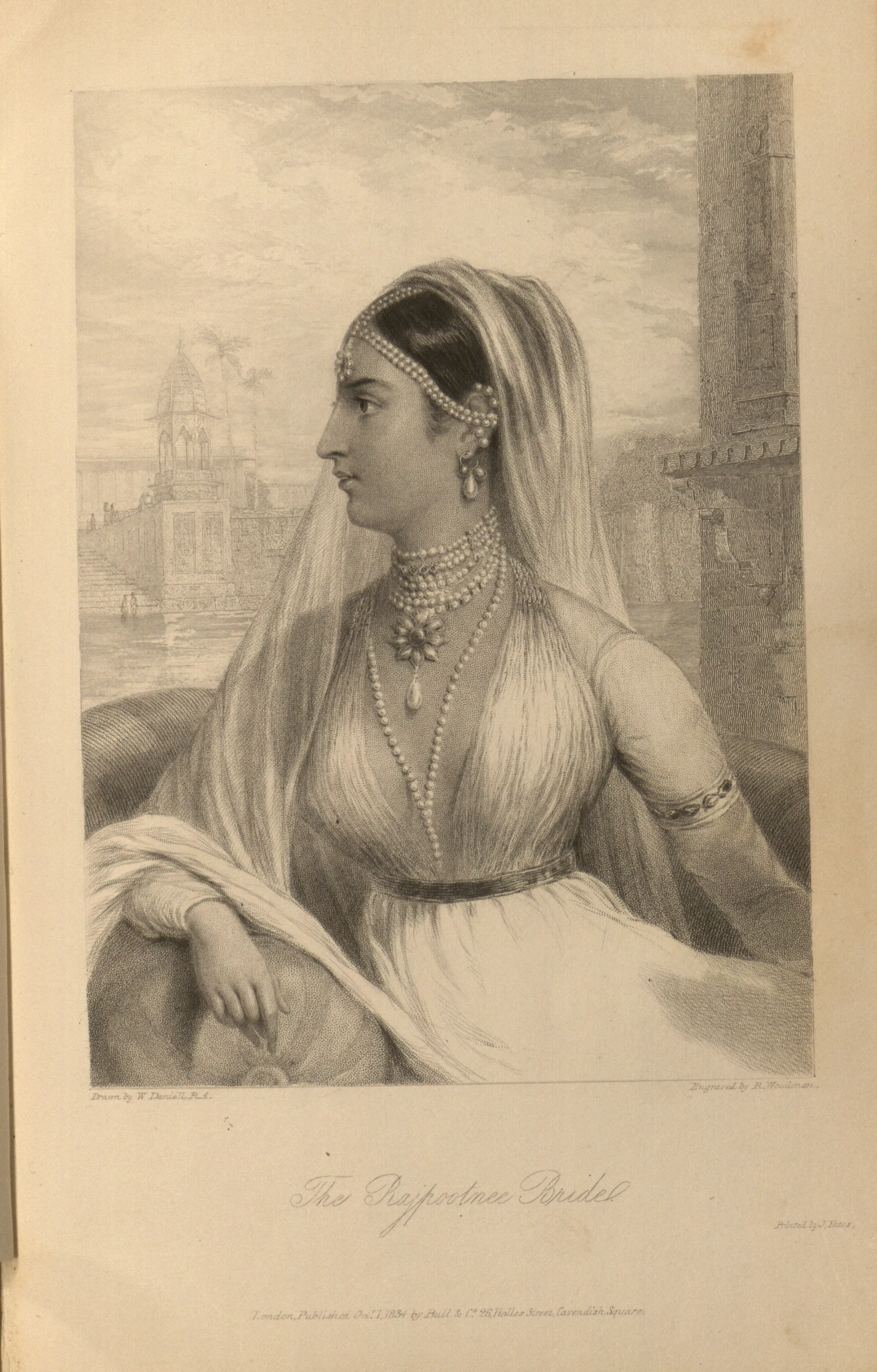

Similar to the central figure of A Hindoo Female, the subject of The Rajpootnee Bride is initially striking on account her size; the female body fills the space of the image. The image is not a portrait of a specific person, but instead gives a generic portrayal of a Rajput bride. However, because the image illustrates a story that describes the bold character and tragic fate of one such bride, this Rajput princess is depicted in such a way as to display her sexual aggressiveness. She looks away so that the viewer can voyeuristically admire her sensuality: her breasts are highlighted by the deep neck of her dress, and a string of pearls draws the eye down to her chest.

The Oriental Annual, or Scenes in India constituted a combination of fictional and instructional manuals that were widely distributed and read; many book reviews regarding The Oriental Annual are found in periodicals of the time.

This image is found in Chapter XII of the Oriental Annual, which is titled, "The Rajpootni Bride." In this chapter, the author describes a feud between the Hara and Rahtore tribes. The Hara’s daughter was

. . . celebrated for her beauty as for her energy of character and masculine understanding. Though subjected to the rigid discipline and jealous seclusion general among the daughters of Rajpootni princes, she had nevertheless partially emancipated herself from a control so repugnant to their impatient yet resolute temperament, and had not only become a partner in the counsels of her parent, but was consulted by him upon every pressing emergency.

She had many suitors and was highly sought after. One day while hunting with her father she came across a lion that tried to attack her:

Instead of exhibiting any of the ordinary fears of her sex, she hastily shook her raven locks from her temples, and her head undauntedly raised, her lips compressed, and her eye flashing with a wild emery, she resolutely attacked the tiger with a dagger which she carried in her girdle, plunging it up to the very hilt in the animal’s body.

The tiger, still alive, turned on the princess. Her father was too far off to help, but a hunter emerged from nowhere and chopped the head off the tiger.

Sometime after this event, the princess eventually falls in love with the son of the chief of the feuding tribe. He asks for her hand in marriage, but her father refuses. Her father is sure that her love for her family is stronger than that for a boy, and he recites a poem recounting her beauty, written above. The princess marries her lover despite the prohibition of her father, and, in the end, the couple commits suicide.

At the age of fourteen, William Daniell accompanied his uncle Thomas Daniell, a landscape painter trained at the Royal Academy, on a journey to India from 1786 to 1794. The first two years were spent in Calcutta preparing Views of Calcutta. After the first two years they traveled to the Punjab Hills and then back to Calcutta in 1971. They began a second tour in 1792, working their way through Mysore and Madras. After staying in Madras from 1793 to 1794 they finally returned to England. Drawings made during these trips were engraved in books and prints (some of which were exhibited at the Royal Academy).

The Daniells arrived in India during a period of political transition, just after the departure of Warren Hastings and prior to the instatement of Charles Cornwallis (1738-1805), the new Governor-General of India. Cornwallis was the first Governor-General appointed under the new India Act of 1784 (passed during William Pitt's term as British prime minister). The act was passed in part as a means of reigning in the Hastings style of government, which was seen as “too indigenous, free-wheeling and popular, too benevolent and multi-national and not British enough” (De Almeida 168). Hastings became known for incorporating native Indians as administrators, financers, and civil servants. The India Act proceeded to centralize Company administration: a six-member Board of Control was created which controlled the Company’s possessions abroad, and the Governor-Generalship was made a Crown appointment with full control over other governors and presidencies in India. Additionally, the act created a centralized British military in India.

Charles Cornwallis (1738-1805) gained experience in the military while serving in America, and was employed to carry out England’s imperialist vision in India. His strategic military victories on land (for example, in Mysore with Tipu Sultan) not only extended England's rule, but also provided sepoys that could be recruited and kept on reserve for the Napoleonic Wars. Additionally, Cornwallis’ belief that “every native of Hindoostan is corrupt” gave way to a purging of Indian natives from administrative positions and forbid mixing or socializing between races. A purification and segregation process, in which hybridity was especially scorned, took place under Cornwallis’s rule (De Almeida 168). Dalrymple claims that “these new racial attitudes affected all aspects of relations between the British and Indians” (Dalrymple 41). Prior to Cornwallis’s strict racial segregation, many British officials were integrated into Indian society by learning the language, adopting Indian dress and mannerisms, and marrying Indian women (bibis). The decline of this integration became apparent with the declining rates of bibis on wills; by the mid-nineteenth century no records of bibis on wills exist (Dalrymple 1). Even though these changes brought about tension between the British and Indians, many British officials continued to be patrons of Indian art (Archer 1-15).

Like The Hindoo Female, The Rajpootnee Bride provides a sexually available and sensual image of the exotic Other. Even though William Daniell does not mention his familiarity with this erotic Indian female, his sketches in 1792 of the voluptuous, bare breasted women on the façade of the temple Karli attest to his encounter with erotic Indian sculptures (Archer 144). The voluptuous, erotic women depicted on Indian temples most likely inspired the seductive qualities of the women in the Daniells' engravings.

Locations Description

The East India Company was formed to trade with East and Southeast Asia and India and was instituted by royal charter on Dec. 31, 1600. Although it started as a monopolistic trading company, it soon became involved in politics and acted as an instrument of British imperialism in India from the early eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth century. The company was founded with the hope of dominating the East Indian spice trade. This trade had been a monopoly of Spain and Portugal until the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 gave England the opportunity to appropriate the lucrative market.

Collection

Accession Number

AY 13 O7 1835

Additional Information

Bibliography

Archer, Mildred. Early Views of India: The Picturesque Journeys of Thomas and William Daniell, 1786-1794: The Complete Aquatints. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1980. Print.

Broughton, Thomas Duer. The First Published Anthology of Hindi Poets: Thomas Duer Broughton's Selections From the Popular Poetry of the Hindoos, 1814. Ed. Imre Bangha. Delhi: Rainbow Ltd., 2000. Print.

Daniell, William and Hobart Caunter. The Oriental Annual, or Scenes in India. Vol. 2. London, 1835. Print. 7 vols. 1834-40.

De Almeida, Hermione and George H. Gilpin. Indian Renaissance: British Romantic Art and the Prospect of India. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005. Print.

Sutton, Thomas. The Daniells; Artists and Travellers. London: Bodley Head, 1954. Print.