Creation Date

1838

Height

18 cm

Width

27 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

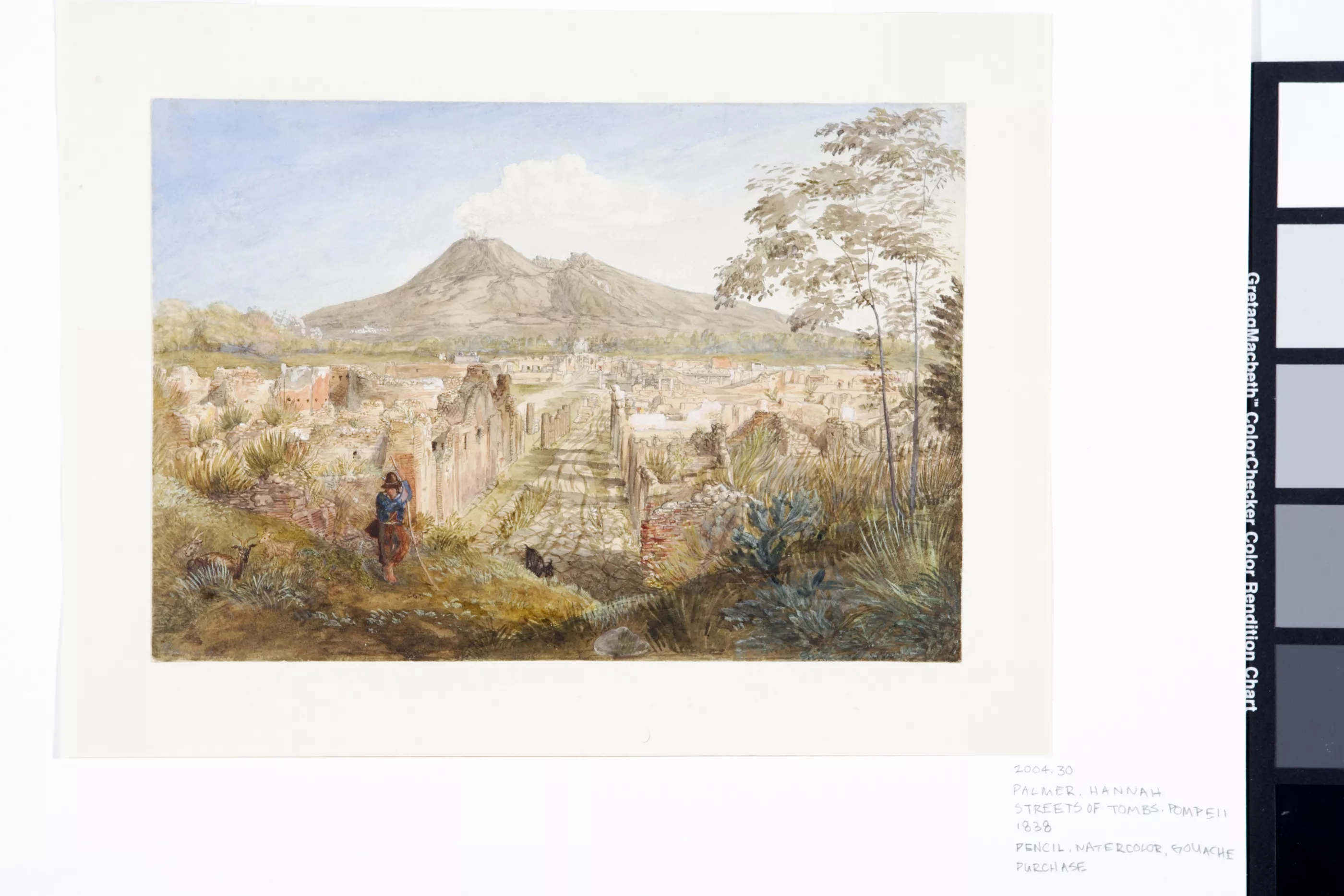

This painting depicts the Street of Tombs in Pompeii, Italy, with Mount Vesuvius in the background.

In 1837, Samuel and Hannah Palmer embarked on an extended honeymoon tour of southern Italy, a trip which Hannah’s mother, wife of the celebrated artist John Linnell, viewed as “little better than a madcap journey to the land of fever, volcanic catastrophes, banditti, priests, and (perhaps worst of all), of indigestible food” (Palmer 59). Mrs. Linnell’s remarks must be taken as at least somewhat tongue in cheek, since the Palmers’ trip was a middle-class version of the Grand Tour established by aristocratic northern European tourists in Italy more than 100 years earlier. That history is beyond the scope of this note, but for students of the Romantic period one relevant touchstone is the beginning of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ode to Naples”:

I stood within the City disinterred;

And heard the autumnal leaves like light footfalls

Of spirits passing through the streets; and heard

The Mountain's slumberous voice at intervals

Thrill through those roofless halls.

The Palmers arrived in Rome on November 14, 1837. In a letter to her parents dated the day of their arrival in the ancient city, Hannah writes that “tomorrow [I am] to begin the joyful business of colouring the Michael Angelos in the Sistine” (qtd. in Lister, Samuel Palmer 112). Hannah's father had commissioned her to make small, colored copies of Raphael’s Loggia, and to color and correct a set of his own prints depicting the frescos in the Sistine Chapel. Both Hannah and Samuel had works exhibited in Rome in 1838; however, none of the works were sold, and their titles remain unknown.

After spending six weeks in Naples, the Palmers traveled to Pompeii, where they stayed for several weeks. In early August, 1838, they arrived in Corpo di Cava, a small town about twenty-nine miles from Naples. From here they were able to observe a minor eruption of Mount Vesuvius. While in Pompeii, the Palmers stayed in one of the ancient buildings that had been occupied by a superintendent of the site. Although there is no direct reference to Hannah’s watercolor, her son, A.H. Palmer, wrote in 1892 that

[a]t Pompeii my father made many studies, and among them one of the amphitheatre, which is particularly pleasing work, and notable as showing a complete mastery of technical difficulties, besides great knowledge. My mother was equally industrious. (Palmer 70)

During the latter part of their honeymoon in 1837-38, Hannah Palmer and her husband Samuel, also a painter and a follower of William Blake, spent much time sketching at Pompeii. For this view, she chose a recently uncovered portion of the city. According to the archaeologist William Gell, “the greater portion of the Street of Tombs” was cleared in Spring 1813 under the “liberal patronage” of Napoleon’s sister Caroline Murat (v), who was Queen of Naples during the French occupation of 1808-1815. The larger ruin in the left foreground corresponds with the location of the Villa of Cicero, one of the first structures to be explored when Pompeii was rediscovered in 1748. Archaeological exactness was not Palmer’s primary concern, however, and the point of view—apparently from the top of the city’s eastern or Herculaneum Gate—seems improbable. The symbolic resonance of the Street of Tombs is more important, reminding the viewer that the whole city is a monument to the ancient Romans who perished in the eruption of 79 CE. Palmer’s composition foregrounds the sudden drop from the overlying ground to the depths of the formerly buried city, at the same time juxtaposing the fertile countryside with the destruction lurking beneath, as many similar pictures had done. Scores of paintings of Vesuvius were sold each year to tourists, whose general relationship to Pompeii in the early nineteenth century is ably illustrated by Chloe Chard in “Picnic at Pompeii.” The Palmers, belonging to an established subspecies of artistic tourists, hoped to sell some of their own paintings. Unlike their predecessors in the 1770s and 80s (such as Joseph Wright of Derby and Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun), the Palmers did not see a major eruption. Vesuvius had been quiet for four years, and Palmer’s painting is tranquil and orderly; the Street of Tomb runs vertically through the center of the picture plane, balanced by the horizontally spreading, light-filled ruins and cradled between the pastoral foreground and sleeping mountain.

Once a thriving Roman city, Pompeii was destroyed by the famous eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. Thousands of inhabitants were buried under sixty feet of scorching ash. The explosion took place over two days, but most victims were killed within minutes. Today the ruins are unearthed and attract millions of tourists annually. Molds of the dead and archaeological remains remind visitors of Mount Vesuvius’s destruction (Brilliant 292-96). It is worth noting in this context the remains of the ancient caldera (Mount Somma), clearly visible surrounding the cone of Vesuvius in Palmer’s painting. The eruption of 79 CE completed the destruction of this larger ancient volcanic cone, and provides the most imposing reminder of the catastrophe in Palmer’s peaceful picturesque rendering.

The excavation of Pompeii, which uncovered the majority of the city’s ruins between the years 1811 and 1824, provided nineteenth-century travelers with the opportunity to view antiquity in a highly preserved state. While other ruins only fueled more questions as to the reality of the past, the ruins of Pompeii offered its viewers detailed historical fact. Reflecting upon the unique status of Pompeii as ruins that remain somewhat intact, an article from Gentlemen’s Magazine in 1867 posits a direct link between the intrigue of Pompeii and the absence of similarly “complete” ruins in England:

No doubt the reflective reader, as he has traveled the several counties of England, has often wished, in various parts of England, that we could recall for a moment the ancient aspect of the country; reclothe the downs of Wiltshire with their native sward, and see them studded with tumuli and Druid temples, free and boundless as they extended a thousand years ago. (759)

The writer then goes on to link this desire to view England’s ancient past with the popular visual technologies of the era: “What exhibition could be found more interesting than a camera-obscura, which should reflect past incidents of historical or private interest, and recall with vividness and minuteness of life, at least the external characteristics of long past ages” (759). The ruins of Pompeii fulfill the role of that desired camera obscura, revealing an ancient past that the English longed to see in their own countryside.

The completeness of the ruins, however, does not preclude an impulse to imagine them in the era of their glory. Hannah Palmer’s Street of Tombs, Pompeii is an excellent example of the Romantic predilection for ruins, and demonstrates the era's interest in the ancient past more generally. Set in Italy, the painting also demonstrates the popular appeal of traveling to experience picturesque ruins firsthand. The painting further captures the evocative charm and nostalgia drawn from ruins, causing the viewer to imagine the glory they must have embodied in their original state and to feel a sublime connection to the past. This experience is sublime because of the limits placed on the viewer: because the ruins can only be physically experienced as the incomplete remnants of what they once were, the vision of their original, majestic grandeur depends entirely upon the imagination of the viewer. It is this invitation to envision and recreate the unknown past that charms and fascinates the tourist of ruins, and which made this particular aesthetic so popular during the Romantic period.

Locations Description

Classified as a stratovolcano (a volcano with a tall, multi-layered cone), Mount Vesuvius rises to 4,203 feet (1,281 meters). In recent centuries, Vesuvius’s height has diminished due to massive eruptions that have destroyed the volcano’s walls. The volcano’s location is in the Province of Naples near the city of Pompeii, which the 79 A.D. eruption infamously destroyed. Because it was covered in ash, the destructed city of Pompeii was preserved as a remarkable set of ruins. The site was rediscovered in the eighteenth century, and excavation efforts were made to discover the forgotten history and heritage of the submerged city (Brilliant 4-18). For a recent, interactive history, see the British Museum’s exhibition website for “Pompeii Live” (2013).

Accession Number

2004.30

Additional Information

Bibliography

“A Peep at Pompeii.” Chambers's Journal of Popular Literature, Science and Arts 300 (September 1869): 609-12. Print.

Brilliant, Richard. Pompeii AD 79: The Treasure of Rediscovery. New York: Potter, 1979. Print.

Chard, Chloe. “Picnic at Pompeii: Hyperbole in the Warm South.” Antiquity Recovered: The Legacy of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Ed. V. C. Gardner and J. L. Seydl. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2007. 115-32. Print.

Crouan, Katharine. John Linnell: A Centennial Exhibition, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge and Yale Center for British Art. New York: Cambridge UP, 1982. Print. Fitzwilliam Museum Publications.

Dix, William Giles. Pompeii and Other Poems. Boston: William D. Ticknor and Co., 1848.

Dryer, Thomas H. Pompeii: Its History, Buildings, and Antiquities. London, 1867. Print.

Gell, William, and John P. Gandy. Pompeiana: The Topography, Edifices, and Ornaments of Pompeii. Third ed. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1852. Print.

Grant, Maurice Harold. A Dictionary of British Landscape Painters: From the 16th century to the Early 20th Century. Leigh-on-Sea: F. Lewis, 1970. Print.

Harris, Judith. Pompeii: A Story of Rediscovery. New York: Tauris, 2007. Print.

Hayter, John. The Herculanean and Pompeian manuscripts. London, 1800. Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Web. 16 Aug. 2013.

Lister, Raymond. Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of Samuel Palmer. Cambridge UP, 1998. Print.

---. “Palmer, Samuel (1805–1881).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Online ed. Ed. Lawrence Goldman. May 2007. Web. 2 Apr. 2009.

---. Samuel Palmer: A Biography. London: Faber and Faber, 1974. Print.

---. Samuel Palmer and ‘The Ancients.’ Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1984. Print.

Malins, Edward Greenway. Samuel Palmer's Italian Honeymoon. London: Oxford UP, 1968. Print.

Mallalieu, Huon. The Dictionary of British Watercolour Artists up to 1920. 3rd ed. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2002. Print.

Palmer, A.H. The Life and Letters of Samuel Palmer, Painter and Etcher. 1892. Ed. Robert Lister and Kathleen Raine. London: Eric & Joan Stevens, 1972. Print.

Payne, Christiana. “Linnell, John (1792–1882).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Web. 20 Apr. 2009.

"Pompeii.” Gentleman's Magazine Dec. 1867: 759-69. Print.

“Pompeii.” Leisure Hour 79 (June 1853): 425-27. Print.

“Pompeii Live.” http://www.britishmuseum.org/whats_on/past_exhibitions/2013/pompeii_and_herculaneum/pompeii_live.aspx Web.

Sinfield, Ann. "Samuel Palmer Exhibition British Museum." Letter to Andrea Selbig. 3 Nov. 2004.

Starke, Mariana. Letters from Italy, between the Years 1792 and 1798, Containing a View of the Revolutions in that Country, from the Capture of Nice by the French Republic to the Expulsion of Pius VI. from the Ecclesiastical State . . . in Two Volumes. Vol 2. London, 1800. Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Web. 16 Aug. 2013.

Vaughan, William. Samuel Palmer, 1805-1881: Vision and Landscape. Burlington: Humphries, 2005. Print.

Ward, Gerald W.R., ed. Grove encyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Art. New York: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

Winckelmann, Johann Joachim. Letter and Report on the Discoveries at Herculaneum. Trans. Carol C. Mattusch. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2011.

Wood, Charles W. “The Ruins of Pompeii.” Argosy: a Magazine of Tales, Travels, Essays and Poems 38 (Dec. 1884): 459-67.